- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Custom Article Title: The bohemian way

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The bohemian way

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Like the theatre backstage, the artist’s studio has the look, sound and smell of the creative moment. For romantics, this is the place where genius ignites invention, where the down-to-earth mess of paints, brushes and canvas is transformed by an inspiring atmosphere. For historians such as Alex Taylor, however, the myth masks a different kind of reality: the social manoeuvring, economic strategies and self-conscious publicity of artists in search of a living. His scholarly book is a welcome alternative to recent photographic publications that attest to the continuing glamour of artists in their studios.

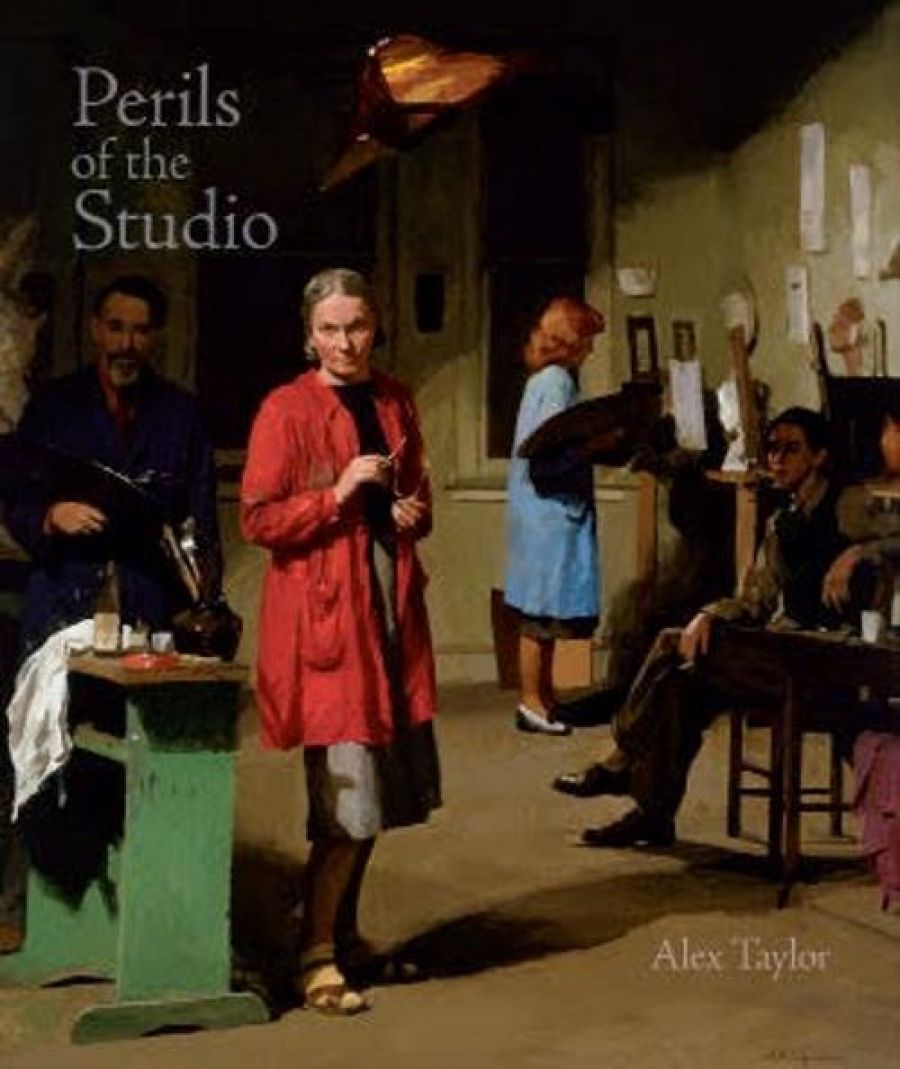

- Book 1 Title: Perils of the Studio

- Book 1 Subtitle: Inside the artistic affairs of Bohemian Melbourne

- Book 1 Biblio: ASP, $59.95 hb, 215 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Rather than the artists or even their art, this study concentrates on the cultural structures determining their lives in Melbourne in the early years of the twentieth century. Sometimes these were specifically architectural. Taylor devotes his first and most cohesive chapter to Grosvenor Chambers at 9 Collins Street, built in 1888. While modest in style and scale compared with the Melbourne Club across the road, Grosvenor Chambers was extraordinary because it was purpose-built as artists’ studios. Commodious and prestigious, it was home to an impressive array of occupants, from Tom Roberts in the 1890s to Mirka Mora in the 1950s.

Taylor describes the waxing and waning of bohemianism in Melbourne during a time when wine was considered ‘foreign and decadent’ and the Paris end of Collins Street was reported to be the ‘only place where one could “wear corduroy trousers without being taken for a poofter”’. In addition to tracing the early influence of Henri Murger’s Scènes de la Vie de Bohème (1851), George du Maurier’s Trilby (1894) and Oscar Wilde’s Picture of Dorian Gray (1890), he demonstrates the importance of bookshops, not only to source visual illustrations but also as meeting places alongside clubs such as the Lyceum and the Savage. Likewise, he shows how the studio acted as a place of social exchange and promotion with parallels to private drawing rooms. Indeed, Tom Roberts’s studio was the perfect model of a modern aesthetic interior, all Japanese fans, trays, textiles, wicker chairs and wattle branches. His exquisite portrait of Mrs Louis Abraham among these artefacts demonstrates the influence of this elegant environment over his art.

Taylor brings out the difficulties faced by women in establishing studios. Of course they could not win. Either the studio threatened their very femininity, causing a neglect of domestic duties as expressed in a range of sexist cartoons, or, more insidiously, the studio was seen as a continuation of home and making art was merely a hobby. Yet Taylor is less convincing when he claims that women reacted by imitating men in their self-portraits. To perceive a ‘masculine air’ in Nora Heysen’s imperious gaze and Dora Chapman’s candid confrontation is to perpetuate, not dispel, prejudice about women’s professional persona.

This study includes new documentation for a multitude of aspects of studio life, from controversies about female models and the curiosity of visitors, to the commercial employment of painters by advertising and display industries. Taylor also effectively establishes the dominance of the city studio in artistic practice, despite the purported Australian preference for working outdoors. Although works of art receive scant attention, there can be no doubt about the value of the diverse material assembled here. A stronger voice, however, might have given it more persuasive shape and argumentative weight. The title of the book, Perils of the Studio, hits a curious, deliberately quaint, note. Though it may have an historical rationale, it surely undermines the seriousness and relevance of the subject.

I also have mixed feelings about the design ‘featurism’ that divides the chapters with oversized photographs of artists’ palettes, skidding across the white expanse of the page like orbiting spacecraft. While they are stunning photographs, the material should speak for itself. There is a current tendency in Australian art and historical publishing to add features and colour-coding that border on gimmickry. Fortunately, the design of this book with its generous margins is otherwise crisp and clear, encompassing a complex array of photographs, documents, prints, paintings and cartoons with scholarly and informative labels. A major oversight, however, designates the Notes as Bibliography and vice versa, unfortunate when both contributions will be valuable to future scholars.

The relevance of this study is testified in the tragic demolition of the Grosvenor Chambers studios in the 1980s and in the continuing battle by artists to maintain an inner-city presence, as apparent in the labyrinth of studios in the Nicholas Building in Swanston Street. While the bohemian way of life is a myth invented and promoted by artists, it still holds power as a model for the conditions required for creativity. Although this book does not attempt to penetrate this mystery, it is instructive in documenting the social consequences of the choice of such a precarious profession.

Comments powered by CComment