- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Custom Article Title: Peter Hill reviews 'Order and Variation' by Kirsty Grant

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

It was the great American Conceptual artist Sol LeWitt who organised Melbourne artist Robert Jacks’s first show in Manhattan. This was held at the New York Cultural Centre in 1971, part of a program where each exhibited artist nominated his successor. Jacks had been enjoying a stellar rise since his début solo exhibition at Gallery A in Melbourne in 1966, when he was twenty-three years old. All twenty-five abstract paintings in that show sold. Each one had a title referencing James Joyce’s Ulysses, such as Mr Bloom with his stick gently vexed (1965). The largest, Timbrel and harp soothe (1965), was bought by the National Gallery of Victoria even before the show opened.

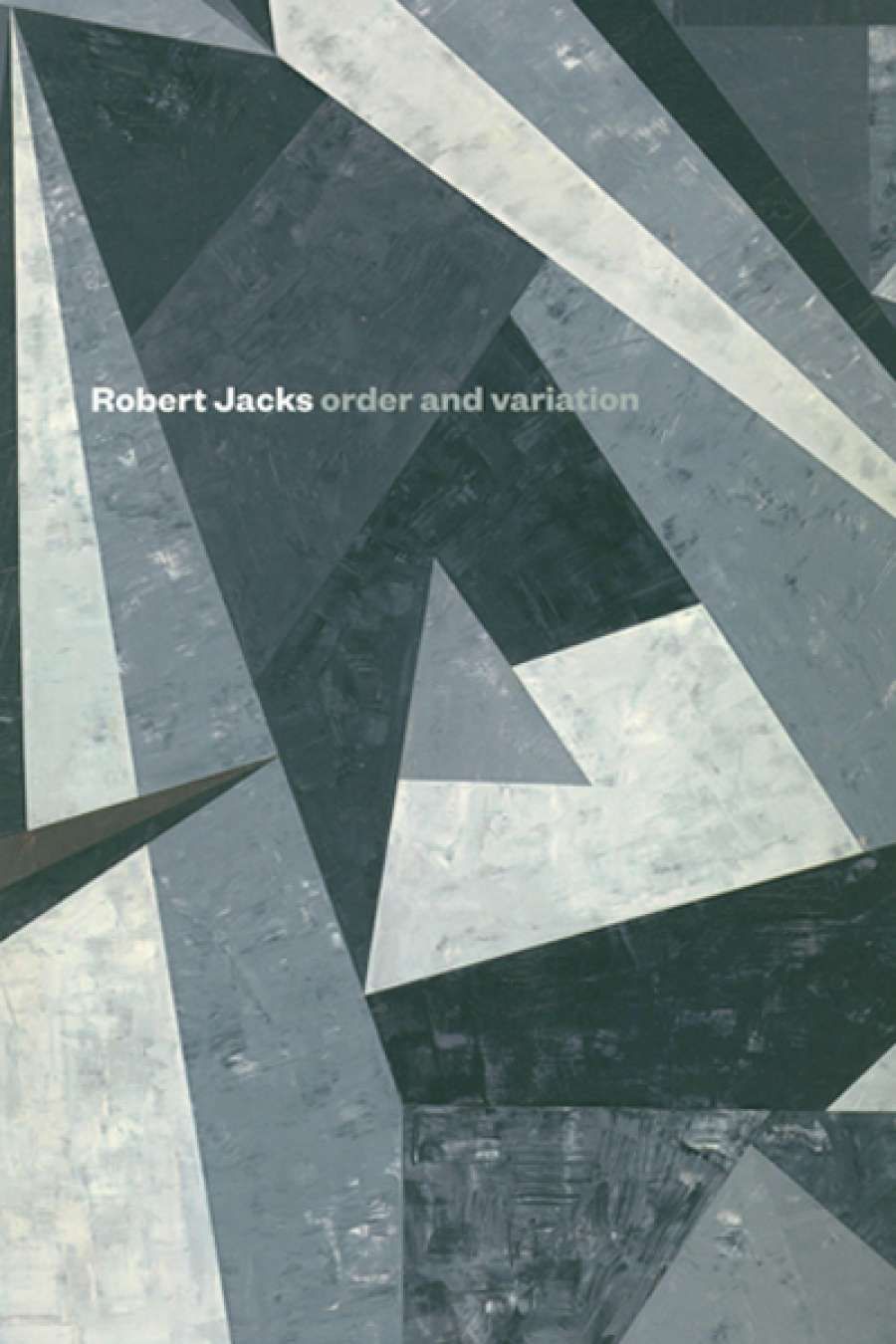

- Book 1 Title: Order and Variation

- Book 1 Subtitle: Robert Jacks

- Book 1 Biblio: National Gallery of Victoria, $29.95 pb, 195 pp

These and other anecdotes emerge throughout the wonderfully produced book that accompanies the artist’s comprehensive exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria. It is written by Kirsty Grant (formerly with the NGV and now the director of the Heide Museum), with additional essays by Beckett Rozentals and Peter Anderson. Jacks was collaborating on all aspects of the show when he died in August 2014, shortly before the opening. He would have been elated by the hang and by the publication.

Jacks was legendary for his generosity towards young artists and his students. One friend told me about the time Jacks went to a Robert Rauschenberg opening and ended up back at the after-party in Rauschenberg’s three-storey factory block. On the ground floor guests mingled and looked at the works on the wall. On the second floor Andy Warhol held court. But it was the live music from the top floor that drew Jacks: The Velvet Underground was playing at one end of the studio.

This fascinating book contains many unfamiliar anecdotes, such as the one about Jacks being bullied at school and his mother sent him to boxing lessons so he could better defend himself; or how his father, who was serving overseas in World War II when Jacks was born, became curator of the Burnley Parks and Gardens and the family lived on-site in ‘The Lodge’, down by the Yarra River. ‘The house was attached to the garden nursery,’ Beckett Rozentals writes, ‘and Jacks had his introduction to drawing there, sketching plants with his father. His mother, Jean Elizabeth (Betty), and Jacks Sr attended many flower and garden shows, and the orderly rows of flowers Jacks saw on these excursions … later influenced the way he ordered his sculptures in rows in his own studio.’

Robert Jacks in his studio, 1983

Robert Jacks in his studio, 1983

At Richmond Technical College, Jacks began a lifelong friendship with fellow student Jan Senbergs. We follow Jacks’s journey from there to Prahran Technical College to RMIT. As a student there, in 1961, Jacks enlisted in a student exchange program with East Sydney Technical College and ‘in the middle of a very grim winter stood on the steps of Flinders Street Station with a placard reading “John Firth Smith” … and Jacks’s circle widened as he began socialising with his Sydney contemporaries’.

Ideas spread in all sorts of ways; we don’t need the fashionable term ‘meme’ to tell us that. Several times a day, emails from the visual arts site e-flux at 311 East Broadway, New York, arrive with press releases about new art from around the globe – Stockholm, Glasgow, Shanghai, Mexico City. Back in the 1960s, if you lived in Melbourne, Dublin, or Bangkok, you constructed a Cubist-like view of the art world, assembling images and ideas through a mix of guesswork, chance encounters, passing exhibitions, and for those who could afford it, travel. Rozentals writes: ‘At this time Jacks and many of his contemporaries, including Janet Dawson, Dale Hickey, Robert Hunter and John Peart, moved towards a new style of abstraction broadly referred to as “Colour Field” or “hard-edge” painting which originated in the United States. While these artists had seen this style in magazines and exhibition catalogues, Jacks’s first introduction to it came from James Doolin, an American artist who, after completing his studies at the Philadelphia School of Art, lived in Australia from 1965 to 1967. In 1967 the NGV mounted Two Decades of American Painting, the first large-scale exhibition in Australia to survey contemporary American art, which exposed Jacks to galleries full of this new style of abstraction, by artists such as Josef Albers and Ad Reinhardt. This exhibition and Jacks’s friendship with Doolan had a profound influence on his move towards more reductive, minimal works.’

In the late 1960s, Robert Jacks went to New York to contribute his own unique synthesis of the then current hard-edge abstractionists and a trail of reductionism that leads back to Matisse. By 1971, when he first showed in New York – and before moving to Texas and another equally important formative period – the art world was already at least four years in to a new kind of art labelled ‘Conceptual’ and heralded by works such as Joseph Kosuth’s One and Three Chairs (1965). Painterly debate in bars like Fanelli’s continued in a milieu that included overlapping tendencies and movements from Pop Art to monochromatic minimalism. Jacks’s work reflected all this, especially in his serial artist books, and his sculptures, beautifully presented in the exhibition and the catalogue. It is highly recommended.

Comments powered by CComment