- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Custom Article Title: Nolan and insolence

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Nolan and insolence

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

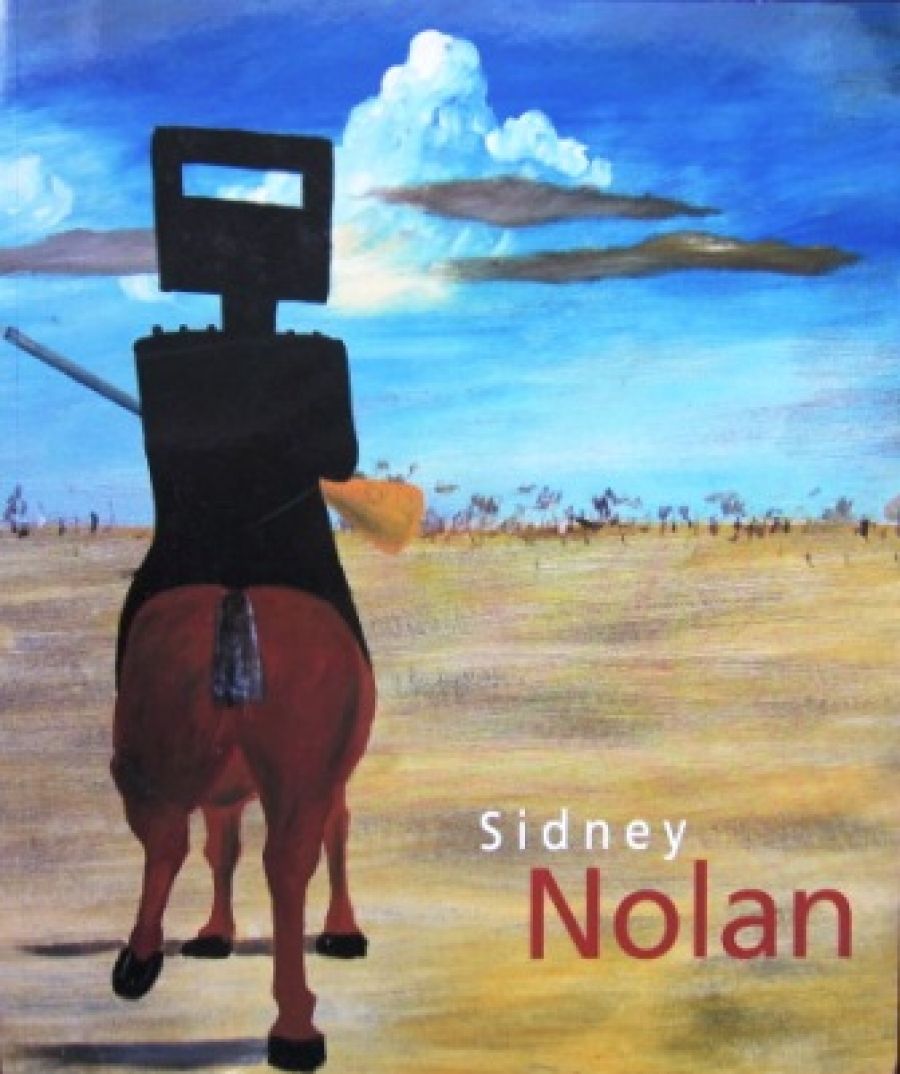

Sidney Nolan’s Ned Kelly (1946), and the Ramingining artists’ Aboriginal Memorial (1988), are the only two Australian works in a new and highly commercial picture book, 30,000 Years of Art: The Story of Human Creativity across Time and Space. The Ramingining installation of 200 painted hollow-log poles, the kind used as containers for human bones, was categorised as ‘Aboriginal Culture’. Nolan’s painting was categorised as an example of ‘Surrealism’, but the caption concluded, sensibly, with the concession that he was more than a Surrealist: ‘Ultimately Nolan never adopted a single idiom, instead exploring different moods and techniques to portray his themes of injustice, love, betrayal and the enduring Australian landscape.’

- Book 1 Title: Sidney Nolan

- Book 1 Biblio: AGNSW, $85 hb, $69.95 pb, 272 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Although the choice should not suggest that Nolan is Australia’s only world-quality artist, it does suggest that he might be considered one of our most characteristically ‘Australian’ artists, and possibly the best of all our non-indigenous artists. On both counts, Fred Williams, John Brack and Robert MacPherson might be equal contenders, but there is certainly a case for Nolan. When the Art Gallery of New South Wales presented his first big retrospective exhibition, by its then director, Hal Missingham, and then toured it to Melbourne and Perth in 1967, various students throughout Australia were astonished by such inventiveness, insouciance and wit in a local painter, and resolved that they too might forget the Australian cultural cringe and live dangerously. Nolan has been a creative example. He died in 1992, after a heyday around forty to sixty years ago. His art is settling into focus.

The recent AGNSW exhibition of Nolan’s paintings, by in-house curator Barry Pearce, generally confirms the excellence of the work, but downgrades certain phases: no Gallipoli series, no Oedipus, no Eureka stockades, no Auschwitz ovens, no Adelaide lady heads. The latter wore make-up and respectable hats for town to become, in the 1967 retrospective, ‘masked’ female counterparts to the masked Kelly in the bush; in the new retrospective, they should have been contrasted with the unkempt hairy maleness of the Pilbara miners’ heads. Pearce upgrades the biblical subjects, the Australian drought carcasses, the Kelly and Burke & Wills portrait heads, the African animals who contemplate beauty, the serious and self-reflective 1950s Kellys, the heaving red Australian deserts and blue Antarctic ice-fields. He makes a fairly convincing case for the late spray-gun Chinese river-and-mountain landscapes that nobody has admired much except sinophile Edmund Capon. Towards the end, we float past not only the marvellous nine-panel Riverbend I (1964–65, Australian National University) but also its only slightly varied replica Riverbend II (1965–66, News Corporation). The two Riverbends are by no means too much of a good thing, though certainly a self-indulgence for both the curator and the exhibition visitor.

In the interest of a fairly seamless exhibition experience, and one of manageable size, we see none of the crisply tendrilised drawings and no book illustrations. Nolan’s own shocking Paradise Garden poems – issued in 1971 in a limited edition of only eighty-five – is crucial if we are to understand as well as enjoy the oeuvre. There are none of the few sculptures; no evidence of the huge foyer decorations, accumulations of up to 800 small paintings of flowers; little evidence of the large theatre sets. (Though absent from the exhibition, these topics are touched on in Pearce’s catalogue.) And in this cunningly easy-viewing and indeed quite blissful immersion in a paintings-only exhibition, of 117 works, there was room for only ten of the twenty-seven canonical first Kelly series; connoisseur Pearce would also say they aren’t all good enough.

Similarly absent are several unchallenged favourites, such as the NGA’s Head of soldier (1942), the National Gallery of Victoria’s two Dimboola workmen, the Railway guard and the Flour lumper (both 1943), and the same collection’s various St Kilda Baths Bathers (1942, 1943, 1945). In one of the last, boats are burning out on Port Phillip Bay; it would have made a nice companion to the St Kilda Palais de Danse on fire, watched from Luna Park by a heartless crowd, including nine-year-old Sid, out to enjoy the spectacular ‘entertainment’. Another among the later Kellys should have been Death of a Poet (1954, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool), based by Nolan on one of the plaster-cast death masks taken from the celebrity corpse in 1880 and offered for sale in Melbourne; that painting was a delight within the previous Nolan retrospective, by Jane Clark, produced in 1987 by the NGV, and it also emphasised Nolan’s creative engagement with Australia’s low-level commercial popular culture.

The big exhibition catalogues published by art museums are usually the best art books. They put first things first: great quantities of high-quality colour illustration. They contain fresh research and fresh interpretation. (Recent examples are Jules Bastien-Lepage, from the Musée d’Orsay, Paris, and Patinir and Tintoretto, from the Prado Museum, Madrid.) Barry Pearce’s Sidney Nolan is another outstanding example of an exhibition book.

However, for easily accessible high-quality illustrations of the complete first Kelly series, it is still necessary to consult T.G. Rosenthal’s Sidney Nolan (2002, Thames & Hudson), a monograph that also has chapters on the artist’s work in mediums other than painting, that displays on its back jacket the Railway guard, Dimboola, ignored by Pearce, and that includes the transgressive 1942 Latrine sitter army paintings, also ignored. Jane Clark’s 1987 exhibition book fully illustrated over 150 works, but with rather small, meaner images, many of them black-and-white; some works were less than excellent but made good art-historical points; the book design was rather confusing; the scholarship attached to each catalogue entry was detailed and informative. Pearce’s new book is likewise a complete record of his exhibition, but lavish, with all illustrations in colour and large in size; the design is pleasing and the layout easy to read; but the catalogue entries, beyond mechanical listings of provenance, exhibition history and references in the literature, contain no extended explication of the kind that Clark provided. Instead, Pearce embeds the complex details inside his thirty-page essay.

There some puzzles remain unattended to. Why include the unappealing oddity landscape Boats (c.1945) at all? Where is the scene? Is it Ocean Grove beyond Geelong, where Nolan lived for a while with his first wife, Elizabeth Paterson, before being sucked into John and Sunday Reed’s circle at Heide, outside Heidelberg? Why does the diagonal shadow falling onto the foreground from an unseen figure contradict the horizontal shadows cast by four boats levitating above the sand? Well, since we are given plenty of useful corrective, from Nolan’s own words, that he was just as much concerned with modernist abstract flat form as with mythology or Australiana, we can eventually guess that the three horizontal bands of sky, sea and sand were a good abstract structure on which to suspend the striped boats, and that maybe the real-life diagonal jetty demanded an opposing diagonal and called into existence an imaginary, out-of-kilter shadow. The shadow might also signify Nolan’s appreciation of the photographers’ shadows that appear unbidden and weirdly ghost-like in many amateur snapshots. It reminds us, certainly, that Nolan often copied old photographs for his Kelly and explorer portraits, and that for landscapes he often raided the Australian travel magazine Walkabout of his own day: in the Kelly series, The watch tower uses a Walkabout view of Longreach in outback Queensland, a very long way from Kelly country in Victoria. In black-and-white photographs, the tones are already simplified, a short cut to tonal truth in a painting.

The general look of faux-naïveté in Boats probably signifies appreciation of similar work by the British modernist Christopher Wood, whose paintings Nolan would have seen in an exhibition that came to Melbourne in 1937. And the stripes on the boats, and a dotted flight of birds in the sky, reiterate what we have already noticed: stripes and dots occur everywhere in Nolan’s art, just as they do in the art of Picasso and Matisse, and in present-day Aboriginal painting. Stripes and dots are a simple and very effective way to vitalise a composition, to make it shimmer and glow. Nolan’s convicts wear stripes. His policemen are dotted with brass buttons. The Riverbends contain tiny Kelly and policemen figures, but the paintings are chiefly a matter of stripes and cross-hatchings transformed into tree trunks.

Since Pearce’s essay makes much of Nolan’s early indecision between poetry and painting and his particular admiration of Rimbaud – Sunday Reed ruled that he should choose painting – perhaps the levitating vessels in Boats are there to remind us of Rimbaud’s most famous poem Le Bateau ivre (‘The Drunken Boat’). Later in life, Nolan did not himself go in for drunken derangement of the senses; once, at the bar in the Chelsea Hotel, New York, I noted that he drank lemonade, remained observant and cool. But perhaps back at Heide with the Reeds he drank whisky.

A further unexplained puzzle is another at-first-sight unappealing painting. Bather in lily pool (1957) is displayed in the exhibition as if it were a companion to three Leda and swan paintings (1958–60). Its rough, crusty surface is much cruder in actuality than in the catalogue illustration – which precedes illustrations of four rainforest swamplands haunted by tiny figures of the naked Mrs Fraser and her convict – and very different from the sleek scrapings of the Leda and swan paintings beside it in the exhibition. It shares with the swan paintings the same red stains of blood, but also has white-paint handprints, perhaps pressed onto the image by a rapist. Bather in lily pool is obviously a transgression against the French charms of Monet’s lily pools, and even more extreme when we recognise vaginal blood in the water.

Ned Kelly death masks were part of Melbourne’s popular culture. So was the Ned Kelly story, still alive long after 1878–80. Nolan spent six years in the 1930s working in commercial art, and therefore became skilled at unorthodox techniques of collage, scraping, tracing, spray-guns, at improvised mediums such as his frequently used Kiwi brown boot polish, and at working fast. His workplace was Fayrefield Hats, and his second wife, Cynthia Reed, liked to say that was the jumping-off point for his Ned Kelly helmet-mask, a kind of hat. There had been earlier Ned Kelly movies, and one wonders if the Kelly story persisted in vaudeville turns at the Tivoli, Melbourne’s theatre for agreeably vulgar music hall performances, and whether Nolan frequented the Tiv.

The carefully selected sequence of twenty-seven Kelly paintings that Nolan exhibited in 1948 had nothing to do with the sequence of their making; he arranged them as a theatrical entertainment. First came a dead calm flat landscape, a golden dawn rising through gum trees. The second painting was the startling high-noon Ned Kelly that Phaidon selected for its 30,000 years of art and that the AGNSW selected as the cover image for Pearce’s exhibition book; it is a direct rear view of horseman Kelly, and since the horse is only a headless rump and four legs, we see nothing resembling a mythical Greek centaur, more a comical music-hall four-legged dancing man. There is a seduction scene, Constable Fitzpatrick and Kate Kelly (in which another splendid hat, the constable’s helmet, is jokingly lined up with a same-silhouette clock on the kitchen mantelshelf); a disguised bushranger Steve Hart dressed as a girl; the womenfolk’s bizarre industry of Quilting the armour; the flying acrobatics of both horse and policeman in Death of Constable Scanlon; a wedding; an under-the-bed concealment; gender confusion in Bush picnic, when the out-laws got a policeman drunk ‘and Ned Kelly took the merry constable as his partner in a buck set’; a naked man surprised bathing in a dam. After the Glenrowan shootout and conflagration, we see a climactic chorus-line of policemen, into which a naked black-tracker is inserted, his dotted and striped scarifications and pubis rhyming exactly with the elaborate dottings of policemen’s buttons. And finally, in The trial, judge and outlaw glare sombrely at each other and vow to meet in the hereafter. Nolan later immersed himself in opera, but the Kelly series is more like vaudeville.

Nolan’s work has been taken to ‘represent’ Australian-ness, and certainly the observation of landscape and temperature in The burning tree and Morning camp is magically exact. But personal qualities and transformation, not ‘representation’, are what make art significant. Elwyn Lynn’s book Sidney Nolan: Myth and Imagery (1967, Macmillan) preceded the 1967 AGNSW retrospective, whose catalogue, typical of the time, was only a slim forty-page pamphlet. Lynn quoted the following comments made in 1964 by Edward Lucie-Smith:

One is struck by the extent to which the Kelly paintings are wilful, personal, capricious … [They] seem to have been judged far more solemnly than need be or, I suspect, than the artist intended … but what is most memorable about them is their insolence – the way in which an artist seizes upon a cherished national myth and turns it to personal, introverted ends … is exhilarating ... The Australian hunger for national identity has over-ridden Nolan’s delicate ironies …

Nolan himself in 1947 said something teasingly similar: ‘Whether or not the painting of such a story demands any comment on good and evil I do not know. There are doubtless as many good policemen as good bushrangers.’ Insolence was a fine insight. Rimbaud sent his Bateau ivre to Verlaine in 1871 by way of introduction, and they embarked on a wild and scandalous love affair. Nolan coolly told Elwyn Lynn that Howard Matthews, whom he loved dearly, was his Verlaine; Kate Hattam believed Nolan ‘swung both ways’. His terrible self-loathing Paradise Garden poems and drawings are about the ménage à trois at Heide, and rancorous about Sunday Reed for doing him wrong by remaining with her husband (and for keeping the Kelly series of paintings); he hits at her ‘desiring fête champêtre / with a trapped smile, / steeled by noon whisky / I enter her old plumbing’. In the another of the poems, ‘Buddha came from the bush / [...] he rubbed old men / in the baths / until they were strong enough / to penetrate their private / secretaries’. Barry Pearce’s exhibition book illustrates photographs of what looks like a self-consciously sexpot young Nolan, and somewhere (I think it was in the exhibition audio tour script) tells us that John Reed was ‘asexual’. We don’t really need to know so much, but Pearce’s essay, with its fresh interpretative emphasis on Rimbaud and poetry, at least reminds us that Nolan not only strolls us through the opalescent beauty of Australian landscape but also makes us stalk the wilder shores of love.

Comments powered by CComment