- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

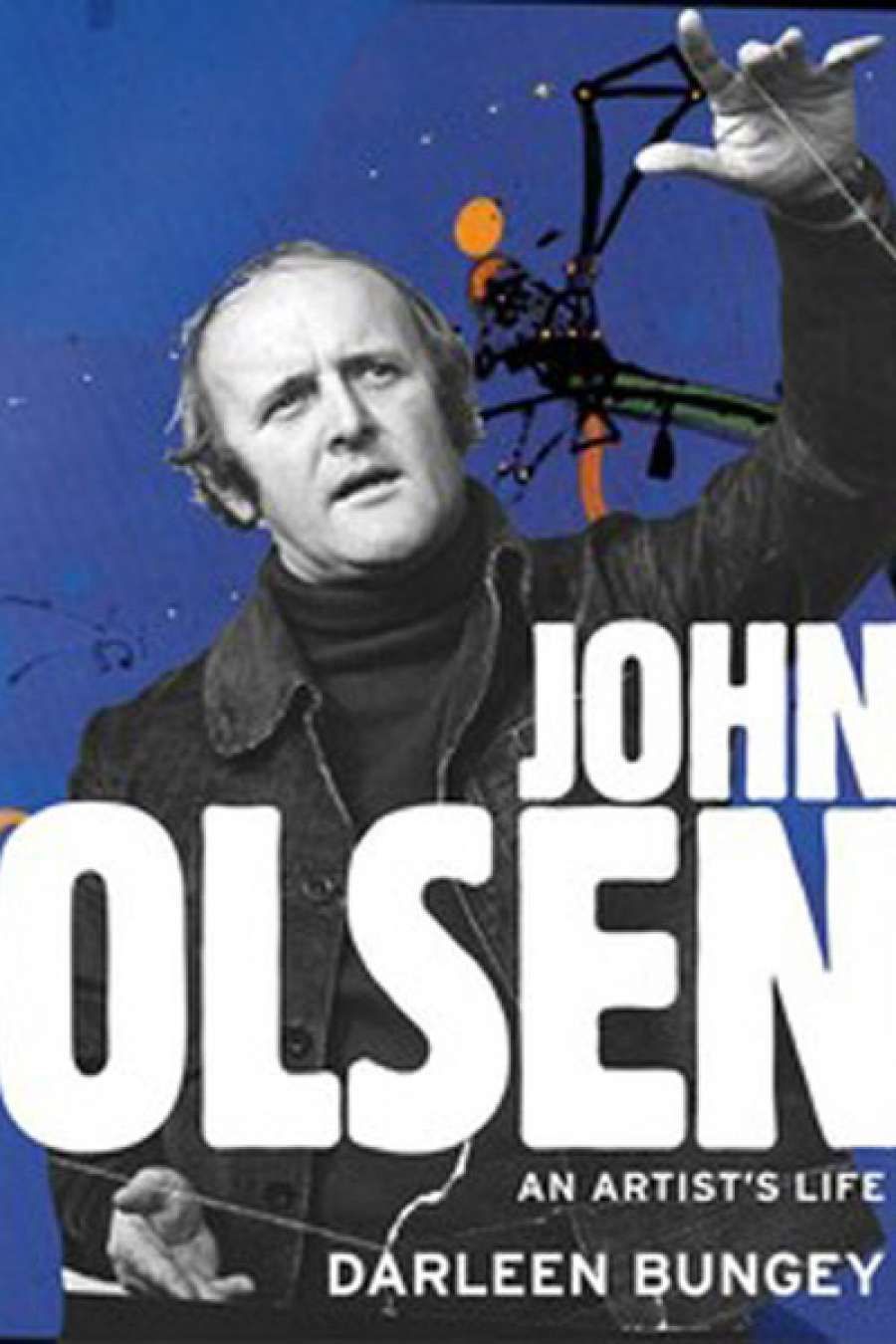

- Custom Article Title: Patrick McCaughey reviews 'John Olsen' by Darleen Bungey

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Eight years ago Darleen Bungey published a revelatory biography of Arthur Boyd. She cast shadows across the ‘idyllic’ Open Country years where the extended Boyd family lived in suburban Murrumbeena and unflinchingly detailed his declining, alcoholic years at Bundanon. Bungey’s compelling new biography of John Olsen has its share of revelations. Olsen’s weak and inadequate father wound up destitute on the streets of Sydney, largely sustained by handouts from his son. Boyd was an intensely private man, friendly but reclusive. Olsen has been a public figure for most of his long career, reaching back to the early 1950s when he emerged from the Julian Ashton school as the star student of the difficult and demanding John Passmore. Boyd was dead before Bungey published her biography. John Olsen, happily, remains a boisterous octogenarian, going strong in art and life. A living subject is not always to the biographer’s advantage. Bungey can sound like a cheerleader: ‘Like Jay Gatsby, John was a man from an impoverished childhood with a mind for enquiry, a hunger for romance and a need for invention.’

- Book 1 Title: John Olsen

- Book 1 Subtitle: An artist's life

- Book 1 Biblio: ABC Books, $59.99 hb, 516 pp

Olsen was acknowledged as the leading artist of his generation in Sydney throughout the 1960s. ‘Captain Olsen’ Leonard French dubbed him, ironically, but not without affection or admiration. One of his early lovers, Diana Stearns, saw that ‘he needed to become somebody, to be famous’. Olsen embraced the role and acted it out. Bungey quotes Lily Brett’s shrewd assessment: ‘you are never given to see Olsen being Ordinary … it’s as though he can only bear to be seen on form.’

In 1960 Olsen painted the breakthrough Spanish Encounter, which shook Sydney painting from genteel Francophilia into the raw edge of contemporary art. Painted in five hours during an all-night stand after a furious row with Stearns, Olsen roused a dazed William Rose to help him get the three large panels down from his attic studio in Victoria Street and carry them round to the Terry Clune Gallery. The Art Gallery of New South Wales bought the painting at first sight, and it has been rarely off its walls ever since.

The Journey into You Beaut Country series followed hard upon this success. Their energy, drive, and originality dazzled with the bonding of landscape and cityscape. Even the National Gallery of Victoria, always the last to catch on in those days, bought a painting from the group. Olsen reached the zenith of his early fame in the mid-1960s with his explosive ceilings for fashionable collectors and decoratively attractive tapestries. The latter took Olsen and his young family to Europe in 1966, settling eventually in Castelo de Vide in Portugal, close to the celebrated Manufactura de Tapeçarias de Portalegre, but not before a devastating car crash severely injured Olsen, his wife, Valerie, and their two small children, Timothy and Louise. Olsen admitted ‘glimpsing into the corridors of death’. Bungey handles this part of the narrative well and conveys the restorative power of the Iberian Peninsula on Olsen’s art and imagination.

Spanish Encounter by John Olsen, 1960 (Art Gallery of New South Wales)

Spanish Encounter by John Olsen, 1960 (Art Gallery of New South Wales)

Even at the top of his form and fame, money was a concern for Olsen. Frank McDonald, his new dealer, promised him, perhaps over-generously, a monthly stipend of £200. Towards the end of the year payments became erratic. Olsen grew increasingly anxious about his family’s security and return to Australia. McDonald, at the last minute, provided ‘a hefty 1500 pounds’, and the Olsens returned to Sydney.

Money issues led him to open the Bakery School in 1967. By all accounts he was an electric teacher and the role played to the showman side of his personality. But it distracted him from his work. Precipitously, he dropped the Bakery School and decamped to Melbourne in 1969. He landed improbably in the artists’ colony presided over by Clifton Pugh, the erstwhile and earnest Antipodean, at Dunmoochin at Cottles Bridge just outside Melbourne. After their home in Watsons Bay on the Harbour, their initial accommodation was uncomfortable and cheerless, and the atmosphere was fraught. Tim Olsen, then aged seven, was bullied by the local toughs and had the disturbing experience of catching Pugh fucking a model on his front lawn. But Olsen’s art, away from ‘the rat race of the Siren City’, renewed itself. He produced a series of landscapes of a strong lyrical beauty, including such central masterpieces as Pied Beauty (Art Gallery of South Australia).

The Sydney Olsen returned to in 1971 was a changed place. Brett Whiteley, summarily expelled from Fiji, had arrived home in 1969 in a blaze of klieg lights and subfusc scandal. He quickly became king of the heap. Olsen felt he had been thrown away ‘like an old boot’. The 1970s was a difficult decade for Olsen, now in his forties: it was ‘marked by a steady drip of unhappiness’, in Bungey’s icy phrase. His marriage to Valerie began to fray. They made an unwanted move from Watsons Bay to a new and unsatisfactory home in Dural without a proper studio. One year he failed to paint a single oil painting and had to satisfy himself ‘painting watercolours on the bonnet of his car’. A nasty undercurrent of critical gossip in the 1970s insinuated that Olsen was ‘yesterday’s man’, that he had ‘had his day’.’

The gossip was as malicious as it was ignorant. Olsen in the 1970s produced his magical and magisterial mural for the Sydney Opera House, A Salute to Five Bells and the first of his major paintings on inland Australia, notably Lake Eyre in flood. The mural in the north foyer of the main concert hall faces the Harbour and draws its inspiration from Kenneth Slessor’s eponymous poem, a threnody recalling the accidental drowning of a friend who fell from a ferry. To make a nocturne on that scale – the mural is over twenty-one metres in length – is boldness itself. The foyer is used principally in the evening and Olsen seized the opportunity to let his art meet and match the shifting lights and movements of the Harbour at night. Jeered at by the riggers and labourers when he was installing it, A Salute to Five Bells still earns only grudging admiration from those who ought to know better. Hard to reproduce, the work is not helped by a wood coping above it and an intrusive guardrail before it. Its beauty and its daring are not to be denied as Australia’s largest and finest colour field painting.

Counterpointing Bungey’s progress of the artist, a second narrative of John Olsen and his women pushes itself on the reader. Married four times and with numerous liaisons, both long-term and brief, Olsen comes across as both uxorious and a serial adulterer. Bungey describes his first marriage to Mary Flower, ‘forthright, engaging and unconventional’, a niece of the painter, Cedric Flower and familiar with bohemian Sydney, as a ‘revolving door with a restless, unhappy husband moving out, then moving back’. One day Mary caught him unaware in his studio. ‘Go away, go away,’ Olsen shouted, so Mary replied: ‘Come out, come out. I know you’re in there shagging the parish priest from Ipswich!’

Of his second marriage to Valerie Strong, herself an artist, Bungey steelily notes that ‘to keep his family together, he lied to his wife’. He knew ‘Valerie deserved better’ and dwelt in the false assurance ‘that I would always go back to her’. Until Noela Hjorth, an ambitious printmaker came along.

When asked ‘Was it a passionate relationship with Noela?’ John’s reply is swift: ‘It’s described as sex.’ When questioned further: ‘Was it in capital letters?’ He replies: ‘In neon lights as well.’ Their marriage devastated Olsen’s family. In 1981, Olsen and Hjorth settled in Clarendon, an attractive village just north of Adelaide. Here Olsen painted some of the finest work of his mid-career, but the Art Gallery of South Australia, according to Bungey, shunned him. Within a year of the marriage, Olsen confided to his diary: ‘Personal life quite miserable. How much can I endure?’ Nordic earth goddesses can be wearing company and quite hapless when it comes to the washing up. ‘The end was sealed,’ in Bungey’s account, ‘on the evening Noela bounded into his studio, interrupting his work, to demand: Where’s my dinner?’

All that nomadic inconstancy took its toll on Olsen’s persona. Yet it seems incredible that he had to wait until 1986 when he was fifty-eight to have his first museum survey, not at the Art Gallery of New South Wales but by the persistent Maudie Palmer at Heide. Rightly, it was received triumphantly and paved the way for his canonical status in Australian painting. Years earlier, he had longed for the stability of fidelity – ‘no more women, no more lies’. He would find it with Katharine Howard, his wife of the past two decades.

Comments powered by CComment