- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Religion

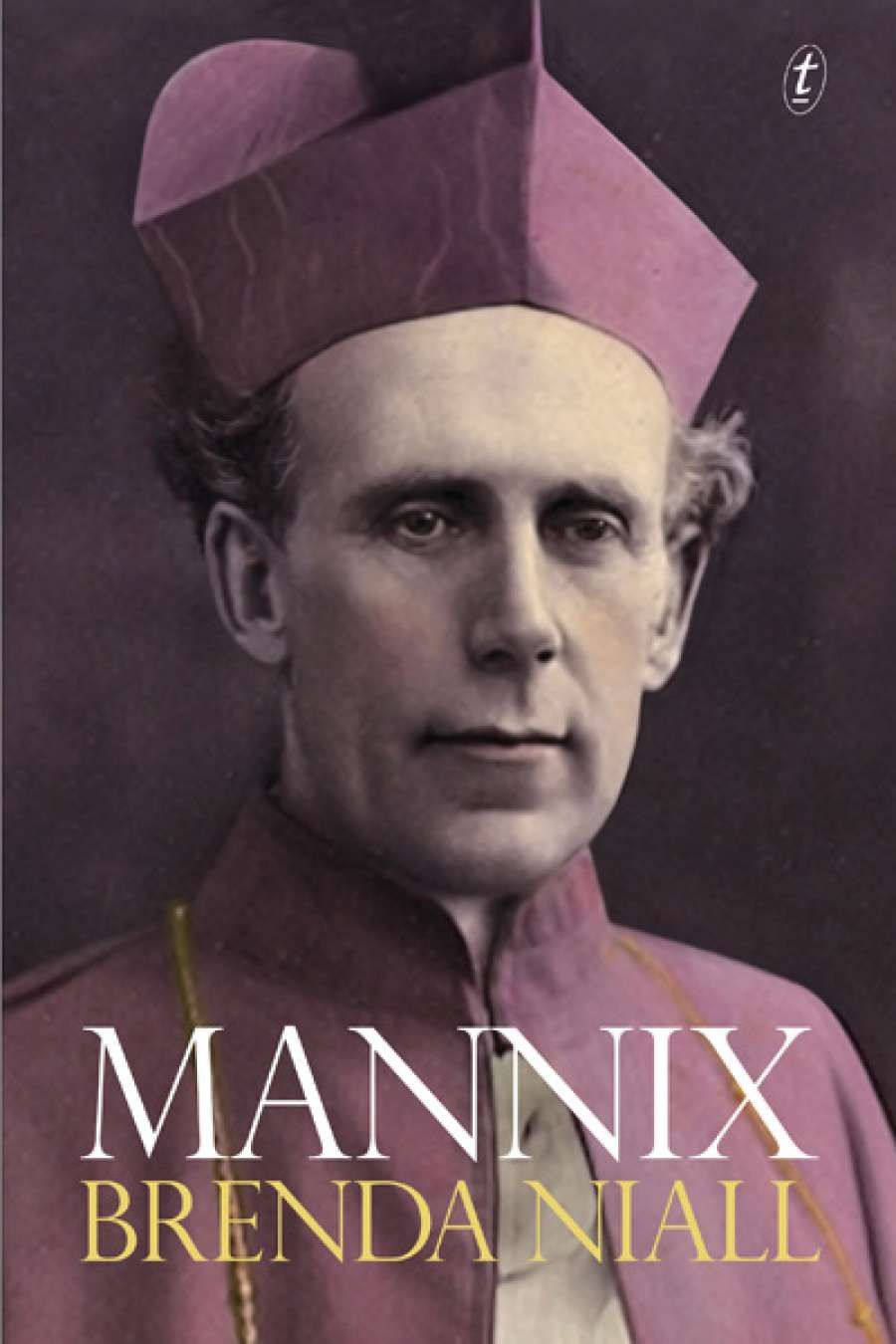

- Custom Article Title: Simon Caterson reviews 'Mannix' by Brenda Niall

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Book 1 Title: Mannix

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $50 hb, 464 pp, 9781922182111

Mannix aroused acrimony as well as reverence. A negative impression of Mannix’s unique and important place in history can perhaps be gained from what he was denied during his lifetime. His outspokenness was such that he was pointedly not made a cardinal. Indeed, in the 1930s Rome dispatched a papal delegate who was given the task of undermining the influence of Mannix and the other Irish prelates who led the Church in Australia at that time. Mannix had previously been ordered out to Australia from Ireland following the controversies that arose from the modernising influence he exerted as president of Maynooth, the leading Irish seminary.

The Mannix mystique was, Niall believes, a masterful performance. A ‘minimalist’ by nature, Mannix let as little as possible slip in word and gesture, and was adept at pausing for maximum rhetorical effect. One observer at Maynooth described him thus: ‘Tall, thin to emaciation, he looked as coldly aloof as one of El Greco’s Spanish Grandees.’

Attempting in 1920 to return from ecclesiastical exile in Australia, where he had been appointed Archbishop of Melbourne, Mannix was prevented by the British government from landing in Ireland as his presence on the island was considered inflammatory at a time of civil war. Indeed, so provocative was Mannix regarded on the issue of Irish nationalism that a British navy warship was dispatched to arrest him at sea.

If Mannix was obliged by the Church hierarchy to live in exile on the other side of the world, what was it that drew him so strongly back to Ireland? ‘As to the meaning of home for Daniel Mannix, who knows? A passionate love of Ireland, felt most in his Australian exile, and a romantic idealisation of life on the land, suggest that home meant a great deal.’

Archbishop Mannix walking to St Patrick's c.1954

Archbishop Mannix walking to St Patrick's c.1954

Mannix’s public persona might be seen as forbidding, yet as archbishop he was surprisingly open-minded in terms of his leadership style. Though ‘Mannix never learned how to share power’, he was a natural delegator, leaving the Catholic religious orders and parish priests within his diocese to run their own affairs, and promoting free speech among his clergy. ‘He once said that he never banned anything – and that was very nearly true,’ writes Niall.

At the same time, Niall argues, Mannix’s refusal to micro-manage diocesan affairs may not always have been the wisest approach, since, for example, in hindsight a closer supervision of the state of the clergy might have helped prevent subsequent crimes. ‘Mannix never had to face today’s realities of vocations in free fall and priestly training under the dark shadow of the clerical abuse scandal. He lived long enough to question clericalism and a triumphalist church but not to see their full cost.’

In nearly half a century as Archbishop of Melbourne, an extraordinary number of churches, schools, and hospitals were built, and Mannix worked hard to enfranchise Catholics in higher education and to encourage them to take an equal place in the wider Australian society. Niall quotes historian Patrick Morgan’s explanation of the immense respect that Mannix commanded among his flock being due to the fact that ‘[h]e identified with his people, speaking on their behalf to the public rather than blaming them, which made them warm to him’.

Mannix was a liberal thinker on a range of issues. ‘In his top hat and frock coat and his indifference to the telephone and the motor car, he presented himself as a man of the past but his thinking was advanced enough, in 1938, to insist on the need to make reparations to the Aborigines.’ Mannix also argued that traditional Aboriginal languages and culture should be preserved, and said that ‘sexual curiosity’ was natural and healthy.

During World War I, Mannix vigorously opposed military conscription, arguing that Australia’s exceptionally high rate of volunteerism and consequent disproportionately severe casualty rate were more than enough of a sacrifice. It is a stance that at the time attracted bitter charges of disloyalty and led to Mannix being labelled by one of his more hysterical detractors as ‘the Rasputin of Australia’. When Australia was threatened with invasion during World War II, Mannix did not oppose conscription, though he denounced the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima as immoral.

Mannix had no desire to engage in ecumenical dialogue with the Protestant denominations, though he was a friend of the Jews. Mannix, before World War II, championed the cause of Jewish refugees, supporting a proposal to establish a Jewish homeland in Western Australia. He reminded his people that Catholics and Jews were ‘all children of One Eternal Father’, and that Jesus Christ was a Jew.

Moreover, Mannix opposed the bipartisan White Australia policy, which prevented non-European immigration to Australia long before it was abolished by a centre-right Australian government in the mid-1960s. In the postwar years, Mannix took a major role in the anti-communist campaign within the Australian Labor Party; he supported a largely secret movement led by his protégé B.A. Santamaria that resulted in the ALP splitting disastrously and thus being rendered unelectable for many years. Mannix, meanwhile, succeeded in obtaining government funding for Catholic schools, pointing out that Catholics, like other taxpayers, were already helping to fund the state education system yet would prefer their own schools.

For someone who lived in the public eye for the best part of a century, and who at times during his career as a leading churchman attracted worldwide attention, Daniel Mannix was a private individual who did his best to erase the record of his inner life. Upon his death in Melbourne in 1963 at the age of ninety-nine, nearly all of Mannix’s papers were burned in accordance with his wishes. Brenda Niall begins her narrative with a description of this posthumous act of biographical self-obliteration. From the ashes of the bonfire of personal papers she creates a balanced and convincing account of Mannix’s life and times, neither hagiography nor its opposite.

Comments powered by CComment