- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

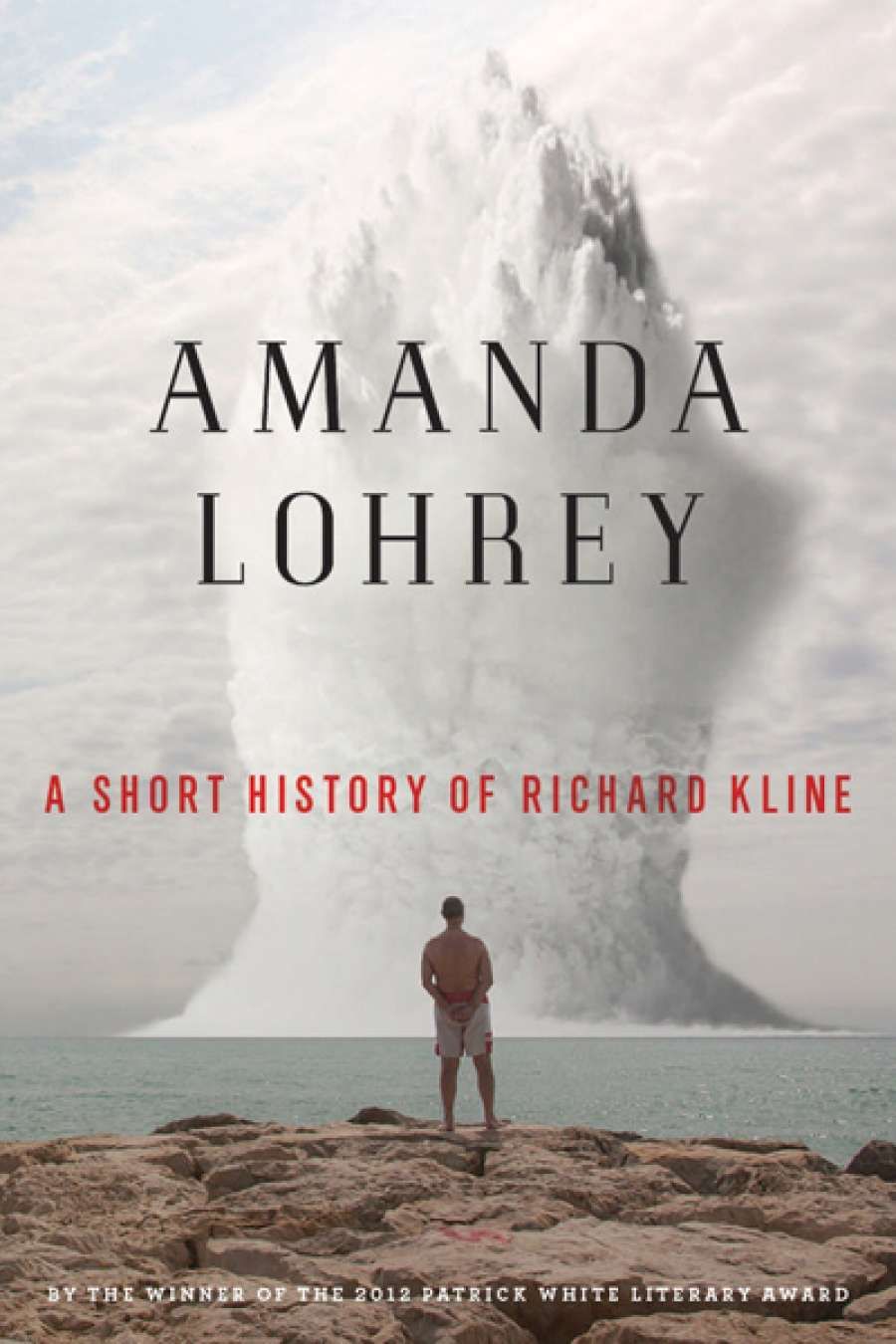

- Custom Article Title: 'A Short History of Richard Kline' by Amanda Lohrey

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

A prefatory note to this striking novel tells us that it is Richard Kline’s memoir of ‘a strange event that intervened in my life at the age of forty-two’. The following ‘short history’ interleaves sections of first- and third-person narration, shuffling the pieces of a reflective Bildungsroman that charts Richard’s emergence from a vague but oppressive childhood ‘apprehension of lack’ into something even more elusive.

- Book 1 Title: A Short History of Richard Kline

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $29.99 pb, 259 pp

Love, the novel’s first sentence suggests, will be its focus: ‘Until I met her, I confess that for most of my life I was bored.’ As a child, though, love seems limited. Richard’s ‘baffled disappointment’ is met by his mother’s ‘arsenal of clichés’. Through this white noise – ‘Tomorrow’s another day. You can only do your best’ – his glimpse of consolation is a perception that ‘in the heart of Nature was a mysterious force, and that force was the ground of any possible perfection’, one promising both ‘fruition and annihilation’.

The opening sections of the novel evoke the splinter of light and possibility that remain from this epiphany, pricking and flickering at the edges of ‘hauntings from some dark world of the psyche’. Cynicism and detachment grow around the self he forms, which, much later, he understands as ‘this construct, Richard Kline’, a creation, he reflects, that yearns to be ‘dissolved in whatever merciful solvent you could find.’

This is Lohrey’s seventh work of fiction, the first since her receipt of the 2012 Patrick White Literary Award. It is ten years since her last full-length novel, The Philosopher’s Doll (2004), in which a professional couple planning to have a child are faced with questions of energies beyond their control. In her 2008 novella, Vertigo, protagonist Anna’s mourning is expressed in her respiratory difficulties. This sense of a life in which one can no longer breathe, vividly evoked there and in Camille’s Bread (1995), is one that Richard imagines in similarly life-threatening terms as a virus-like ‘shiver of pain he could neither disgorge nor salve’ and the narrowing of figurative arteries ‘thickened and clogged by plaque’.

The novel returns to the inner-western Sydney streets of Camille’s Bread. It also returns to similar thematic terrain. Richard, like those protagonists, finds himself caught in the trap of ‘something called normality’ that rises up to devour his energy. His job becomes at once boring and overwhelming, and he rides ‘a grey tide of self pity’. Feeling as though a trapdoor has opened beneath his feet, he begins to drink more and suffers from insomnia and low energy, along with an anger that pervades ‘the whole messy labyrinth of his guts’.

While the results take him on a path that sits somewhere between those of Marita and Stephen in Camille’s Bread – she with her decision to spend a year with her daughter, he with a pursuit of purity through a practice of macrobiotics and shiatsu that ossifies into sanctimony – Richard’s distress erupts in road rage. That the moment involves Richard’s slapping a driver may be a nod to Christos Tsiolkas, but, more significantly, it illuminates the barely suppressed rage of so many of the urban Generation X characters on whom much of Lohrey’s recent fiction focuses. Although Richard enrols in a meditation course, fearing that his anger might cause him to ‘lose his grip on reality… tear and splinter into gaping viscera and jagged bone’, he is unable to use the word, citing instead a desire to ‘get more done with less fatigue’ as his motivation.

The dissolution – as ruthless as it is merciful – of the construct of Richard Kline is the focus of the novel’s latter part. Through his encounters with Hindu holy woman Sri Mata and the ‘rare intimacy’ he shares with urban monk Martin, Richard is accompanied by ‘his old ally, his intellect’, and the cuts inflicted by his cynicism on growth’s fragile seedlings.

One of Lohrey’s concerns is the way ‘the unfocused anger that men of a certain age tended to exude’ hobbles and blights their own lives and those of others close to them, with its ‘razor-cut irritability’ and hair-trigger defensiveness. A series of deft images conveys Richard’s misalignment. He feels like a harnessed horse and ‘an instrument un-tuned’.

In an interview with Charlotte Wood for The Writer’s Room, Lohrey describes ‘allowing the unconscious to have a voice in the narrative, to open up a space of mystery’. Through the interleaving of internal and external perspectives, and the employment of forceful imagery, Lohrey explores questions of idolatry, belief and mysticism in and through Richard. Her perceptive analysis irradiates each of the novel’s questions. The more overt politics of her early work is just as vibrant here, where the political is staged in the interior and domestic spheres.

When Richard believes he is ‘the agent of a small miracle’ in the life of a friend, and when he can to ‘listen without irritability’ to the vagrant anecdote of an acquaintance, he begins to understand that gratitude is one thing he has lacked. The novel that Richard loves as a young man is Hermann Hesse’s Siddhartha (1922). As his rage softens, he remembers the line ‘and the bird in my breast had not died’. The tendrils of a love story climb through his dreams and learning, and trail beyond the space of Lohrey’s lyrical, bold exploration with a promise of flowering and song.

Comments powered by CComment