- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Journalism

- Custom Article Title: Unlikely hero

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Unlikely hero

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

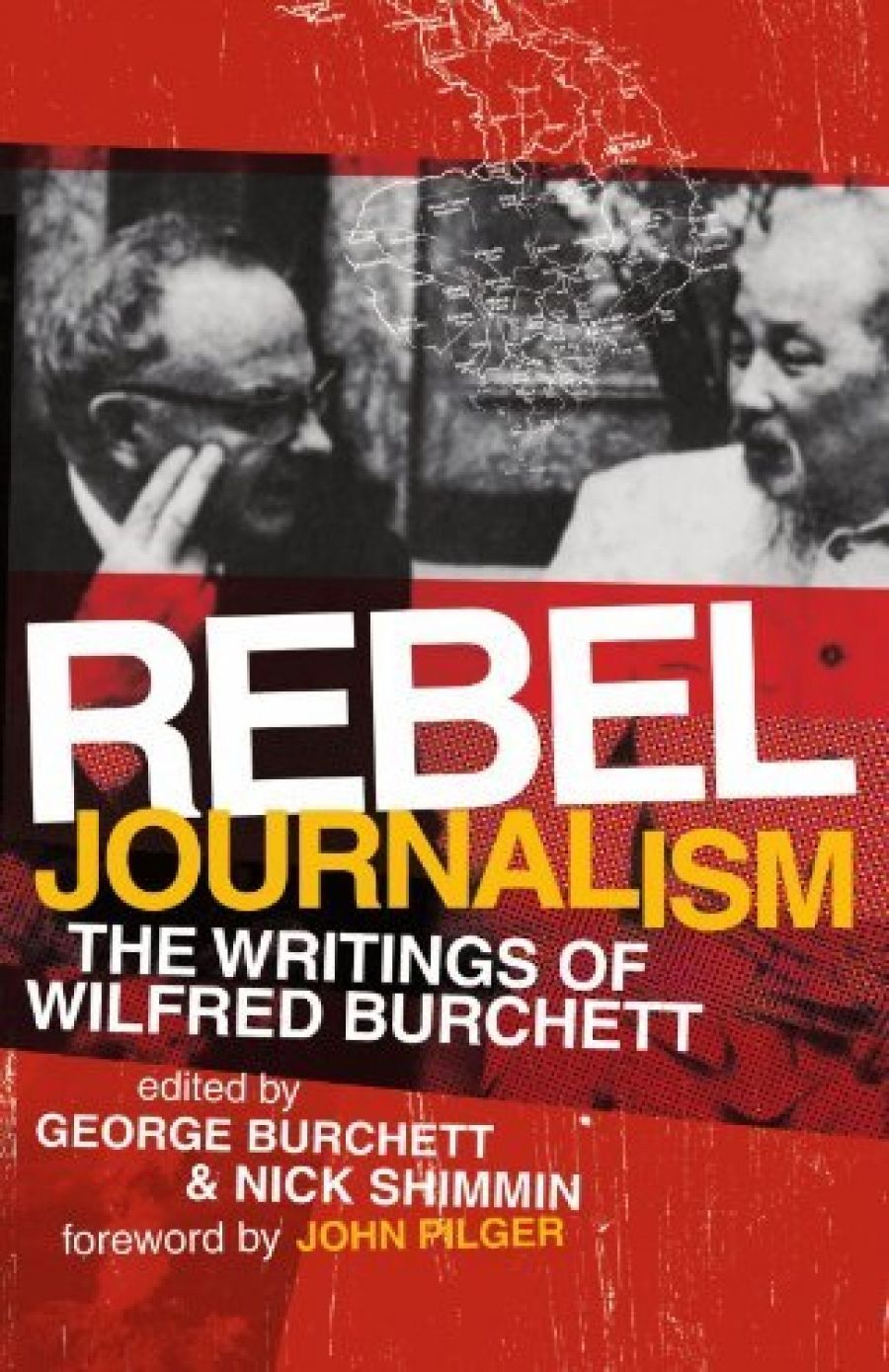

Though he died a quarter of a century ago, the life and career of the Australian-born reporter Wilfred Burchett (1911–83) continue to attract significant critical attention. On the heels of Tom Heenan’s political biography, From Traveller to Traitor: The Life of Wilfred Burchett (2006), and Burchett’s re-released autobiography, also edited by Burchett’s son George and Nick Shimmin (2007), comes this collection of Burchett’s writings, spanning much of his long, eventful career.

- Book 1 Title: Rebel Journalism

- Book 1 Subtitle: The writings of Wilfred Burchett

- Book 1 Biblio: Cambridge University Press, $39.95 hb, 308 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Unlike the supine media, which botched their reporting of the Iraq War because they were ‘embedded’ with the occupying forces, Burchett eschewed official escorts, alert to governments’ vested interest in diverting journalists from their revelatory duties. This determination to slip the leash allowed him to break some of the great stories in twentieth-century journalism. Most notably, Burchett was the first Western journalist to breach the security cordon around Hiroshima to inform the world about the ‘atomic plague’ afflicting survivors of the bomb. Less than a decade later, he exposed the American Army’s use of germ warfare and Allied mistreatment of POWs in Korea. These two scoops alone distinguish Burchett as Australia’s most influential and important reporter.

Burchett’s personal and professional qualities should, by rights, have made him an Australian hero. As fellow Burchett biographer Gavan McCormack remarks, who has ever more thoroughly exemplified the prized national characteristics of ‘independent mindedness, multiculturalism … pragmatism … and [unwavering support] for the common man and the underdog against authority’? However, for the succession of Coalition governments that ruled Australia from 1949–72, Burchett was a figure of unmatched loathing. Conniving with the American government, they accused Burchett of working for Chinese and North Korean Communists, and of bracing Allied POWs to induce false admissions of engaging in biological warfare. For more than fifteen years, the Australian government deprived him of his birthright, a passport and citizenship for his children born outside Australia. This flagrant breach of Australian law and of the Universal Declaration on Human Rights was once fatuously excused by then Immigration Minister Harold Holt on the grounds that Burchett’s prolonged absence from Australia rendered him not ‘a constituent member of the Australian community [but] an “immigrant” despite his possession of Australian citizenship’. As Heenan has observed, the government’s prosecution of Burchett served two functions: to deter the reporter from returning to Australia and, more importantly, to prevent the Australian public from asking whether Western governments had a case to answer in relation to their conduct of the Korean War.

Damning allegations against Burchett, nevertheless, have died hard among rival journalists and academics, even if the truculent refusal to re-examine Burchett’s alleged treachery is a peculiarly Australian phenomenon. After all, Burchett was held in sufficient respect – for his high-level contacts (with figures such as Chou En-lai and Ho Chi Minh), his political knowledge of Asia and his reliability as a two-way messenger – to be consulted by Henry Kissinger, then secretary of state, about policy directions for Vietnam. The fact that significant Australian cultural ‘gatekeepers’ maintain their anti-Burchett rage raises interesting questions about Australian politics and society.

Burchett addressed these questions himself when he remarked to John Pilger that he had the qualities, particularly an open mind capable of revising prior convictions, that made him a stark threat to those governments that refused to revise (misguided, erroneous or obsequious) foreign policy positions, and to the media interests that continued to parrot rather than question these positions. In Hiroshima, where Burchett’s discoveries made obsolete hitherto carefully manufactured American propaganda, and in Korea, where he again dared to break the ‘infamous conspiracy of silence on germ warfare’ perpetuated by ‘Western pressmen’, Burchett proved he could undermine, if not shatter, the West’s notion of itself as the better party in the conflicts of the age.

Yet it remains puzzling why Burchett’s claims about Western conduct in war and diplomacy continue to be so vehemently challenged. During the Korean and Vietnam wars, the notion of Western virtue had real currency. Now we know that Nixon carpet-bombed Cambodia, the American Army deliberately exposed its own servicemen to nuclear fallout and the Australian government did the same to Aborigines in Maralinga. If anything, Burchett’s writing confirms that, however much things change, the more they stay the same. His reports of germ warfare in the Korean War chillingly prefigures both Vietnam and Iraq: the former through the bombing and napalming of mud hut villages, the latter through the ‘democratic liberation’ of a people by the destruction of their homes and cities (along with the dropping of swarms of plague-infected insects on their villages and fields).

If Burchett’s only sin had been to expose war crimes of the West, he might now be more celebrated, but his enthusiastic support for counter-revolutionary activity in Europe after World War II made this impossible. For Burchett, politics was deeply personal; he chafed at the Allied, capitalist domination of Europe and of the restoration to power and influence of the old Establishment. These personal convictions were evinced in visceral responses to reactionaries such as the Hungarian Cardinal Jószef Mindszenty, whom Burchett likened to a school bully who, when ‘faced with his superior in weight and punch power’, behaves with ‘shame, defiance, fear and [an] appeal for mercy all at the same time’.

In the case of Mindszenty, Burchett’s moral and political radar was true. But his gullible support for central European communist régimes revealed a romantic naïveté. While he presciently observed that central Europe was chiefly a strategic prize for the United States, and ‘democracy’ a rallying cry for new empire, he checked his realpolitik at the door when he saw ‘an alliance of workers, peasants and intellectuals’ at work in the new republics of Bulgaria, Yugoslavia and Hungary.

Beyond Australia’s shores, Burchett’s reputation recovered from this lapse of judgment as he continued his remarkable career in South-East Asia. Winning the confidence of generals and political leaders across the region, his interviews with men such as former North Vietnamese Foreign Minister Nguyen Duy Trinh became the basis for diplomatic negotiations at the highest levels.

This is all a matter of history. The general reader today may want to know if Burchett’s writing style remains as involving as his exploits were significant. Certainly, Burchett has a direct, engaging style that emphasises detail and colour, but not at the expense of economy and momentum. He can connect the reader with any subject of his choosing, even some that many readers would not readily inquire about (iron fields in New Caledonia, for example).

As his description of Mindszenty suggests, Burchett could indulge in propaganda; his 1951 diatribe about central European ‘kulaks’ saw him adopt a pernicious Soviet appellation to disparage a whole class of people: allegedly wealthy, counter-revolutionary peasants, whom he accused of lusting for lucre at the expense of all other social causes.

Nevertheless, Burchett and his supporters claim that he had the integrity to disavow objectionable beliefs and associations which he subsequently had cause to regret. They also point to his faith in the ideals and actions of the little people whom he never ceased to champion, including the people of Vietnam and the second- and third-generation victims of atomic radiation in Hiroshima, the hibakusha, ‘the most stalwart and militant of peaceniks’.

The general reader might draw his or her own moral from Burchett’s experience. For the great domestic political significance of Burchett is that his persecution by the Australian government – like that of the leaders of the Seamens’ Union whom the Bruce government attacked in the mid 1920s, and our contemporaries, the naïve misfit David Hicks and the Indian-born doctor Mohamed Haneef – shows that our government can, and regularly does, systematically abuse its executive control over external affairs and citizens’ liberties, by expelling and excluding token quarry, to prosecute partisan political causes. Whatever views individuals have about Burchett, they need to factor this unseemly reality into their assessment.

Comments powered by CComment