- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: When Nellie met Melba

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

On page sixty-two of Ann Blainey’s thoroughly researched, excellently written and beguilingly human biography of Nellie Melba there occurs a transition that is simple but that defines, in an instant, the moment the singer went from learner to legend. It happens when the young singer, under the wing of Madame Marchesi (née Mathilda Graumann; nickname ‘the Prussian drill-master’), is ready to make her public European début and requires a new surname. ‘Armstrong’ had to go; in its place, there had to be something ‘distinctive and memorable’:

- Book 1 Title: I am Melba

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $32.95 pb, 386 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

She and Nellie began examining Australian names. Richmond and Victoria yielded nothing, and then they came to Melbourne. If they chopped off the last five letters and added a final ‘a’, they would coin a name so simple that any European could spell and pronounce it immediately. It seemed the perfect solution …

Thus on 30 December 1886, young Nellie went to her début with a new last name. It was, of course, a triumph, and the Paris critics had no trouble in raiding their lexicons for praiseworthy words. With that, Blainey dispenses with ‘Nellie’ and henceforth calls her subject ‘Melba’. It is a small moment, but it sums up the very duality of the woman born Nellie Mitchell in 1861, the youngest of eight children, whose determination to sing and supreme ability to do so have often popularly displaced her vulnerabilities. Was ‘Melba’ (as distinct from ‘Nellie’, or even ‘Mrs Armstrong’) purely a professional role, to be shrugged off like a costume once off the stage? Or was it inextricable from the whole person? Blainey, in believing the latter, is convincing in her argument:

Thanks to her secure upbringing and robust self-image, and Marchesi’s expert tutelage, she slipped effortlessly into the role of Melba and felt no confusion. ‘I am Melba,’ she would say proudly, and in her eyes and feelings the name comfortably embraced and fused all aspects of her personality.

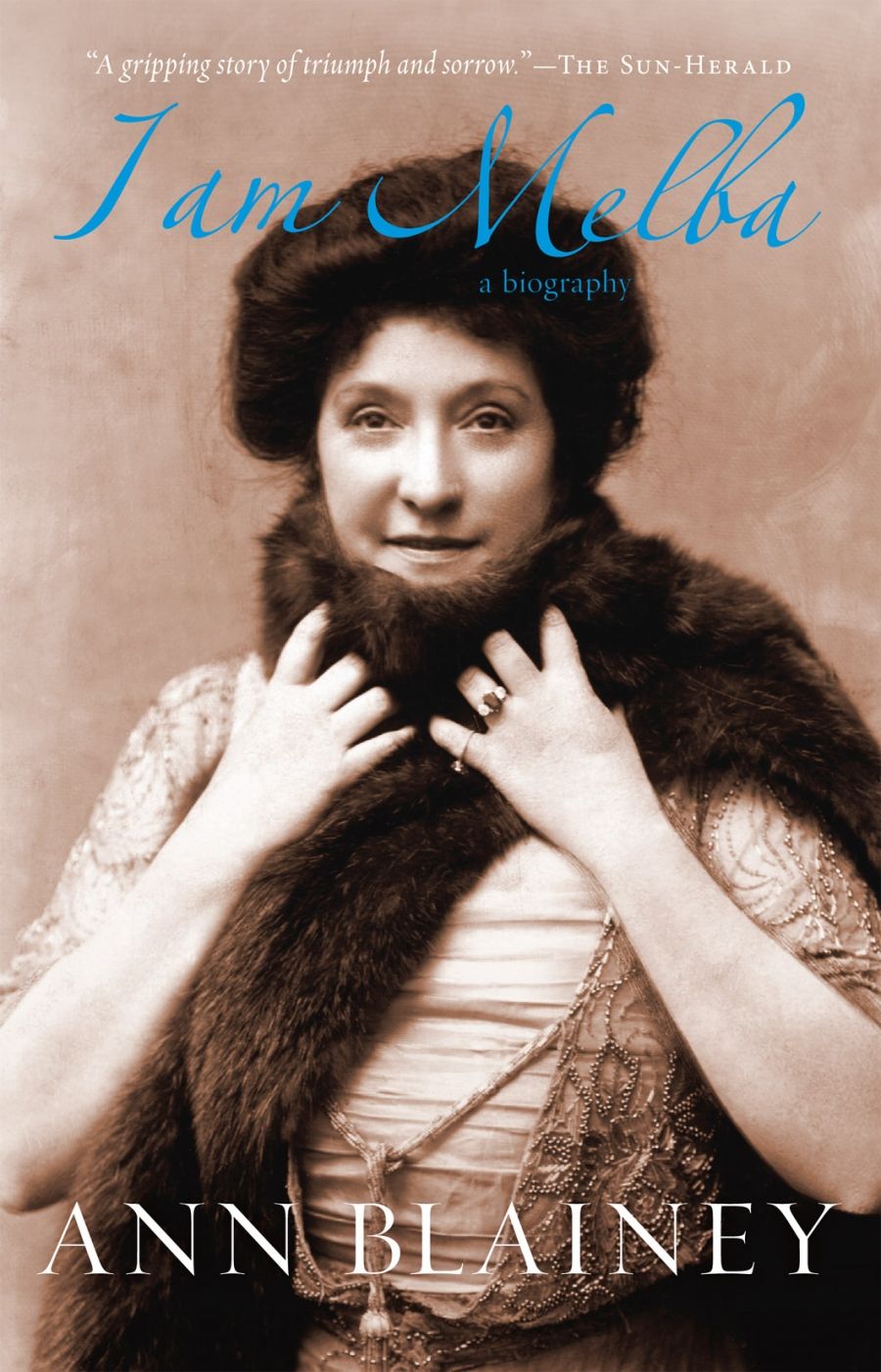

Part of the charm of Blainey’s account is the balance it maintains between the various aspects of Melba’s character. The author never disregards Melba’s musicianship, which was considerable, or her technique, which was formidable; instead, she allows these qualities to coexist with the complexities often eclipsed by fame or modified (even completely changed) by scuttlebutt. There is something of the art-restorer about Ann Blainey: she quietly and deftly, without putting herself in the frame, removes the patina of previous biographies or various historical recollections, to uncover layers that make one view the result in a different light. This is not merely a ‘what Melba did next’ biography, with endless lists of roles and reviews, but a more involved, and involving, scrutiny that shows Melba to be as enchanting and, perhaps, as enigmatic as the half-smile she wears in the cover photograph. A chronology and discography would have been welcome, but they are easily found elsewhere.

Melba’s life has been previously accounted for in at least five biographies, the more recent by John Hetherington (1967) and Thérèse Radic (1986), not to mention Melba: A Family Memoir (2000), by the diva’s granddaughter, Pamela Vestey. Blainey pays tribute to these books, but points out various chronological gaps that needed filling in, such as details of Melba’s American tours, and the benefits of other resources hitherto inaccessible or unexplored: Melba’s own news clippings; letters from one of Melba’s sisters, Belle; the diary of one of her secretaries; and the divorce papers of Melba and Charles Armstrong.

From the vantage point of the early twenty-first century, it is easy to recall Melba as an anachronism: an old-fashioned diva in a cloche hat and furs who spent most of her professional life elsewhere, collecting jewellery and rave reviews in equal proportion while being commemorated in peaches and toast; whose legacy is recalled via a series of what she herself referred to as ‘scratchy, screeching’ recordings; and who took a long time to say goodbye (‘Doing a Melba’ is, as Blainey reminds us, a long established part of the Australian lexicon). Besides, her greatness has been eclipsed by that other great Australian mistress of bel canto, Joan Sutherland. Why would Melba matter today?

The short answer is: she does. Not purely for her fame, which was, of course, considerable and cannot be disregarded, but for her extraordinary talent. Her rival, Mary Garden, memorably described Melba’s last high C in Act I of La bohème as ‘a ball of light’. Yet Melba’s artistry, let alone her durability as an performer, owe as much to the times in which she sang as what she sang. It is important to remember that Melba, a superb musician with an excellent memory, entered European opera at a time when performance more properly meant technique first and stagecraft a very poor second: indeed, the redoubtable Madame Marchesi, operatically orthodox to her corset straps, forbade even gesturing, lest it jeopardise the purity of the sound. This was all very well for earlier Rossini or Bellini, where the voice said it all, but not for the more contemporary likes of Verdi or that young upstart Puccini, where something resembling acting was required. Melba, on the cusp of two ages, really had no alternative but to embrace the more romantic, and realistic, style. For this ‘young, vigorous and attractive woman’, it was to seal her fame in Europe, North America and her native land.

She also had the advantage of firsthand acquaintance with the pre-eminent composers of the day: Verdi, Puccini, Gounod, Thomas, Mascagni, Leoncavallo and Massenet, who likened her voice to a Stradivarius. Mahler, who conducted her at the Vienna Opera, was more disparaging, calling her voice ‘mechanical’ and saying he’d rather hear a clarinet. Sometimes, though, there were mistakes: her single Brünnhilde, in Siegfried, at the Metropolitan Opera, New York, on 30 December 1896, was like, in her words, ‘battling some immense monster’; other Wagner, such as Elisabeth in Tannhäuser and Elsa in Lohengrin, fared better.

One of the most enduring Melba myths is her infallibility; that only in her last years did her health begin to suffer. In fact, as Blainey explains (and to which the index attests), her life was a catalogue of major and minor ailments, ranging from blood poisoning, pneumonia, bronchitis and what she called ‘irrigations’, to seasickness, colitis and infected teeth. In the summer of 1890 she was forced to stop singing for three months after a nodule was diagnosed on her left vocal cord – a result of what the French call coup de glotte, or attacking a note hard. This said, Melba was hardly the serial canceller: it was hard to get her off the stage once she was on it, and the old piano was often wheeled in from the wings so Madame could accompany herself in Home, Sweet Home.

She could certainly travel, too. Seasickness notwithstanding, Melba’s various voyages and train journeys in the name of opera took her through Britain, continental Europe, the United States and parts of Australia – accruing celebrity as modern divas rack up frequent-flyer points. No wonder she was the most celebrated singer of the day: you couldn’t miss her.

Melba’s offstage life had its sad times. Her unhappy marriage to the volatile Charles (‘Charlie’) Armstrong resulted in one son, George, who didn’t see his mother between 1893, when, as a ten-year-old, he was taken by his father from England to Texas, and 1904. Other aspects of Melba’s private life, which these days would be fodder for New Idea or Hello!, managed to be fairly discreet and in keeping with the social omertá of the day. For example, her affair, early in her career, with Philippe, Duke of Orléans, the son of the heir to the abolished French throne, the Comte de Paris, seemed to make only her divorce papers without hitting the mainstream ones; subsequent romantic involvements were also not mentioned. Only the Australian press – most notoriously, the Sydney Truth and the poison pen of John Norton – went for the Melba jugular. Norton, in a particularly splenetic mood, wrote of Melba’s

Champagne Capers, Breach of Public Faith, Outrages against Good Manners, and Insults to Australian Citizens … You are a constant infliction to maddened managers, a harrowing handful to harassed hotel keepers, a terrorism termagant to trembling time servers.

This was hardly the same Melba who loved her country – indeed, in 1914, she raised a fortune in donations to aid the war effort – and whose funeral procession in 1931 attracted mourners in their thousands.

Mostly, though, Nellie Melba was the object of admiration. Is it going too far to call her a legend? Not really. In her book, Ann Blainey stops short of this appellation, but there is no mistaking the enthusiasm. Perhaps Melba was more a down-to-earth legend, who never quite lost her steel as the girl from Richmond, and who sang because she wanted to. There were the mansions (Coombe Cottage, at Coldstream, near Lilydale, is still home to her granddaughter), the jewels from the tsar, the king and the entrepreneurs, the piles of shipping trunks, the maids, the cooks and the gardeners; but there was also that creaky piano in the wings: Home, Sweet Home was always on her mind.

Comments powered by CComment