- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Non-fiction

- Custom Article Title: Chairman Rupert

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Chairman Rupert

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

For two decades of my life, I worked as a senior executive with first Rupert Murdoch and then Kerry Packer. These were challenging years, not without their hairy moments, but I always felt my best way of retaining any kind of perspective at that time was to conceive of myself as a bit player at the court of a seventeenth- or eighteenth-century monarch

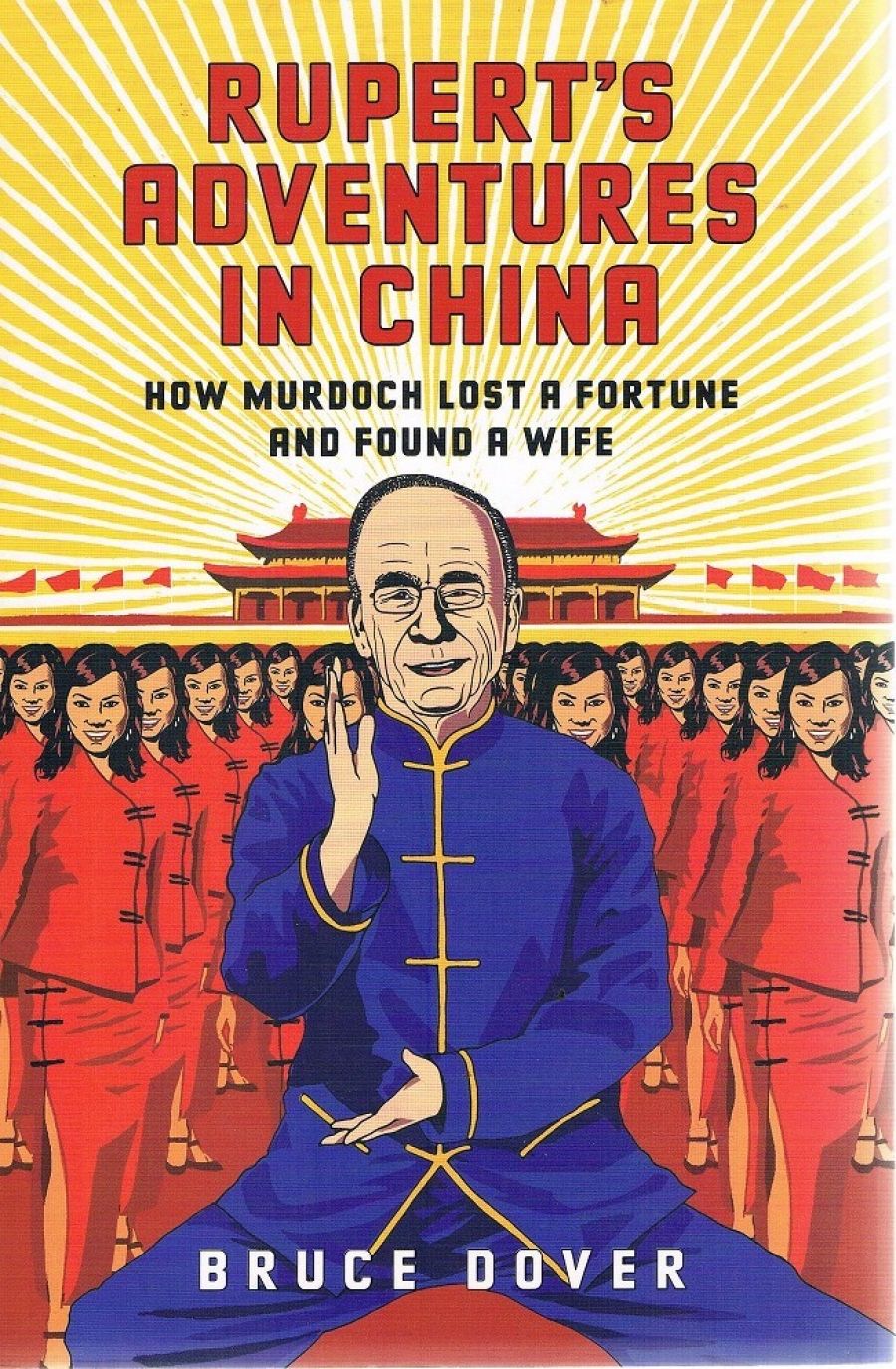

- Book 1 Title: Rupert's Adventure in China

- Book 1 Subtitle: How Murdoch lost a fortune and found a wife

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking, $32.95 pb, 302 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

In the early 1990s everyone in the media became excited by the general prosperity that had then been achieved by the Four Tigers – Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan – and by the possibility of establishing thriving new businesses there. But even though the transformation of the economies of India and China had barely begun, these two countries were seen as the ultimate glittering prizes, particularly after the Asian meltdown deprived the striped cats of much of their roar.

Fresh from making hay in the newly liberated Eastern European sunshine, the moguls were on the prowl. Murdoch, in particular, was determined to get his foot in the Chinese door, having acquired Hong Kong’s South China Morning Post as far back as 1987. Having experienced his near-death business crisis in 1991, and survived it, and having merged the potentially fatal loss-maker, the UK’s Sky Television, with its rival, British Satellite Broadcasting (BSB), to create the immensely profitable BySkyB – demonstrating once again what fun can be had in commanding a monopoly – he must have felt invincible. He certainly felt strong enough in 1993 to acquire Richard Li’s STAR TV for what seemed at the time like too much money (the underbidder was Pearson, whose book operation is the publisher of this book). Murdoch was raring to take China by storm. But, as Dover tells it, his Long March ultimately ended in a rout equivalent to that which drove the Kuomintang to their Formosan redoubt. His misadventures along the way were almost Shakespearean in their dimensions – fatal flaws aplenty – and only alleviated by the blossoming of the Great Romance (enter Wendi Deng).

What Murdoch ideally needed were the proverbial Chinese Walls, which would have allowed him to whisper sweet nothings into Beijing’s ears that could not be heard elsewhere and likewise speak his mind elsewhere without fear it would be blown back to the ears of those he was wooing. While politicians customarily master the dark art of dog whistling, this is not so easily achieved by a high-profile media mogul.

What the Chinese leaders wanted to hear was that Murdoch respected their culture, which was code for him affirming his indifference to the fate of the Tibetan people or the Falun Gong or the small matter of human rights in the Middle Kingdom. For Murdoch, this was not too great a leap. In 1999 he confided to his biographer William Shawcross (and thus to a few billion interested bystanders) that he held little sympathy for the Dalai Lama: ‘I have heard cynics who say he’s a very political old monk shuffling around in Gucci shoes.’ He was never exactly the kind of media proprietor who was prepared to go to the barricades to defend the rights of his employees to say what they liked, particularly if it was adverse to his own interests.

Yet there were problems. Theoretically, Murdoch had guaranteed the editorial independence of The Times when he acquired it in 1981; but the Chinese had a particular aversion to Jonathan Mirsky, the Times’s East Asia correspondent, based in Hong Kong. Worse, senior executives at his book operation, HarperCollins, had paid a large advance to the last British governor of their Chinese colony, Chris Patten, for his memoirs and did not seem to get the message that Murdoch wanted this book killed.

In truth, Murdoch was no more wedded to freedom of speech among his people than the Chinese authorities were, but he never had to consider rolling out the tanks. In a very judicious passage, Dover writes:

The thing about Murdoch is that he very rarely issued directives or instructions to his senior executives or editors. Instead, by way of discussion he would make known his personal view-point on a certain matter. What was expected in return, at least from those seeking tenure of any length in the Murdoch Empire, was a sort of ‘anticipatory compliance’. One didn’t need to be instructed about what to do, one simply knew what was in one’s long-term interests.

Murdoch famously canned the Patten memoir, but in truth his earliest problems were entirely of his own making. In a notorious speech delivered in London in September 1993, Murdoch vehemently declared:

Advances in the technology of telecommunications have proved an unambiguous threat to totalitarian régimes elsewhere. Fax machines enable dissidents to bypass state-controlled print media. Direct-dial telephony makes it difficult for a state to control interpersonal voice communications. And satellite broadcasting makes it possible for information-hungry residents of many closed societies to bypass state-controlled television channels.

The chapter in which Dover explores the earliest repercussions of these thoughtless remarks is called ‘Whoops’ (his account is enlivened by a veteran newspaperman’s choice of chapter headings and cliffhanger chapter endings). Whoops, indeed. The Chinese in response basically made it illegal for any of their private citizens to own a satellite dish and for many years froze Murdoch out of meaningful contact with their higher echelons, while his archrivals, Time Warner and Viacom, seemed to be making significant progress. Bruce Dover tracks Murdoch’s uncharacteristically patient attempts to undo the damage created by this self-indulgent lapse into telling the truth. Most notably, he attempted to curry favour by wooing Jiang Mainheng and Ding Yucheng, respectively the sons of President Jiang Zemin and Ding Guangen, the head of the State Propaganda Department. In his efforts, he was assisted by what Dover describes as ‘Murdoch’s absolute pragmatism, which puts money before any moral ideology’.

However pragmatically, the media baron had both a great victory and then a great defeat. After years of pandering and repeated knockbacks, he finally achieved one of his principal goals – a personal meeting with President Jiang. Past experience had made him confident that his charm and charisma could achieve a great deal in such high-level one-on-one conversations. But, alas, by now President Jiang was almost at the end of his reign and, with the succession of President Hu Jintao, Jiang and his somewhat venal Shanghai clique – people whom Murdoch had wooed tirelessly and at great expense to his stockholders – were swept away into realms of feeble influence. The mogul suddenly found himself back at Beijing’s version of Old Kent Road.

If this is the major leitmotif of Rupert’s Adventures in China, the rise and rise of Wendi Deng provides the somewhat lighter motif. Dover does not embrace the nonsense that Rupert married Wendi to further his imperial ambitions, nor does he succumb to other paranoid fantasies, such as that she is a Chinese spy. The strength of his book is that the author, who ultimately fell out with Murdoch after accompanying him on much of this journey, keeps his feet on the ground throughout. While he does not entirely conceal his glee at the failure of the Internet venture, ChinaByte, or when recalling the hundreds of millions of dollars urinated up against the Great Wall by James Murdoch, he never allows malice to distort his perspective.

He is almost certainly right in concluding that Murdoch could not have, and would not have, acquired the Wall Street Journal and given its staff assurances of editorial independence, as he had previously done at The Times, if he retained lingering ambitions in China. He could not have juggled the WSJ’s brutal candour with being an avowed apologist for the Chinese government. In fact, it had been the WSJ’s deputy features editor, Tunku Varadarajan, who had once labelled Rupert ‘a master practitioner of the corporate kowtow’.

Murdoch continues to enjoy great success in India. As Dover concludes, here is a mogul who is most successful in vibrant democracies, where the political leaders become subjugated to him because of their real fear of his power to sway their masses. For the Chinese leadership, there was no downside in thwarting Murdoch’s ambitions, but, in the end, despite all their best efforts to obstruct him, he did have an enormous and lasting influence on their nation’s popular culture. His minority partnerships and competitive manoeuvrings resulted in the Chinese television industry virtually robbing him of his intellectual property and creating successful local knock-offs of his most notable American programmes.

Dover’s conclusion is ultimately a tribute to his former boss’s amazingly transformative influence on global media:

As in virtually every country in which the media baron has operated, Murdoch has been an extraordinary catalyst of change in China. In the same way he took on the Fleet Street unions and turned the British newspaper printing business on its head, and launched satellite television in the UK and established the Fox Cable network in the US, Murdoch’s coming to China galvanised the Beijing leadership and set in train a transformation of its formerly staid, conservative media sector.

I doubt Rupert would be satisfied with leaving such a wonderfully philanthropic legacy in the Middle Kingdom, but perhaps one day the Chinese Communist Party will raise a statue of him somewhere prominent and finally provide public recognition of him as one of their eternal inspirations.

Comments powered by CComment