- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Sins of the fathers

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Each of these memoirs – Births Deaths Marriages: true tales, by Georgia Blain, and The After Life: A Memoir, by Kathleen Stewart – is the work of an accomplished novelist, and each writer is well aware of the risks involved in the shift of mode. If the novel, as Blain maintains, provides a place for the writer to hide, the memoir is the place of self-exposure, of speaking the truth, or a version of the truth. Although it is the wellspring of all creativity, to write about the life, to pin it down, is in a sense to distort it. Memory is unreliable and bias is inevitable. There is also the problem of exposing others, and the others in each of these memoirs are easily identified. Each writer faces the challenges of memoir in an entirely different way. The narrative voice in Births Deaths Marriages is thoughtful and contemplative; the account qualified at times by self-doubt. Stewart’s account, on the other hand, is sure of its truth. It is dramatic, forceful and defiant.

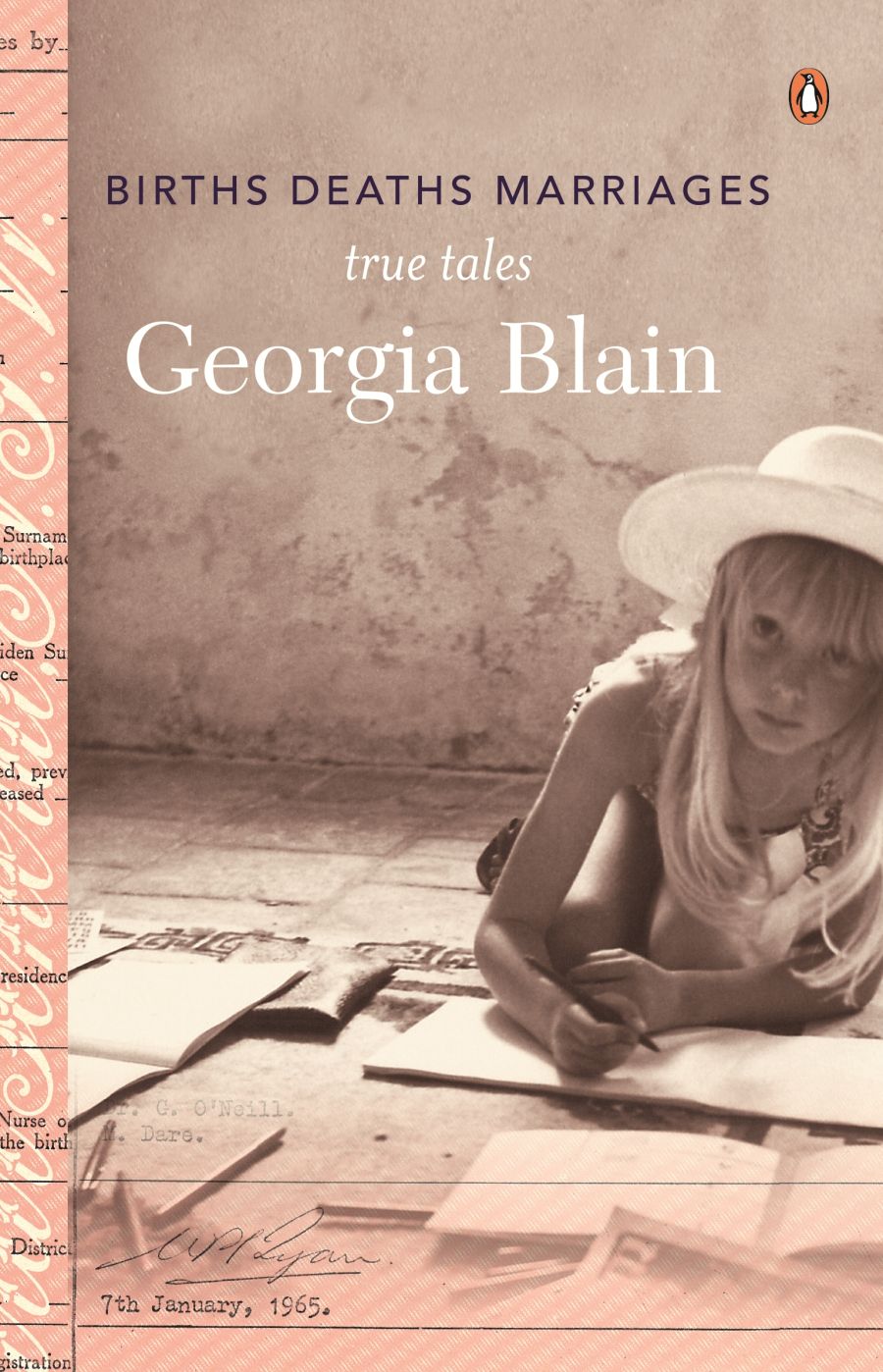

- Book 1 Title: Births Deaths Marriages

- Book 1 Subtitle: True tales

- Book 1 Biblio: Vintage, $24.95 pb, 224 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

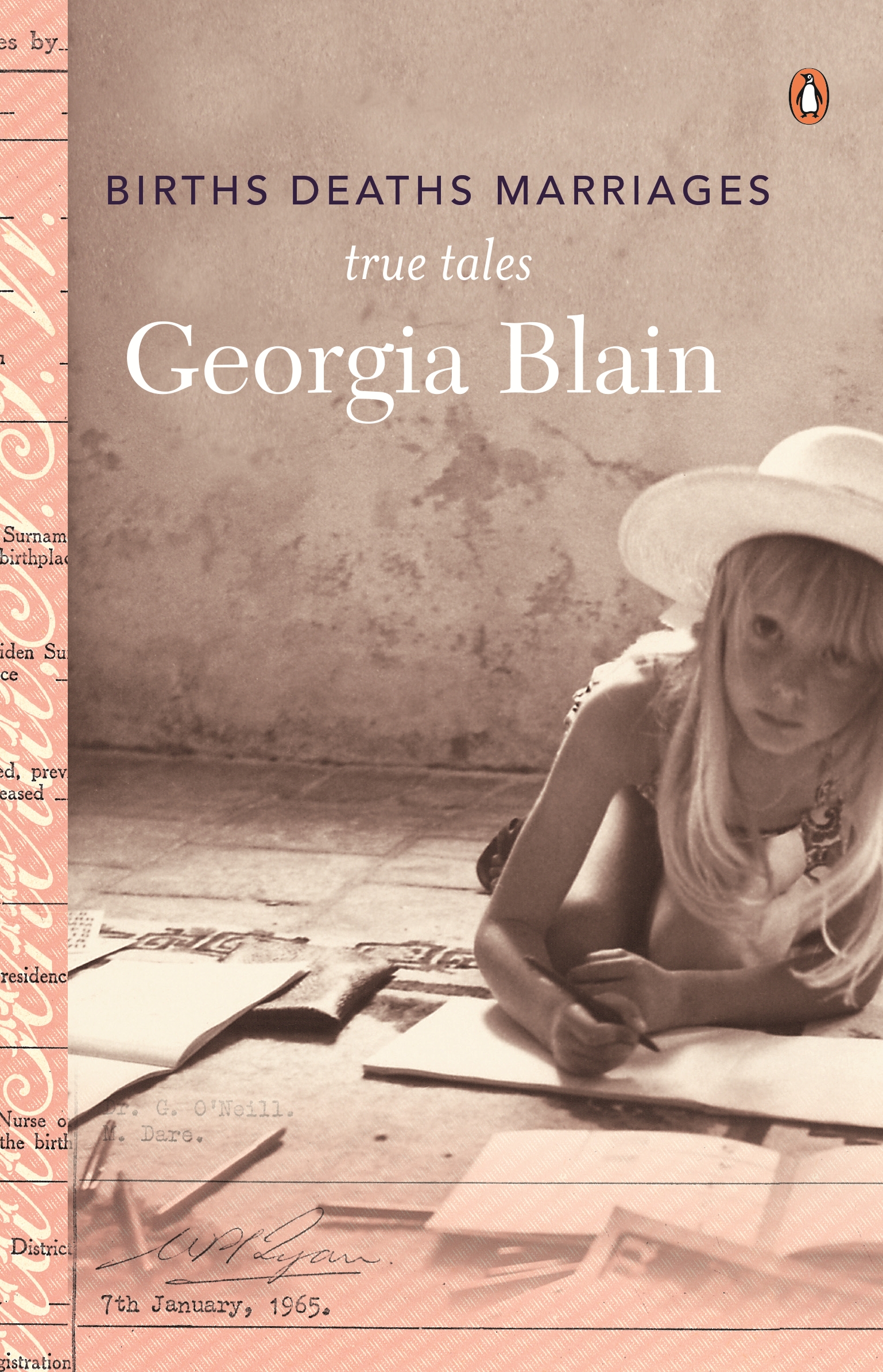

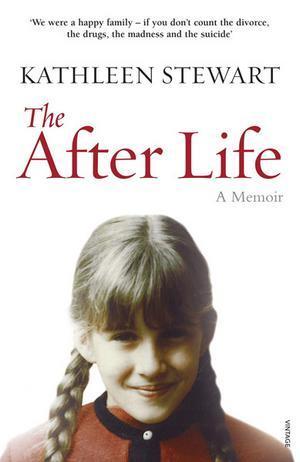

- Book 2 Title: The After Life

- Book 2 Subtitle: A memoir

- Book 2 Biblio: Vintage, $34.95 pb, 294 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

Births Deaths Marriages is made up of fourteen autobiographical essays, six of which have appeared previously. The first essay, ‘A Room of One’s Own’, recalls Blain’s childhood with her brothers Jonathan and Joshua and her mother, the writer, broadcaster and feminist Anne Deveson. The family is dominated by an emotionally volatile father, the broadcaster Ellis Blain, whose presence alone, according to his daughter, created fear and tension. Obsessed with order, he would ‘darken with rage at a mark on a wall, crease in a sheet or crumb on the floor’, his violent flare-ups alternating with periods of depression and despair. He shut himself away from children, pets and the messy world in a spacious room with a Chinese carpet, obsessed with its spotless white border. Deveson, meanwhile, wrote in a cramped alcove next to the kitchen, with the children at the door begging for attention. Throughout the memoir, Georgia Blain longs for a room (a life, a career, an escape from the family) of her own.

The episodic structure allows for comment on a number of related issues: a period at the mercy of a Maoist teacher; the peripatetic life Blain lived with her mother after the break-up of the family; her father’s death from cancer when she was sixteen, and her own, often unhappy, relationships. ‘The Germaine Tape’, besides bringing up the issue of feminism, provides another glimpse of the father. Blain tells of replaying the tape of Ellis Blain interviewing Germaine Greer. His attitude towards women is painfully embarrassing, and he is no match for Greer. She has just been flaunting the menstrual blood on her skirt: ‘“Look,” she said with delight, pointing it out to everyone in the room, and sure enough, there it was.’ This is a rare moment of humour in an all-too-serious memoir.

The essays always circle back to the central concerns: life under the shadow of the father, the mental illness of the elder son, Jonathan – treated in detail in Anne Deveson’s Tell Me I’m Here (1991) – and the terrible effect on the whole family, especially the narrator. Diagnosed with schizophrenia at seventeen, Jonathan lived rough on the streets among drug addicts and the homeless, and suicided in his twenties. There is a moving moment when, in his teens, after a nasty quarrel with Georgia, Jonathan breaks down: ‘Don’t be like me ... I’m so scared of what I am ... I’m not normal.’ Pathetic, too, is the glimpse of the young Georgia trying to study on one level in the Adelaide house while Jonathan and his friends, ‘young men in varying states of madness, all with matted hair ... and eyes that failed to focus’, crowded the basement below.

These elegantly written and moving essays give us another perspective on schizophrenia, apart from that provided by Anne Deveson. The positive force running through the memoir is Georgia Blain’s determination, against all odds, to write, to find that life, that room, of her own. There is, as well, her positive relationship with her mother and her daughter, Odessa. We gain a sense of the ‘ceaseless unfolding’ of the female generations, pictured in one place as a continuous bolt of cloth, ‘softly thumping on the table as it is rolled back to reveal more of a pattern that will repeat itself, with minor variations, over and over again’. This is an image to live by.

DROPCAP

There are few positives in The After Life: A Memoir. Kathleen Stewart, a writer with seven novels to her credit, turns to memoir to vindicate her life. She details her sustained abuse at the hands of her family and sundry predatory males, some disguising themselves as lovers, and rejects the blame and self-blame that she has been subject to for over forty years. The writing is fluent and stylish, swept along on a tide of indignation and scathing humour. ‘We were a happy family,’ she writes, ‘if you don’t count the divorce, the drugs, the madness, and the suicide.’

Stewart’s father is an apparently respectable North Shore businessman. Her mother is beautiful, petite and beguiling; the older brother disappears whenever possible. As a child, Stewart is whipped, as a teenager verbally abused, and the whole family is constantly threatened with ‘anger that pours from his mouth and body like flames’. Here is Stewart’s father letting loose a stream of filth at the breakfast table: ‘You bitch, you lousy stinking bitch’, ad infinitum. The mother has merely put the butter in the wrong compartment in the fridge, and ‘the soft butter is not soft enough for his toast. The soft butter is hard.’ Meanwhile, the mother’s attitude oscillates between smothering love and stinging ridicule. Both parents are seen as inhuman, almost caricatures. He is a ‘relentless stalking beast ... who rampages still in some far dungeon in my psyche’; the mother is ‘a butterfly with brightly coloured wings’, but as ‘malevolent as a hunting spider’.

The family house has, according to Stewart, been built ‘brick by brick with frozen blood, each room carpeted with threats of death, each wall blasted white with rage’. She enters it through an ante-room bristling with lethal weapons collected by her father – ‘the cannon, the rifles, the swords, the battle-axe, the guns and disembowelling knives’ – and exits through her bedroom window by night whenever she can. By the time she is fourteen, she has become a nocturnal animal, riding the trains, roving the sleeping suburbs with a school friend, experimenting with drugs, seeking and finding danger.

The account is centred on her final school year in 1976, by which time Stewart has become a confirmed victim. At thirteen, she was molested in her bed at night by a naked relative and blamed for it by her mother. At fourteen, she was brutally raped by a bikie, and blamed herself for putting herself in his way; and in the year in question, she was creeping from home at night to join her lover Martin, a self-seeking, on-again-off-again tormentor. They surf the roads at night in his Italian sports car, making delirious love, dealing drugs in the Cross, returning at dawn so she can resume some sort of a daytime life. Her self-blame when Martin ill-treats her establishes a pattern in her future dealing with men which lasts into her forties. Perhaps the title The After Life suggests that her life will now change. Meanwhile, by the end of 1976, two of the family members have attempted suicide and one has succeeded: ‘With hindsight, I think the cat should have been quietly put down. But in the end two of the three of us ... thought it a better plan to put ourselves down instead.’

The writing is literally fabulous as Stewart resorts to the archetypes of folk- and fairy tales – their cruel creatures and moral absolutes – to convey her distress. The father is a fire-breathing dragon who spreads desolation; the mother is a spiteful shape-changer; the child is like Gretel, lost in the desolate woods. At another time, she is the little mermaid, her body cruelly torn and split by rape. The writing is wonderfully atmospheric: the dreamy half-drugged delirium of the love affair with Martin; the weird psychotic world of the Cross; the descriptions of the nocturnal world in which the child, the existential outsider, wanders while the whole world sleeps. This is writing of the highest order.

Comments powered by CComment