- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

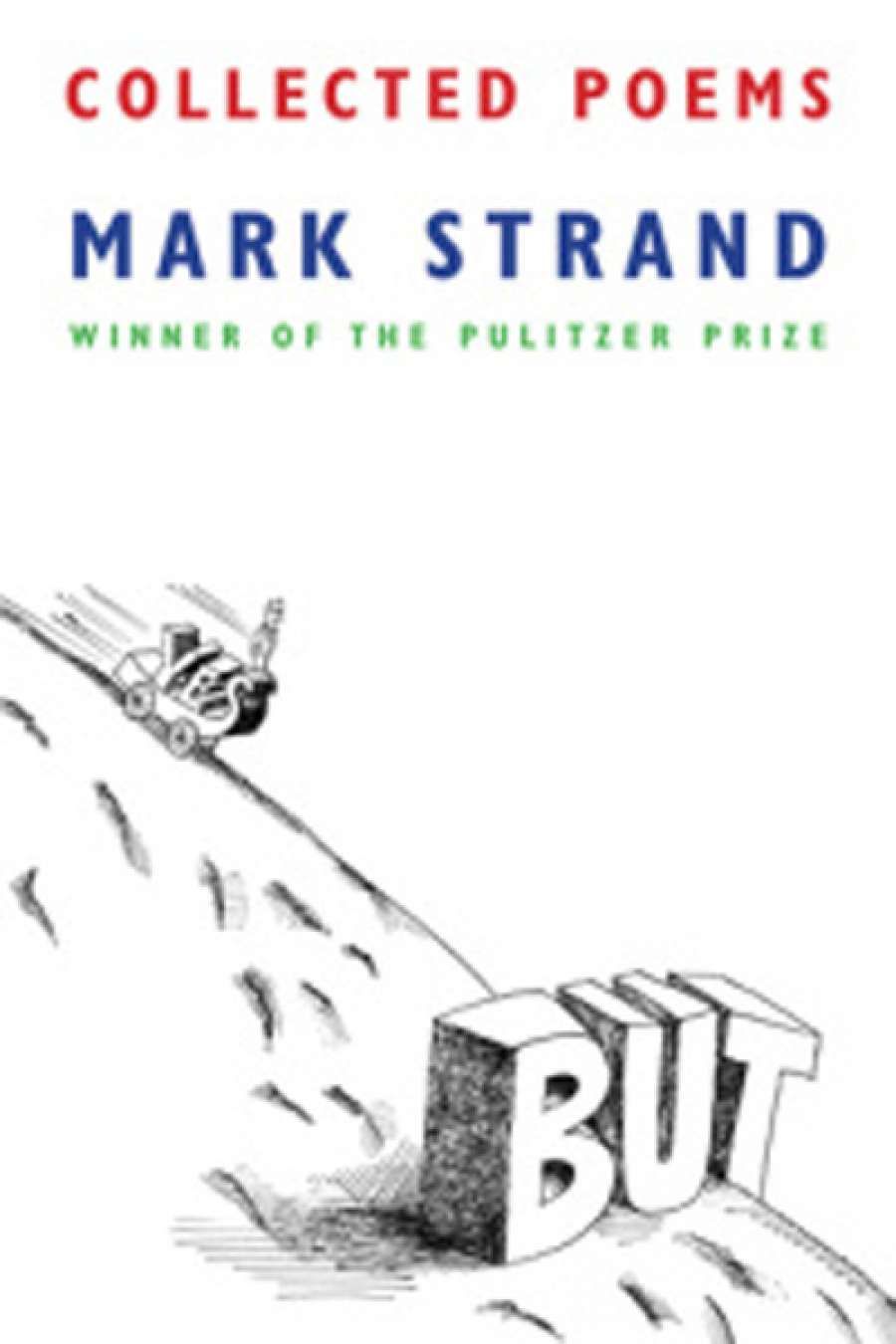

- Custom Article Title: Paul Kane reviews 'Collected Poems' by Mark Strand

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

It is tempting to say that when Mark Strand died last November American poetry lost one of its most distinctive voices. But it isn’t quite true. First, Strand had already retired from poetry several years earlier (before Philip Roth and Alice Munro caused a stir by doing so from fiction). Strand returned to his first career as an artist (a very talented one, according to his teachers at Yale’s Art and Architecture School), constructing a series of collages that were shown in galleries in New York. Second, Strand’s voice is of course very much present in the poems he leaves behind, collected in this handsome edition, which came out a month before he died. Though it is a voice of loss, it is not lost to us.

- Book 1 Title: Collected Poems

- Book 1 Biblio: Knopf, US$30 hb, 538 pp

Nor should it be lost on us. There is a haunting quality to Strand’s poetry that stays with you long after you put down his poems. It is difficult to characterise, or account for. The language is spare and yet gorgeous in effect; the imagery is repetitive (moon, stone, water, night, forest) yet fresh. The poems frequently cross the border into the surreal and yet stay close to our everyday experience. He is sombre and almost lugubrious at times, and yet frequently comic and ludic as well. He sets up a shimmering distance between the reader and the poem and yet no one is more intimate in manner and method. It is as if you can’t get at Strand directly; only through indirection can he be approached.

Perhaps, then, an anecdote is propitious, though it is literally telling tales out of school. It so happens that, as a tender sophomore at Yale in 1970, I had signed up for a poetry seminar with a new poet we were all crazy about. To be accepted into the class, you had to submit poems and undergo an interview. I showed up to my interview, which was in a small detached building on campus, and sat down before a tall, elegant figure seated behind a desk. ‘I’m sorry,’ said the man, ‘but Mark Strand couldn’t be here today and asked if I would conduct the interviews for him instead.’ Puzzled and not a little surprised, I finally stammered out, ‘But, but you are Mark Strand!’ With a sigh and a slight shake of his head, he replied, ‘I’m so tired of being Mark Strand.’

We, however, never tired of Mark Strand, and he went on to publish two dozen books and gather virtually all the prestigious prizes: among them the Pulitzer, the Bollingen, a MacArthur ‘genius award’, and a stint as poet laureate. But always in the poetry there was that weary sense of the precariousness of the self, of a nothingness at the heart of being – especially being ‘Mark Strand’ – that he nonetheless wrote into an imagined fullness. To revert to my anecdote: one day Strand brought to our poetry class his dear friend Elizabeth Bishop. They had met years before in Brazil and he was an admirer of her work at a time when she was not well known, except – in the words of James Merrill – as ‘the poet’s poet’s poet’. In introducing Bishop at a reading at the Guggenheim Museum in 1977, Strand said of her work: ‘It is the traveller’s destiny to suffer loss in order to keep going, and he keeps going even though the object of his quest is illusory.’ That remark strikes me as appropriate not only to Bishop but to a thematic strain in Strand’s work as well, one that was sounded early on in the iconic poem, ‘Keeping Things Whole’ (which, like Yeats’s ‘The Lake Isle of Innisfree,’ is the one poem most people know, if they know his work at all):

In a field

I am the absence

of field.

This is

always the case.

Wherever I am

I am what is missing.

When I walk

I part the air

and always

the air moves in

to fill the spaces

where my body’s been.

We all have reasons

for moving.

I move

to keep things whole.

‘Always in the poetry there was that weary sense of the precariousness of the self, of a nothingness at the heart of being’

Strand is a poet of the negativity of loss and absence. There is a staged or dramatised haplessness and helplessness (with hopelessness not far behind) in many of his poems. This is not Wordsworth’s ‘wise passiveness’ but rather the apprehension of what Strand’s master poet, Wallace Stevens, says of the listener at the end of ‘The Snow Man’: ‘And, nothing himself, beholds / Nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.’ The poems have a dreamlike atmosphere, as if they were whispered in our ear by a ghostly presence, and they carry all the disturbing inchoate meaningfulness that can inhabit our sleeping life. So adept is Strand at this that one gets the uneasy impression that only Mark Strand is awake in the world, as in ‘My Name’: ‘I lay in the grass, / feeling the great distances open above me, and wondered / what I would become and where I would find myself, / and though I barely existed, I felt for an instant / that the vast star-clustered sky was mine, and I heard / my name as if for the first time.’

Mark Strand (photograph by Sarah Shatz)

Mark Strand (photograph by Sarah Shatz)

Not since Emily Dickinson has a poet written so often, and so well, of an imagined transition to the afterlife. Much of Strand’s late verse is posthumous before the fact. He has peopled nothingness to give it a shape, a discernment that he proceeds to undo by undercutting it. By nature unreligious – or rather, unbelieving – Strand can deploy religious tropes and concepts with a freedom that re-imagines them in a new register, one that seems, oddly enough, wholly believable. In particular, one of his late poems, ‘Poem After the Last Seven Words’ (a meditation on Christ), is so profoundly religious that only a non-believer could have written it: perfectly balanced and modulated, any hint of piety would have ruined the effect.

In literary terms, Strand is often placed in the company of poets who were friends of his: W.S. Merwin, Galway Kinnell, John Ashbery, Charles Simić, Richard Howard, Charles Wright, Joseph Brodsky and – much younger – Jorie Graham, all of whom have a kind of celebrity status in the United States, though no one carried it off with more aplomb than Strand (even as he mocked his own suave urbanity in his poetry).

Strand’s style was set early on in Sleeping with One Eye Open (1964) and, though it went through stages over the next five books, it remained identifiably his voice throughout. The only radical change occurred in his Selected Poems (1980), where he included new work that, though accomplished and intriguingly autobiographical, marked a dead end for him. He didn’t fully believe in those poems and stopped writing poetry for almost a decade. When he returned to it, with the publication of The Continuous Life in 1990, there was again the old manner but with a new freedom and range. It marked a turning point in his career. Three years later, he brought out a long poem in forty-five sections in triplets, Dark Harbor, which is surely among the great sequences in American poetry, ravishing in its beauty and assurance. It showed Strand at the height of his powers. (His Elegy for my Father, from 1973, is his other magnificent long poem.) Strand’s next book, Blizzard of One (1998), brought him the Pulitzer Prize, and contains what some feel is his best poem, ‘The Delirium Waltz’, which is breathtaking in its ecstatic movement and surreal swing. After Man and Camel (2006), he retired from writing poems, though the short prose of Almost Invisible (2012) is included in Collected Poems as prose poems (even if Strand did not consider them as such at the time).

As a poet, Strand is best read not poem by poem but book by book: the individual poems can be astonishing, but his effect is accumulative and works over time. Time is Strand’s grand theme, and now that he’s gone, the poems will be finding their own way in time without him.

Comments powered by CComment