- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Gender

- Custom Article Title: Gay Bilson reviews 'Women in Dark Times' by Jacqueline Rose

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

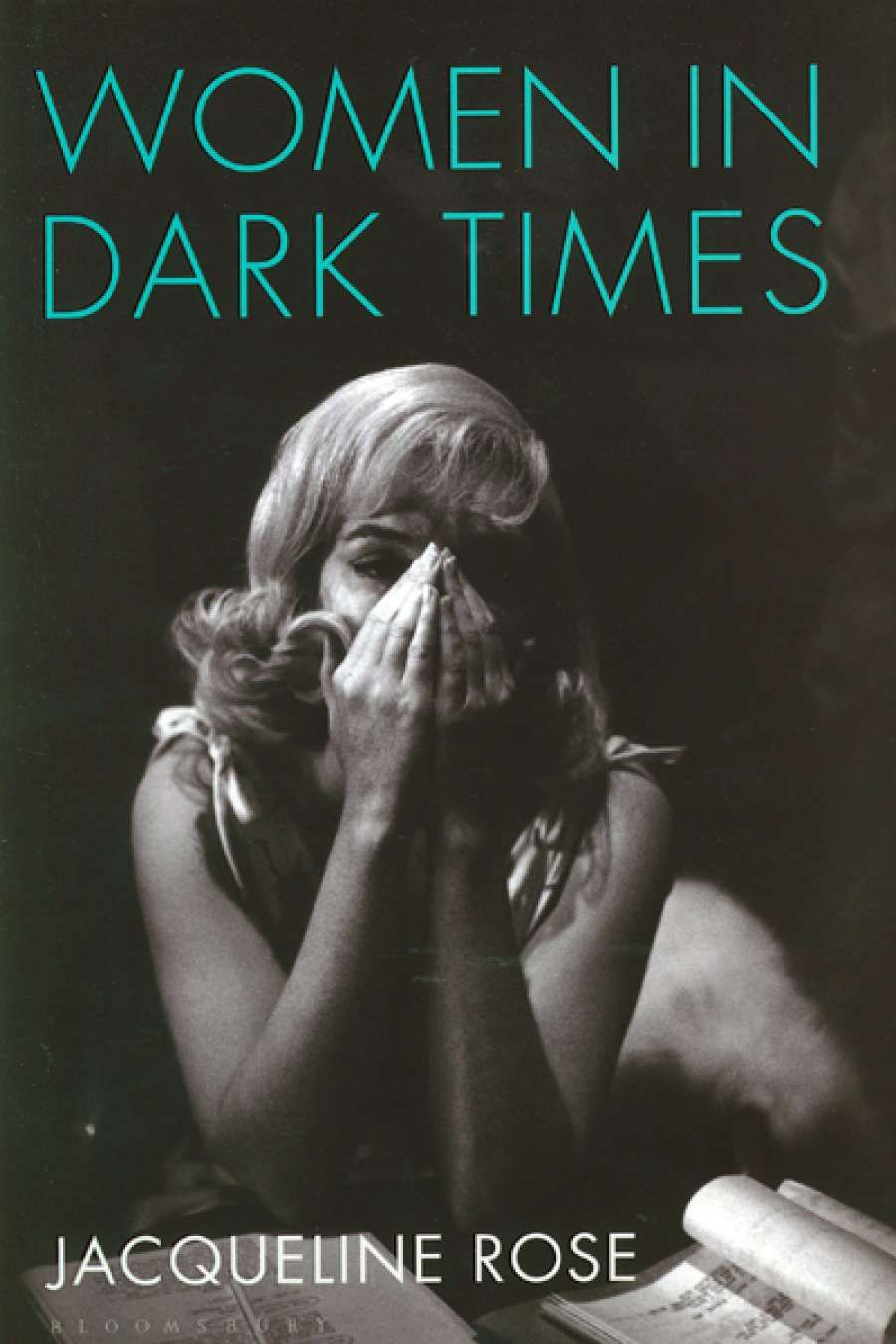

In a review of several books on motherhood (LRB, 14 June 2014), Jacqueline Rose – feminist, writer on psychoanalysis, English professor, ‘public intellectual’ – interprets Adrienne Rich’s belief that to give birth is to testify to the possibilities of humanity, as a variation on Hannah Arendt’s formulation, in an essay on totalitarianism, that ‘freedom is identical with the capacity to begin’. As bearers of new lives, women are thus the repositories of tremendous power, which is undermined by the patriarchy. Arendt’s collection of essays Men in Dark Times (1968) provided the framework for Rose’s exhilarating, disturbing, ‘scandalous’ (Rose calls for a ‘scandalous feminism’ in the preface) book, Women in Dark Times.

- Book 1 Title: Women in Dark Times

- Book 1 Biblio: Bloomsbury, $39.99 hb, 351 pp

‘Darkness is a better form of freedom,’ Thérèse Oulton tells Rose. Oulton is a remarkable, powerful artist, one of the ‘type[s] of genius’ among the portraits in the book. Oulton presumably means that to take on the worst, to fully examine it, to speak out about it in whatever creative way, is to gain immeasurable strength.

The book is divided into three parts, each section grouping three women who address this question of freedom with seemingly impossible courage. The first part, ‘The Stars’, looks at Rosa Luxemburg (revolutionary), Charlotte Salomon (artist), and Marilyn Monroe (actor, icon). Monroe doesn’t quite fit into Rose’s thesis; she seems more troubled victim than strong woman, though intelligent, thoughtful, and an engaged reader. The ‘Straits of Dire’, Monroe’s wonderful phrase for her own dark times, include not only ‘the infinite, insatiable nature of the desire [that Hollywood] promotes’, but also the reactionary politics of the time, the McCarthyism that dogged freedom, the capitalist American Dream. Monroe’s career was a brilliant one; she was also a failure by the standards of the American Zeitgeist: abused, promiscuous, addicted to prescription drugs, a suicide (or murdered?). She was ‘luminous’, writes Rose. To be considered luminous in the face of a tragic life is perhaps Monroe’s greatest achievement, but is surely also the judgement of men. In a recent documentary about the famous Pirelli calendar, Olivier Zahm (yes, let’s name and shame him) said, ‘A man’s desire is the greatest compliment that can be paid to a woman.’

The brave, political, and pacifist Rosa Luxemburg is known, at least in outline, to most of us, but the artist Charlotte Salomon was unfamiliar to me before I read Rose’s book. Between 1941 and 1943, Salomon produced one work, Leben? Oder Theater? (Life? Or Theatre?), which comprises more than 700 gouaches, including music and words: ‘The war raged on and I sat there by the sea and looked deep into the heart of humanity.’ Seven members of Salomon’s Jewish family, including her mother, committed suicide before World War II. Her abusive grandfather told her she might as well do the same, but Salomon refused, only to die in Auschwitz. Leben? Oder Theater? is housed in the Jewish Historical Museum in Amsterdam. Salomon stared her dark times in the face and produced something anguished and magnificent (there are some colour plates of pages from the work in the book).

Rose writes brilliantly about the ‘falsely harmonious world’ that fascism dictates, one that leaves no room for others. If this world permits no dissonance, Salomon’s allows for it. ‘Only a world that recognizes the other as other can set you free since the other’s freedom is inseparable from your own (if the other does not live, you die).’ Leben? Oder Theater? is on the one hand a work of unflinching memories, on the other, a bid for freedom.

The second section of Women in Dark Times is a compelling and intellectually imaginative essay on honour crimes, centred on the stories of three female victims. Rose expresses admiration for their sisters, the ones who go on telling the stories publicly, in the face of family and community threats. The horrific stories of Shafilea Ahmed, Heshu Yones, and Fadime Şahindal are similar but different. Rose quotes Mary Felstiner, who, in her biography of Salomon, wrote that genocide is ‘the art of putting women and children first’. This is to be reminded of ‘the capacity to begin’ that Arendt and then Rich introduced us to. And, if this matters, where on the scale of violence against women do honour killings sit? What exercises Rose is the place of honour killings in ‘an increasingly inequitable and dislocated world’. They don’t just take place in Pakistan and Turkey. How does our implicated Western culture deal with them?

‘Honour is about stopping people talking,’ an outreach worker tells Rose, who explores the connection between something that ‘belongs behind closed doors’ but is also ‘crucially public, belonging in some sense on the streets’. The killing happens inside the family, but the sense of shame felt by the father (and often the mother and siblings) is a public perception, a social reaction. The family has dealt with the shame, effaced the cause, but the community is still alive with rumour and gossip. The killing has, in effect, been an advertisement of shame, not a solution, even when it might be explained by those who killed, and those who condoned the killing, as culturally the only ‘acceptable’ course of action.

This most powerful section of Women in Dark Times is followed by essays on three articulate and internationally renowned artists: Esther Shalev-Gerz, Yael Bartana, and Thérèse Oulton. Shalev-Gerz and Bartana, both Jewish, deal outrageously, scandalously, with the trauma of World War II. Oulton’s abstract ‘landscapes’ (an inadequate description) deal with layers of memory, admission of damage.

Rose includes Oulton because she is the modern woman painter ‘who most compels and disturbs me – a mix I find irresistible’. For this reader, Oulton (like Monroe) doesn’t quite fit into the overall thesis of the book, even though this essay is itself compelling. I thought of two works that continue to disturb me. One is a 2003 video by the Argentinian Miguel Angel Rios, A Morir (‘til Death’). I was alone in a room at the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, DC when I saw it. The projection was huge, the sound loud. Four enormous black spinning tops spin ceaselessly; every now and then one is toppled over by another top. The soundtrack is simply that of the contact, the crash. It is mesmerising, frightening, repetitive. The other is a woman in black crocheting herself into a cocoon made from balls of red wool. She has reached her waist. Five of the nine women (three have been killed in the name of honour) whom Rose celebrates here are metaphorically unstitching the cocoon, speaking out against the unspeakable, most often against violence, the crashing of the spinning tops.

Jocelin, the abbot of the cathedral at the centre of William Golding’s 1965 novel, The Spire, ‘stood at the foot of the scaffolding, and part of the nature of woman burned into him; how they would speak delicately, if too much, nine thousand nine hundred and ninety-nine times; but on the ten thousandth they would come out with a fact of such gross impropriety, such violated privacy, it was as if the furious womb had acquired a tongue.’

Comments powered by CComment