- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

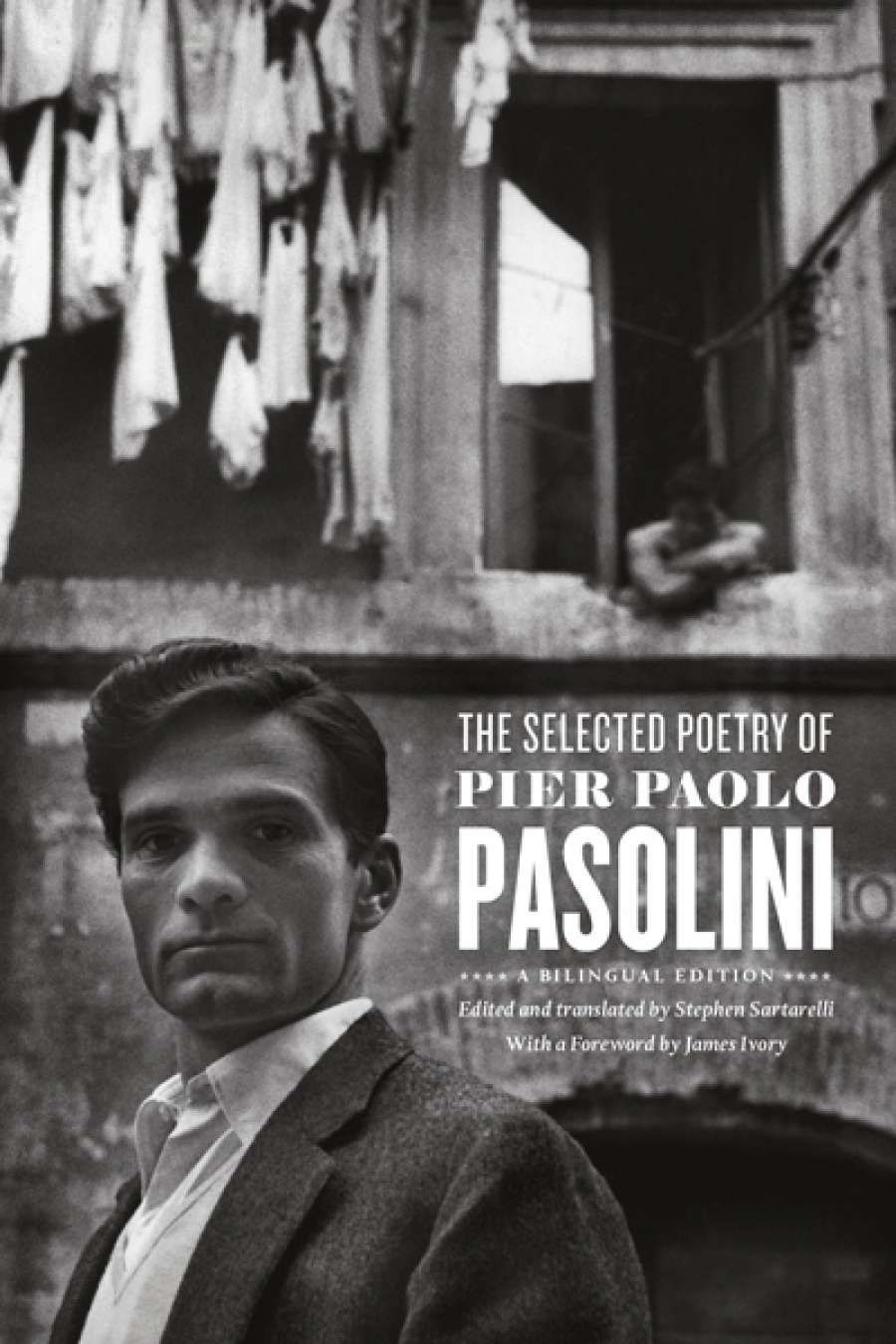

- Custom Article Title: Annamaria Pagliaro reviews 'The Selected Poetry of Pier Paolo Pasolini' edited and translated by Stephen Sartarelli

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Book 1 Title: The Selected Poetry of Pier Paolo Pasolini: A Bilingual Edition

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Chicago Press (Footprint), $77 hb, 456 pp, 9780226648446

Pasolini, already established as an engaged polemicist, came to cinema, with little training in 1961, because, as he himself affirmed, its language was ‘transnational’ and ‘transclass’. He was already an established poet, novelist, and political and literary essayist, whose work had been both acclaimed and condemned. Controversy, scandal, and provocation both shaped and tormented his life and career.

Pasolini considered himself and was, above all, a poet. The influence of poetry, as many critics have noted, pervaded his oeuvre. For this reason, Sartarelli’s excellent translation of selected poems will be welcomed as a major contribution to understanding the breadth of his artistic vision and as a key to the reading of his films.

‘Pasolini considered himself and was, above all, a poet’

Although the focus must be on the brilliant English rendition of Pasolini’s poems, collected here in a thoughtful and representative selection from the nine books of poetry, of equal note is Sartarelli’s lengthy four-part introduction, which offers an acute scholarly overview of the artist’s oeuvre and engages with the complex critical discourse on Pasolini the person and his work.

Sartarelli follows Pasolini’s poetic and ideological journey, placing him in a European post-symbolist context, as well as within the classical Italian literary tradition. Pasolini’s dialectical approach to language – his contrasting use of Italian with his personalised form of Friulian dialect – is used as a guiding theme for the examination of his different collections. He defines the poet’s use of dialect in his first volume (La meglio gioventù, 1954) as both a political act, partly against the fascist imposition of standardised Italian, but also as symbolically representing the lyrical language of youth; of a timeless agrarian community, of mystical innocence and vitality, while Italian came to embody the opposite, the language of maturity, of modern institutionalised society, of corruption and death, the language with which to vent his furore as a civic poet, particularly in his most famous collection, Gramsci’s Ashes (1957), and his left-wing politics. The poem ‘Language’, from The Nightingale of the Catholic Church (1958), best expresses the poet’s ambivalence towards Italian. It is the language which attracts him in its expression of tradition and beauty, but repels him as the medium of authority and convention. Here, Sartarelli locates Pasolini’s break with Italian Hermetic formalism, which shunned psychology and subjectivism. Using instead his very personal and allusive voice, Pasolini openly declares his ‘sins’ – homosexuality and fascination with the language of tradition.

‘Pasolini is frequently characterised as placing himself polemically in a position just out of synchrony with contemporary trends’

Pasolini is frequently characterised as placing himself polemically in a position just out of synchrony with contemporary trends, criticising Hermeticism when it dominates the literary scene and espousing it in a particularly subversive way when its influence wanes. Similarly, with Neorealism, he elevates the represented reality to the level of myth. His use of language is best described as highly experimental, a fluid plurilingüismo or multilingualism. Sartarelli constructs an image of Pasolini the artist as one who felt deeply his contradictions and underscores the sincerity which Pasolini brought to his writing; a confronting sincerity which led to his violent and untimely death in 1975. Refuting any fatalistic hypothesis positing Pasolini’s death as something wished for, or even staged by, the poet himself, Sartarelli insists that a large body of research shows that it was murder, in a period characterised by violence and terrorist activity.

Pasolini’s Collected Poems was finally published in 2003, edited by Walter Siti, in a two-volume Mondadori edition. Sartarelli’s comprehensive selection derives from these volumes. His strategic solution to the formidable challenge of translating poetry from one language and culture to another seems to be that of remaining as close to literal transposition as possible, and to going from there to create a tension within the text. He does not take as many liberties as Norman MacAfee and Luciano Martinengo, the translators of an earlier selection (1982). His rendition conveys the narcissistic subjectivity, sensuality, and experimental lyricism so typical of Pasolini’s poetry. At times, the harsh lexical contrasts may be lost in translation, but the resulting naturalness in English cadence compensates for this. The poems are not only faithful to the fundamental meaning; they also capture much of the lyricism, musicality, and shape of the verse.

Sartarelli, best known for his translations of the novels of Andrea Camilleri (the Inspector Montalbano series), is himself a poet and brings to the translation a special sensibility, as well as insightful scholarship. The translation of Pasolini’s poem, ‘Goodbye and Best Wishes’, addressed to a hypothetical young fascist, captures Pasolini’s pathos and palpable sense of death. The closing lines linger in the mind: ‘Take this weight, boy, though you hate me. / Carry it yourself. It shines bright in the heart. / And I shall walk lightly on, always choosing / Life, and youth.’

Comments powered by CComment