- Free Article: No

- Custom Article Title: Quite an experience

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Quite an experience

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The tasteful title of this autobiography echoes the story once told of how the ebullient Italian producer Filippo Del Guidice performed the same disservice to J. Arthur Rank and survived to become a force in the British film industry. David Stratton, after looking sideways in a Venetian toilet, never looked back – despite Fellini’s understandable choler.

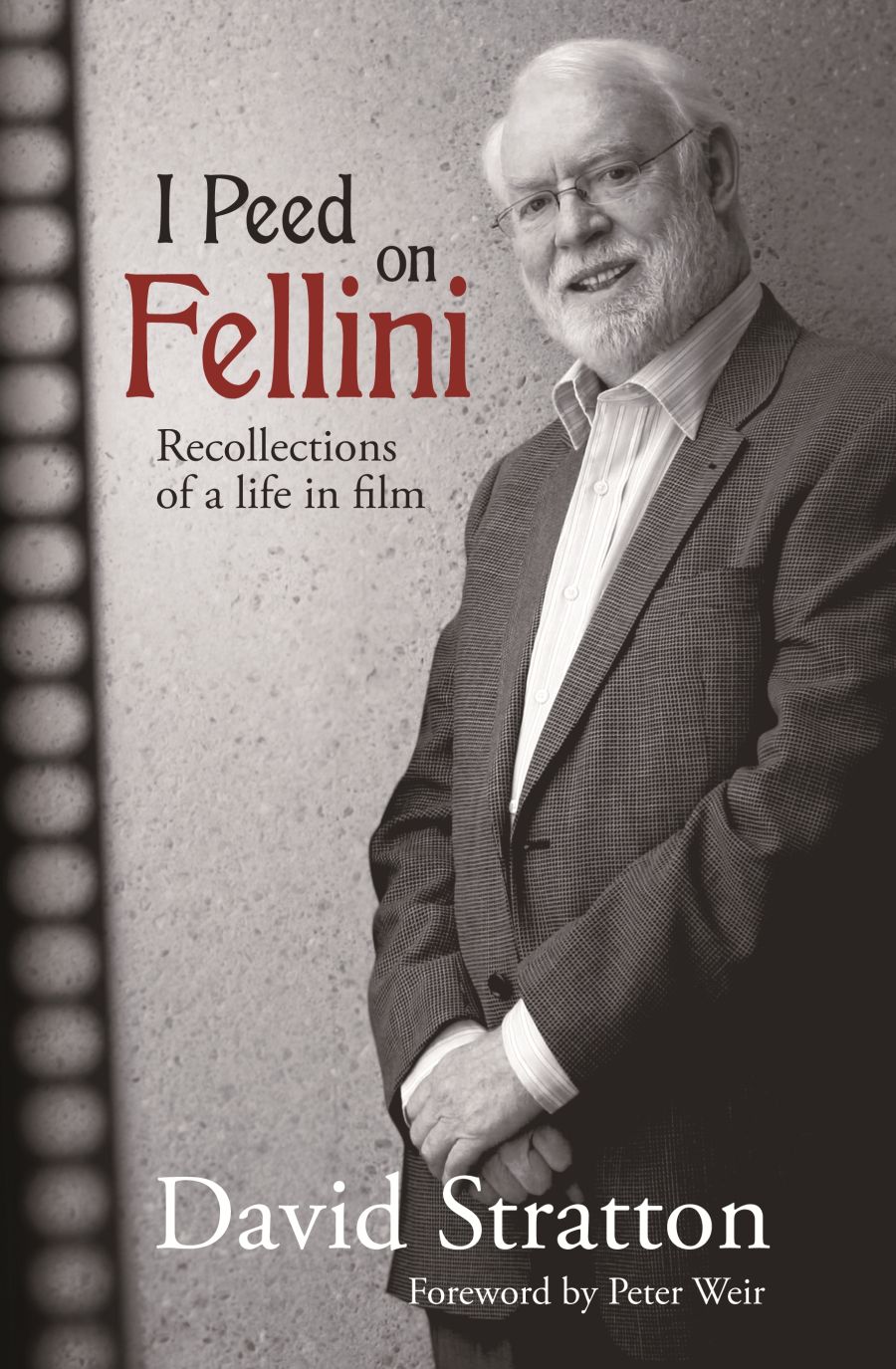

- Book 1 Title: I Peed on Fellini:

- Book 1 Subtitle: Recollections of a life in film

- Book 1 Biblio: Heinemann, $34.95 pb, 368 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Forty-odd years later, Stratton is best known as co-presenter with Margaret Pomeranz of SBS’s The Movie Show, which transferred to the ABC as At the Movies. Pomeranz doesn’t enter the book until page 290, and there had been a range of film-related activities before Stratton started to be recognised in the street as a result of his television exposure. It may appear surprising to some that they have lasted so long – this middle-aged pair: a seemingly zany woman with big earrings and a somewhat uptight man in suit and tie – but the fact is that they have survived, not only different channels but changing public tastes in movies.

Pomeranz, a producer/writer at SBS well before she and Stratton teamed up, claimed that she wanted to bring out ‘the other side’ in Stratton, ‘the funny side, the raconteur’. I think it must be said that she failed, but that doesn’t seem to have alienated the viewers, who stuck with Stratton and Pomeranz when they left SBS in 2004, after a bitter conflict with new management, and found a comparable niche with the ABC. It is useful to have this contretemps explained, and it doesn’t redound to the credit of SBS.

Stratton is one of those autobiographers who feels the need to start with the grandparents on either side of his family, to work his way through the family fortunes (the grocery trade in his father’s case, and for a time Stratton himself looked headed for this), to chronicle the vicissitudes of education and so on, before getting down to what made one interested enough in him to want to read about him in the first place. Stratton’s obsession with film is what marked him for life. Only his maternal grandmother, who took him at an early age to Duel in the Sun (1946), shared this interest. We should all have had such grandmothers.

Arriving in Australia with his first wife, Margaret, in the early 1960s, Stratton adapted to his new country and simply stayed. There is rather a lot about travels with friends, about looking for jobs and flats, about finding fellow film ‘buffs’. (I am always surprised to find that people who take films – or opera or whatever – seriously use this word, which trivialises their preoccupation.) Stratton joined the Sydney Film Festival as a member of its selection sub-committee; in 1966 he was appointed its director. From this point, every-thing else, including marriage and fatherhood, took second place in a life dominated by hurtling round the world’s festivals in the interests of Sydney’s and by endless conflicts with censorship bodies.

There is no doubt that Stratton has had a full and gratifying career. When he gave up the SFF directorship, he concentrated on writing, for whatever journals or papers asked him to, including Variety and, much later, the Australian, where he still shares the reviewing with Evan Williams. In the 2000s, while maintaining his television presence, Stratton has also taught Continuing Education courses in film history at the University of Sydney. He now contrives to do this while living in the Blue Mountains with his second wife, Susie.

I am aware that this review is in danger of becoming little more than a list of his appointments, but one of the problems with the book is that it moves with unrelenting linearity through jobs and trips and meetings. It is all more or less blameless: it slides down easily like invalid food, but it has no real edge, no sharpness, no perspective. The book’s final chapter, in which Stratton talks of his commitment in relation to political and social events, comes almost as a surprise. It has a tacked-on feel to it, when the book might have benefited from the integration of such attitudes into the texture of the emerging career.

My real worry with the book is to do with its platitudinous style and with the frequent banality of its observations. On the foreign festivals he attended, Stratton offers such unrevealing commentary as having done ‘a fair bit of sight-seeing’ or having had ‘quite an experience’. He has clearly met a great many interesting people, but though they may have ‘hit it off’ (as he often says), he never gives any sense of what made these encounters so memorable for him. I feared the writing was on the wall, as it were, when he recalled that, at his twenty-first birthday, ‘close friends and family were in attendance’. I mean, whom did he expect: the Luton Girls’ Choir? There is no ear for detecting clichés: Ron Moody was so funny that he ‘kept us in stitches’; Diana Dors had changed her name ‘before hitting the big time’; an idea is condensed ‘in a nutshell’. It may sound merely captious to refer to such examples, but this sort of writing will for some readers be a barrier to engagement with thematerial. My personal linguistic Geiger, and this book reminds me of it several times, is never to trust the prose of someone who ‘purchases’ things rather than ‘buys’ them. There is sometimes almost a touching faith in our caring about how Stratton got to places, who met him, what kind of hotel he stayed at, and with whom he ‘spent time together’. I used the word ‘linearity’ before, and there is too often no more than a sense of ‘then’ or ‘next’ or ‘after’, when one would welcome shape and assessment. On the other hand, there are very few obvious errors (‘Diana’ instead of ‘Dinah’ Sheridan; Sylvia ‘Sims’ instead of ‘Syms’; ‘Stefan’ rather than ‘Stephan’ Elliott; Louise Fletcher won Best Actress, not Best Supporting Actress) of the kind one is apt to find in memoirs, and that is a relief. It means that the ‘information’ of the book can be trusted, even if one keeps wishing Stratton had more of an eye for the detail that would vivify the experience of a place or a meeting or a film. There must have been more to say about Joseph Von Sternberg or Wim Wenders or even Joan Fontaine than is on show here.

If the foregoing seems ungenerous, it is only fair to add that the author does, in however pedestrian a style (riddled as it is with acronyms), provide a clear enough account of the changes in Australian film culture over several decades. He also emerges as an amiable man, and, as one who shares his passion for film and who also rates Newsfront (1978) as his favourite Australian film, I want to acknowledge his diverse contributions to that changing culture. Fans of The Movie Show, and for all I know their name is Legion, may prefer to listen to Stratton rather than read him, but what he has recorded here is worth having set down.

Comments powered by CComment