- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

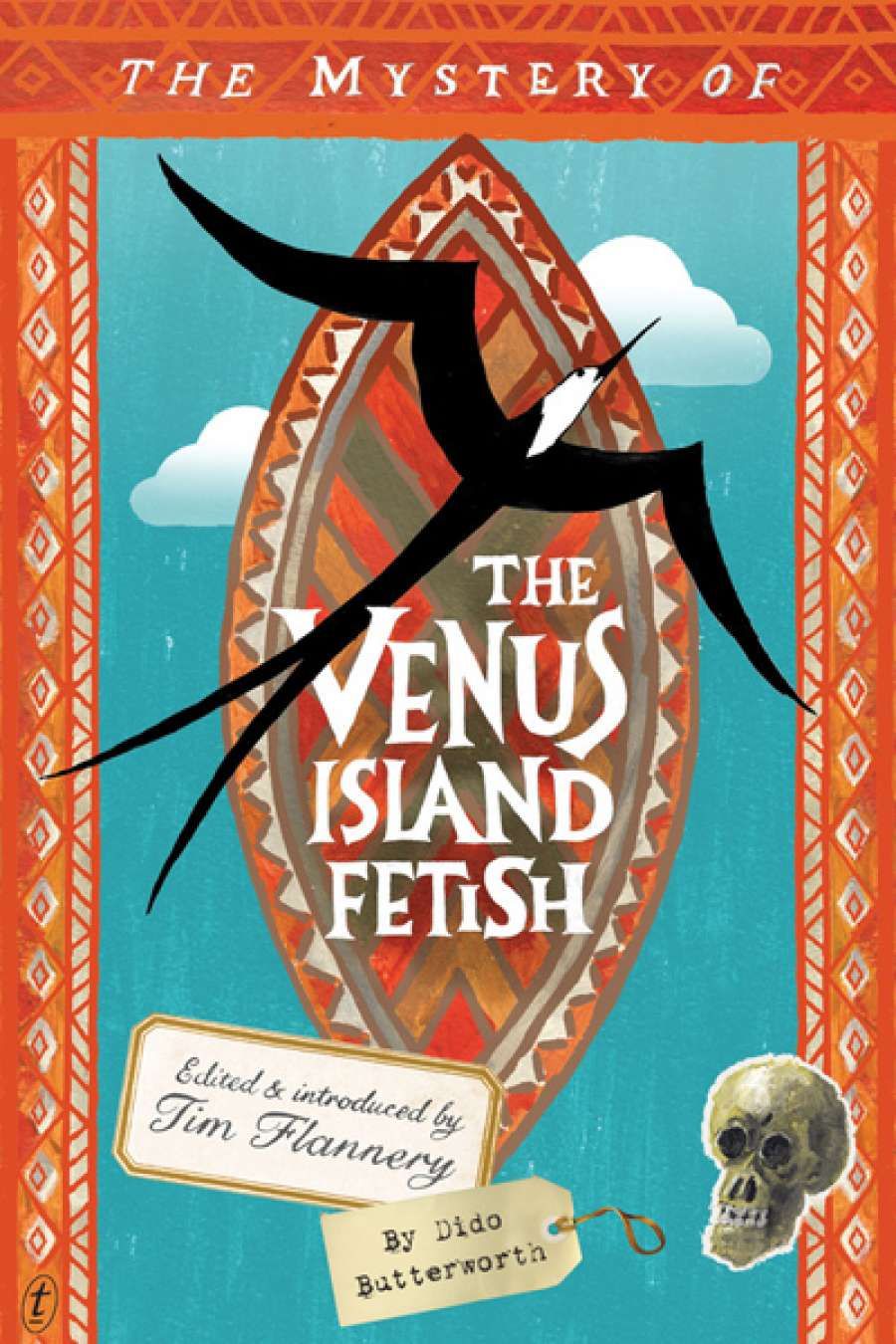

- Custom Article Title: Fiona Gruber reviews 'The Mystery of the Venus Island Fetish' by Dido Butterworth (Tim Flannery)

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

It is 1932 and as the SS Mokambo steams into Sydney Harbour with Archie Meek on board, the Australian Museum’s young anthropologist is about to discover that he has committed a terrible faux pas. After five years away in the Venus islands studying the customs and culture of its head-hunting inhabitants, Meek is eager to be reunited with Beatrice Goodenough, the beautiful but sheltered registrar of the museum’s anthropology department. In true island fashion, Meek has accompanied his request for her hand in marriage with the sincerest love token a man can proffer. Unfortunately, on receipt of his dried foreskin, lovingly posted, Goodenough fails to respond as a Venus Island maiden would. A younger, weedier Meek might have been ready to crumple at such rejection, but the hesitant stripling of nineteen is now a bronzed hunk of twenty-four, ready to claim Beatrice as his own despite the misfiring of his culturally specific courtship ritual.

- Book 1 Title: The Mystery of the Venus Island Fetish

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $29.99 pb, 283 pp

If Meek has changed dramatically, so too has Sydney and its museum.

The city is full of beggars and urchins, and is in the grip of what everyone is calling the ‘crash’. Equally alarmingly, in the hallowed galleries full of dangling skeletons and dioramas the ranks of Meek’s erstwhile colleagues have started to thin.

The museum’s handsome and debonair director, Vere Griffin, is acting strangely. Worst of all, the Venus Island Fetish, a fearsome mask surrounded by thirty two human skulls and an aura of terrible magic, seems to be sporting a different set of bony trophies. Could there be a connection between the missing curators and the new-looking heads?

Meek won’t relax until he has solved this and other mysteries, while down at the Maori’s Head, the Wooloomooloo watering hole for the museum staff, rumours are rife. Was the curator of archaeology bumped off? Who is drinking the pickling alcohol? What does the museum’s chief taxidermist hide in his house? Why are the museum’s accounts under scrutiny? What does Griffin plan to exchange for a consignment of rare stuffed goats from the Vatican Museum?

Inevitably, the stiff-collared, Empire-hued mischief in Tim Flannery’s sleuthing caper also encompasses the philosophy of white (preferably English-speaking and Anglican) superiority at the apex of the cultural pyramid, with a descent down the slopes to the hunter-gatherers languishing at the bottom. Archie might feel his greatest teachers have all been Venusians, but this is a minority view.

The museum sports a skeleton of the last ‘Tasmanian Aboriginal’, and an awful lot of human remains collected from around Australia have small round holes in them and show signs of burning. It is only when Archie’s colleague, Courteney Dithers, the Curator of Mammals, visits Abotomy Hall, the remote estate of nouveau-riche collector and museum board member Chumley Abotomy, that the full horror of species’ collection becomes plain. The battué, a shooting drive of every animal on the estate, reveals a bloodthirsty mindset that is wholesale in its destructiveness. ‘If it wasn’t for do-gooders like you we’d have finished off the lot of them long ago,’ boasts Chumley, including rare marsupials and Aboriginals in his sweeping vision of land improvement.

This is Tim Flannery’s first venture into fiction. The author of The Future Eaters (1994) and The Weather Makers (2005) lets rip with a brilliantly daft romp that, alongside a predilection for suggestive surnames, mines the mindsets and manners of pre-war Australia to perfection. The cultural cringe looms large with its worship of Oxbridge scholars and anyone with a title. It also encompasses the idea that nothing born or made in Australia can rival that which has the fortune to spring from elsewhere and has its apotheosis in the director’s secret worship of various items of Meissen china.

‘Tim Flannery lets rip with a brilliantly daft romp that, alongside a predilection for suggestive surnames, mines the mindsets and manners of pre-war Australia to perfection’

Flannery is sharp in his evocation of Depression Sydney, its slums and street life, where the ‘Loo’, as Wooloomooloo was known, was a place of vice and danger and no trees or landscaping softened the city’s asphalt and tram wires. Flannery’s research is deftly transmitted. His conceit, in a slightly long-winded introduction, is that he is not the author and that the manuscript was discovered hidden up the rectum of a taxidermised baboon. Its purported creator, 1930s curator Dido Butterworth, turns out to be a pseudonym for yet another curator, annelida expert Hans Schmetterling. Flannery’s editorial duties, he tells us, have been light except for the removal of ‘numerous (and often tediously lengthy) descriptions of worms’.

In fact, Flannery’s credentials, alongside those of environmentalist and global warming activist have involved lengthy stints in academia, including posts as director of the South Australian Museum and chief research scientist at the Australian Museum. The latter establishment, founded in 1827, is still a treasure house of natural history and anthropological artefacts and a bastion of scholarship. Its cultural values may have radically changed and the style of curatorship definitely has, but the nineteenth-century roots of the great museum collections still remain beneath the modern face of interactive displays and an appreciation of cultural diversity that eschews hierarchies. It is also a fabulous setting for an amateur detective series. Is this the start of a swathe of Meek mysteries, featuring our innocent but plucky hero among the world’s great collections and teaming cultures? Flannery may have tossed this off as a stand-alone caprice, but I for one hope that we see much more of the redoubtable Archie Meek.

Comments powered by CComment