- Free Article: Yes

- Contents Category: Essay Collection

- Review Article: Yes

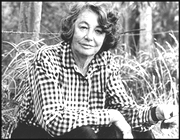

Elizabeth Jolley’s personal and publishing history is well known. She migrated from the United Kingdom to Western Australia with her husband, Leonard, and their three children in 1959, when Leonard was appointed Librarian at the University of Western Australia. Although she had been writing from a young age and had brought a great deal of manuscript material with her, it was not until the late 1960s that she had stories published. Fremantle Press published her first book, Five Acre Virgin and Other Stories (1976). More publications followed in rapid succession, and Miss Peabody’s Inheritance and Mr Scobie’s Riddle, Jolley’s third and fourth novels, both appeared in 1983.

Miss Peabody’s Inheritance begins abruptly with a mysterious statement, ‘The nights belonged to the novelist’, one which is repeated periodically and becomes a kind of leitmotif in the novel. This reference to the dark realm of the night suggests something hidden, something outside the ordinariness of daytime, a time of dreams, of imaginative licence, ‘a world of magic and enchantment’. It is followed by what seem to be notes for a story: ‘I have a Headmistress in mind, you know, a tremendously responsible sort of woman, the novelist’s large handwriting was black on large sheets of paper’, and Peabody’s doubled narrative mode – its metafictional structure – is established. A novel-in-progress is recounted in part in a series of letters from an Australian romance novelist, Diana Hopewell, to Miss Peabody. This narrative is embedded within the main story, concerning the unlikely but intimate relationship that develops, through their correspondence, between the novelist and Dorothy Peabody, an insignificant, middle-aged woman who lives with her invalid mother in London and works as a stenographer.

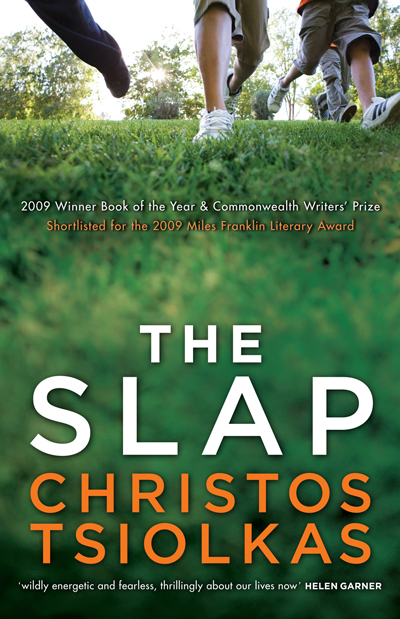

Miss Peabody's Inheritance (UQP, 1984)

Miss Peabody's Inheritance (UQP, 1984)

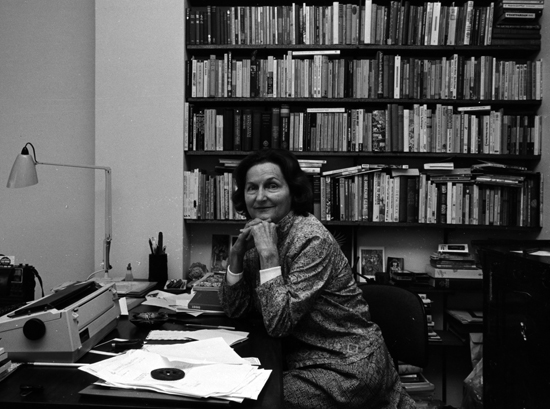

Buy this bookJolley was herself an inveterate note-taker and letter writer; she valued epistolary friendships in her own life. Her correspondence with her father, for example, extended throughout his life from her schooldays. Jolley described her grief at his death as being in part a loss of that deep association, ‘a bereavement of not writing letters’. Putting the story of the headmistress, Arabella Thorne, into the letters of the imagined novelist, Diana Hopewell, gave Jolley the form she needed to develop a character like Miss Thorne in all of what she called her ‘awkwardness’. She discusses this in her essay, ‘A Scattered Catalogue of Consolation’, where she says: ‘Writing in letters allows a great deal of freedom – repetitions, poor but vivid phrases, purple passages of description, these are all excused in this rapid and personal method of communication.’

The energy of the novelist’s letters, their personal directness and the often ludicrous, sometimes outrageous, events and relationships they record contrast with the timid conventionality of Peabody’s life, mirrored in her letters. Peabody had written to Hopewell after reading her novel, Angels on Horseback. The story of ‘beautiful young schoolgirls and their strange and wild riding lessons’ brought ‘something exciting into my life’, she writes, while ‘the loneliness and the harshness of the Australian countryside fitted so exactly with my own feelings ...’ The novelist’s unexpected reply, asking about Peabody’s life, and beginning to tell the story of her new novel, excites Peabody. She imagines the novelist’s life, using the clichés of romance fiction that drew her to Angels on Horseback: ‘While reading the novelist’s first letter Dorothy seemed to see her, Diana, dismounting from her horse at sunset to open the gates leading to her property. The dry grass would be pink in the light of the setting sun, Dorothy thought, like in the novel ...’ Hopewell is linked in Peabody’s mind with ‘Diana, the Goddess of the Hunt [who] would be a tall woman graceful and shapely about the neck and breast’. At the same time, the novelist’s questions, ‘Are you in love? … What sort of dresses do you wear? Please tell me all about yourself!’ both startle Peabody and prompt her to re-imagine her own life, whose ‘routine[s] never varied’. She develops her own fictions: for example, a young lover killed in the war. Peabody’s life is gradually transformed by the letters, which she saves to read, re-read, and answer, always at night, while her responses, limited though they seem, encourage Hopewell to continue with her novel. Peabody, too, experiences a ‘sudden and strange bereavement’ when she learns that Hopewell has died, ‘one of not being able to think about and compose and write the letters’. Because of them, ‘Miss Peabody had known happiness’.

‘Jolley was herself an inveterate note-taker and letter writer’

The rapid movement among the narratives and the narrators of Miss Peabody’s Inheritance requires constant alertness from the reader. Much of the pleasure of this novel comes from following their intricate interweaving, as well as recognising and revelling in their differences, of tone and style, tense, and narrative perspective. Not only are we as readers active interpreters of the shifting narrative of Miss Peabody’s Inheritance, we participate in the relationship established between the novelist and Miss Peabody, between writer and reader within the novel. It shifts as Peabody moves from being a naïve reader, bewildered by the gap between the events and relationships described in Hopewell’s novel and her own dreary life, which ‘not from her own fault at all, had become a series of clichés and platitudes’, to her final position as Hopewell’s successor. By the end, Peabody understands that there is indeed a ‘thin line between truth and fiction’. In the meantime, she blunders around London trying to find a pattern in the London sky to match the one that, according to Hopewell, marks the entrance to her Australian property. Later, she tries to find out where An Ideal Husband is playing; believing the fiction that Miss Thorne and her travelling companions will be there. However, we recognise that Peabody’s idea of the physical freedom and power of the Diana figure is far from the reality of the novelist’s actual situation, when an uncharacteristically typed page, relating a series of botched operations and their result, mysteriously appears in one of her letters.

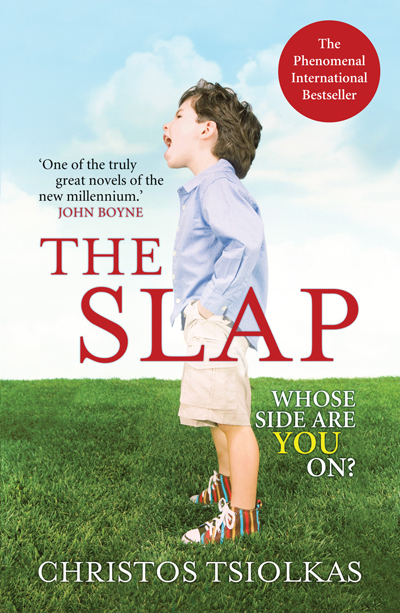

Miss Peabody's Inheritance (Penguin, 1985)

Miss Peabody's Inheritance (Penguin, 1985)

Buy this bookHopewell’s most important role, though, is as Peabody’s guide. When Peabody struggles to make sense of the letters, with their plunging black writing criss-crossed with other colours, Hopewell explains: ‘The structure of my story, … is so complicated that, in my notes, I have to use different colours, you know, green ink to remind me of what Edgely is doing, red for Thorne and blue for Snowdon.’ Peabody adjusts to the lack of order: ‘Sometimes the letters were disjointed and the novelist sent only a fragment which Dorothy guessed would slip into place sooner or later, unless, of course, it was discarded. Writers did not always use everything they wrote, the novelist explained.’ And she is instructed on the correct response to the writing and her role as reader:

You will notice … that I am writing the story of Miss Thorne in the present tense. This makes it all very immediate ... If you feel disturbed and strange this is all perfectly natural … If you feel emotionally involved that is natural too. The writing is packed, it is dense writing, emotions on several levels packed in. It is, I hope, a novel of existence and feeling. A reader can be as involved as he wishes and some readers will fight off this involvement. Don’t worry. Read on.

Not only does Peabody read on: she writes, and Hopewell responds enthusiastically to her often stilted and clumsy letters: ‘And do you know I love your handwriting. It excites me.’ An emphasis on the physical presence and power of writing – later Peabody declares that she loves the novelist’s writing – suggests that through their correspondence Peabody and Hopewell experience an emotion as urgent and thrilling as any more conventional erotic adventure.

‘Not only are we as readers active interpreters of the shifting narrative of Miss Peabody’s Inheritance, we participate in the relationship established between the novelist and Miss Peabody, between writer and reader within the novel’

This process of the education of the reader is part of the comedy of Miss Peabody’s Inheritance. It is one that finally enables Peabody’s physical migration from London to Western Australia, and her initiation into the novelist’s inheritance. Her journey, and others in the novel, both reflect and parody Jolley’s own migration to Australia. Peabody travels to meet her epistolary friend, only to find that Hopewell has died, and that far from being the active horsewoman, the mythic Diana of Peabody’s imagination, she has been an invalid in a nursing home. However, Peabody realises not only that, ‘There were enormous possibilities. She had only to look at her bulging handbag’ in which she has carried all the novelist’s letters, but also that she no longer needs to go to see Diana’s farm. She has been initiated into her inheritance.

Within the internal narrative, the idea of the initiation, particularly of innocence, is a major theme whose consequences are often unexpected. Thorne thinks of herself as creating a cultural centre at Pine Heights, initiating the schoolgirls into aspects of European culture. She plays the cello, reads Othello, and reveres Richard Wagner. She initiates Gwendaline Manners, one of her students, into travel and culture as Gwenda accompanies Thorne, her great friend Matron Snowdon, and her assistant, Miss Edgely, on their annual pilgrimage to Europe. Gwenda’s education becomes a sexual one when Thorne spends a night, one that is ‘idyllic, tender, hilarious and ludicrous’ with the girl. Yet none of this is straightforward. Thorne’s greatest interest in Othello is in planning the costumes for the school production; she is aware that Mr Minsk, the music teacher at Pine Heights, listens to her cello playing with barely concealed horror; the high point of the European tour is not the Wagner Festival in Munich but the annual Wine Festival at Grinzing. And while Thorne thinks of Gwenda in relation to the innocent girl in a poem by Goethe, she also realises that Gwenda’s ambition to marry and have four children is an understandable one.

Miss Peabody's Inheritance (UQP, 2014)

Miss Peabody's Inheritance (UQP, 2014)

Buy this bookFrequent references to cultural texts are not simply part of the farcical level of the novel. Peabody has read the opening of Great Expectations to her mother, and Peabody’s life is turned upside down, as Pip’s is there, by her friendship with the novelist. Edgely’s jealousy of Thorne’s interest in Gwenda is amplified by several quotations from Othello. And the promise of romance fiction to fulfil unrealistic expectations is also radically reduced. Thorne realises she has mistaken Mr Frome’s interest in her and that she must give Gwenda up to him. After a long night of self-reflection, she is ready to return to the sanctuary of Pine Heights, recognising that though Edgely is completely incompetent in her work and intensely irritating to Thorne, they are essential to one another. Not only does Edgely have nowhere else to go, Thorne is also, without Edgely, alone. At the end of Hopewell’s final letter, she muses: ‘A great writer … once wrote something about continuing life at a lower level of expectation’, of which, she thinks, ‘something … will be apparent by the end of the book’, and indeed it is.

Miss Peabody’s Inheritance is a comedy of women’s lives and friendships, with its potentially serious recognition that sexuality is not confined to the young and that women share homoerotic lives and its comical treatment of aspects of those lives; the water fight between Snowdon and Thorne, the trail of broken beds the travellers leave across Europe, Peabody’s confused arousal as she reads of these things. Names of characters are both amusingly apt and often linked to more serious referents while characters and locations are connected across the narratives. Thorne and Hopewell are each goddesses to Edgely and Peabody, who are both small, incompetent, and stupid. Peabody works at Fortress Enterprises, and Pine Heights is a kind of protected pastoral for Thorne, while Flowermead, the small private hospital where Diana Hopewell has been confined, shares these qualities. Some scenes are pure slapstick; Thorne knocking a paper cup of hot tea into Edgely’s lap during their trip with Snowdon to the wheatbelt; Peabody feeling cheeky drinking brandy with the Fortress Enterprises staff at the local bar on a Friday afternoon. But as well as the often farcical comedy, and the word play Jolley delights in, there is also a level of understanding of both the courage and the pathos of these small lives.

The novel’s concerns – with the dynamic interaction between writing and reading, with the social constriction and limitations of women’s lives and the contrasting potential growth and freedom of their imaginative lives, with the pleasures and dangers of initiation, with the expression of female sexuality, and with issues to do with migration and loss – are complicated by its self-conscious level of what Paul Salzman calls ‘narrative entangling’. Notes Jolley made for a public reading from Miss Peabody’s Inheritance include the remarks: ‘The 1st short piece is from the novelist’s letter … The second passage relates to Miss Peabody’s actions. I am not well enough up in literary theory to say who has written this.’ This demonstrates her awareness of the novel’s potential to attract complicating theoretical readings, treated as another comic area in the novel, and her own amusement at the innocent writerly position she constructs for herself here. An arch dissembler, a wise and witty and always surprising writer, Elizabeth Jolley is also a great entertainer, and Miss Peabody’s Inheritance offers multiple pleasures for its readers.

References

Bird, Delys, ‘Now for the Real Thing: Elizabeth Jolley’s Manuscripts’, in Elizabeth Jolley: New Critical Essays, eds Delys Bird and Brenda Walker, Collins Angus & Robertson Publishers, 1991, 168-179.

Dibble, Brian. Doing Life: A Biography of Elizabeth Jolley. UWA Press, 2008.

Jolley, Elizabeth. Miss Peabody’s Inheritance. UQP, 1983.

Jolley, Elizabeth, ‘A Scattered Catalogue of Consolation’, in Learning to Dance: Elizabeth Jolley : Her Life and Work, ed. Caroline Lurie, Viking/Penguin, 2006.

Milech, Barbara H, ‘Becoming “Elizabeth Jolley”: The First Twenty Years in Australia’, in Australian Literature and the Public Sphere, eds Alison Bartlett, Robert Dixon and Christopher Lee, Association for the Study of Australian Literature, 1998.

Salzman, Paul. Helplessly Tangled in Female Arms and Legs: Elizabeth Jolley’s Fictions. UQP, 1993.

Further Reading

Jolley, Elizabeth, ed. Caroline Lurie. Central Mischief: Elizabeth Jolley on Writing, Her Past and Herself. Viking Penguin, 1992.

received include: The Patrick White Award in 1989, The Age Book of the Year Award for A Kindness Cup in 1975, the 1980 James Cook Foundation of Australian Literature Studies Award for Hunting the Wild Pineapple, the 1986 ALS Gold Medal for Beachmasters, the 1988 Steele Rudd Award for It's Raining in Mango, the 1990 NSW Premier's Prize for Reaching Tin River, and the 1996 Age Book of the Year Award and the FAW Australian Unity Award for The Multiple Effects of Rainshadow.

received include: The Patrick White Award in 1989, The Age Book of the Year Award for A Kindness Cup in 1975, the 1980 James Cook Foundation of Australian Literature Studies Award for Hunting the Wild Pineapple, the 1986 ALS Gold Medal for Beachmasters, the 1988 Steele Rudd Award for It's Raining in Mango, the 1990 NSW Premier's Prize for Reaching Tin River, and the 1996 Age Book of the Year Award and the FAW Australian Unity Award for The Multiple Effects of Rainshadow.