- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Young Adult Fiction

- Custom Article Title: Living in limbo

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Living in limbo

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In the essay ‘Pay Attention to the World’, written shortly before her death in 2004, Susan Sontag argues that fiction is ‘one of the resources we have for helping us to make sense of our lives … [it] educates the heart and the feelings and teaches us how to be in the world’. While Sontag’s insight recognises the power of literature in general, the qualities she identifies are particularly significant in young adult fiction. Genius Squad and At Seventeen are two examples of the ‘rite of passage’ novel, where adolescent characters’ quests for self-discovery illuminate parallel themes in the lives of teenage readers.

- Book 1 Title: Genius Squad

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $18.95 pb, 435 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

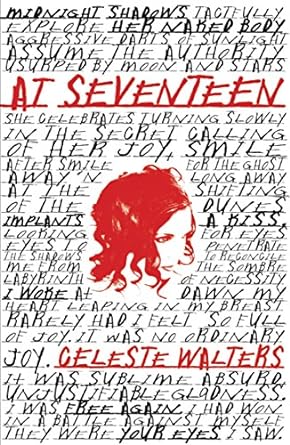

- Book 2 Title: At Seventeen

- Book 2 Biblio: UQP, $18.95 pb, 216 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

Celeste Walters’s At Seventeen presents a similar plot to her previous novel, Deception (2005). Though the former dealt with the personal struggles of an adolescent male, At Seventeen introduces seventeen-year-old Catherine, whose attempts to uncover family secrets are constantly thwarted by self-doubt and social pressures. Catherine is ‘not milk and water like most’. A literary romantic, she is fragmented and disillusioned by the boarding-school experience, which is an exercise in ‘learning to hate’: at best banal and lonely, at worst, sinister and perplexing. The story focuses on Catherine’s day-to-day existence following her abandonment when her parents relocate to Spain. The death of Catherine’s grandmother, however, necessitates a reunion that leads Catherine to resolve some familial mysteries and to explore her own latent sexual desires.

Walters’s dedication, ‘for the girls’, unapologetically delineates the novel’s audience for whom Catherine’s defiantly feminine subjectivity has been drawn. The desolation and melancholy of transitional states such as Catherine’s is sensitively evoked during an airport scene where the image of ‘a yawning chrysalis-turned-corridor’, from which ‘defenceless’ passengers are born, becomes a metaphor for Catherine’s protracted delivery into adult womanhood.

Catherine’s yearnings for a dashing suitor, like those of her idol Anna Karenina, prove incompatible with droll reality. Walters, with refreshing irony, deflects the possibility of cliché in Catherine’s reflections on the experience of ‘first love’: ‘My life began the moment I saw you (sounds like a song or a very bad poem. True, though).’ Intense scenes of sexual fantasy fuelled by the awakening of Catherine’s imagination hint that this is a novel suitable for the older teen bracket. Similarly, a subplot involving a seductive liaison between Catherine and her female sports teacher is not adequately resolved.

What Walters’s narrative successfully presents are honest depictions of fluid morality. Catherine’s realisation that her parents and grandparents are concealing generations of secrets and betrayals moves toward the revelation that all human beings are fragile in the face of love, that their choices are sometimes selfish and their judgements fallible. This is a significant insight, but in young adult fiction, it is also an all too familiar one. The more remarkable questions raised in the novel – ‘What happens when you can’t forgive? When the rules are broken? […] At what point does love make you want to kill?’ – remain unanswered.

If At Seventeen is ‘for the girls’, then Genius Squad is definitely for the boys. In Catherine Jinks’s sequel to Evil Genius (2006), which introduced Cadel Piggott, the teenage computer wiz continues his techno-rampage through dangerous moral territories. Now fifteen, Cadel is ‘living in a kind of limbo, with nothing whatsoever to do’. He is imprisoned in a volatile foster home where his hyper-intelligence isolates him from his ‘totally screwed up’ and ‘abysmally stupid’ siblings. While he may be able to mastermind the most complex of computer codes, Cadel’s mission to discover the true identity of his parents is, like Catherine’s in At Seventeen, an essentially human one. His epic journey through an array of possible parents, including the sinister genetic manipulator, Prosper English, leads him to a group of hospitable hackers in a youth hostel. Although Cadel seems to have here found his place in the world – whether this ‘genius squad’ is entirely on his side or just another of English’s cunning entrapments – is a question that supplies much of the narrative tension.

Cadel’s is ‘a life of subterfuge, manipulation and despair’ which Jinks explores through bleak images of a frightening dystopic existence. Everyone close to Cadel has ‘died’, ‘disappeared’, ‘lost their mind’ or ‘been killed’. The plot revolves around the combat of planned assassinations of mutant human beings and information systems. Themes of paranoia and perpetual surveillance are extreme as each chapter develops in complexity. Yet, at times, Cadel’s ‘gloomy impatience’ belongs to the reader. Jinks’s language is rich in graphic detail but, just as the story is focused on an interpretation of digital realities, the text itself takes on a coded resonance requiring decryption. If there is a broader moral statement to be deciphered (the dangers of multinational greed, the questionable ethics of cloning), it remains ambiguous and, perhaps, past its topical prime.

Sontag moves toward the suggestion that fiction truly succeeds when some deeper elements of philosophical revelation or psychological truth underlie the surface plot. Is there more than a captivating narrative to At Seventeen and Genius Squad? No. Yet are such insights what readers of adolescent fiction seek? Possibly not. These two novels, though vastly different in genre, depict engaging tales of emotional growth that will aid young adults to make more sense of the world.

Comments powered by CComment