- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Travel

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘The nearest thing on earth to a Black Australian is a White Australian, and vice versa,’ observed novelist and poet Randolph Stow some years ago. Nicolas Rothwell might have pondered the idea on his more recent wanderings as northern correspondent for the Australian. His north is not simply geographical. It fans south and west from Darwin, and east as far as Arnhem Land. Its core is in the Centre, in the Aboriginal realms of the Western Deserts: not only another country, but also, in the book’s closing phrase, ‘another time’, another dimension to the Australia we think we know. In a tribute to Darwin’s fabled Foreign Correspondents’ Association (whose members are forbidden to file the crocodile stories that southern editors want), Rothwell quotes a Latin motto, ‘Austrem Servamus’ (‘We serve the South’). It’s a droll reminder of how far the correspondent’s words must travel, through a dirty and imperfect lens, to reach from one place to the other. The mediation of numinous, heavy-laden revelations from this remote other country for mainstream consumption elsewhere is the high-wire walk of this book.

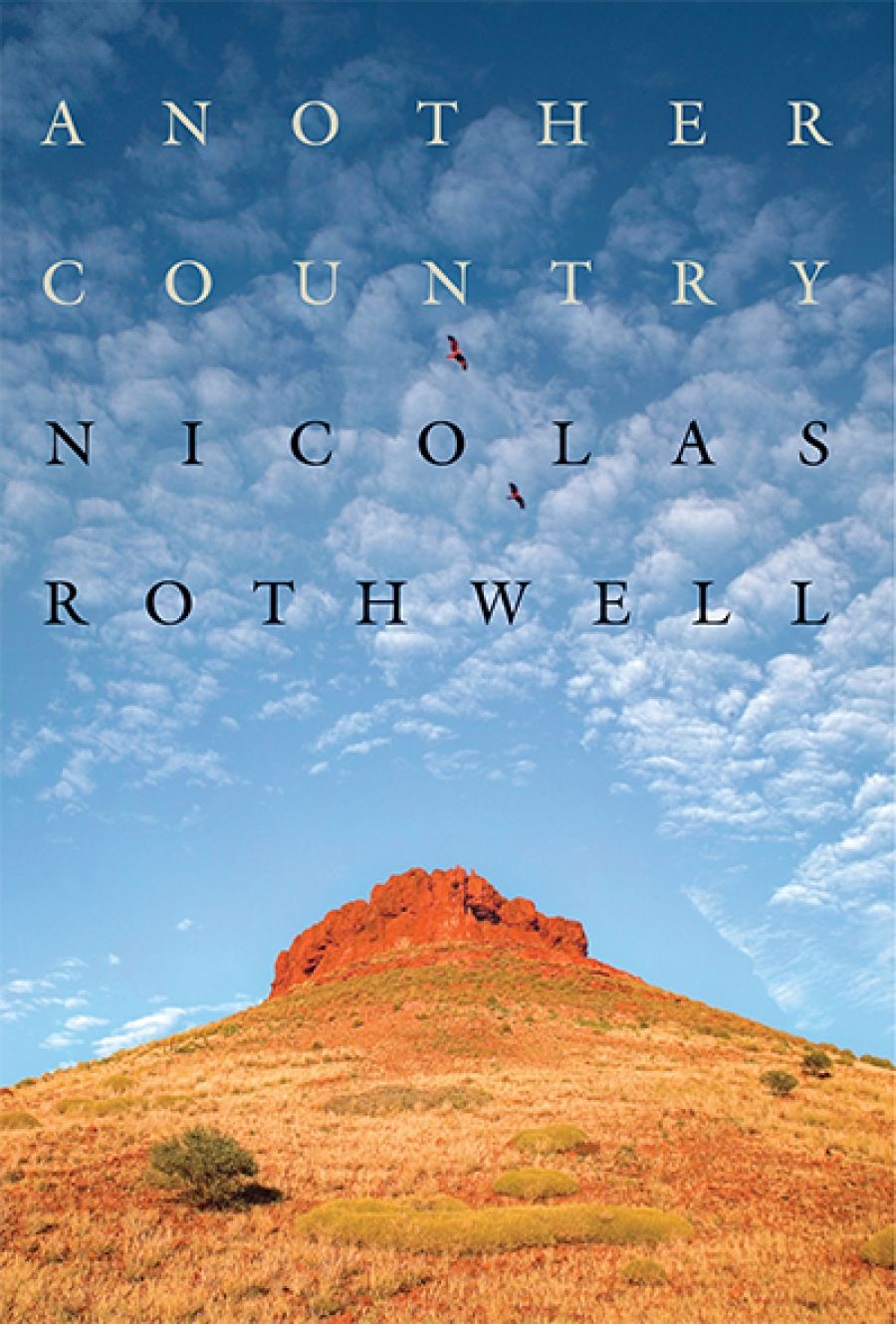

- Book 1 Title: Another Country

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $32 pb, 305 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/dbxDy

Encounters with indigenous masters point the way. The terrain is then approached through some haunting whitefella stories. There’s the ‘ex-place’ Goldsworthy, for example, a 1960s Pilbara mining town that was erased under the terms of the lease, leaving only a street-tree pattern of acacias behind and, for a few individuals, formative memories ‘full of life’s immediacy and jump, yet back-lit by the sadness of … retrospect’. Other essays diagnose the plight of remote Aboriginal communities, finding disease, poverty, generational change, disempowerment and ‘a sense of spiritual crisis’, yet also the hope of programmes that here and there are working well. The rest of the book looks close-up at Aboriginal art across the region. A gallery of affectionate and dignified portraits of individual artists leads us to art centres in out-of-the-way places where a glorious artistic flowering has come about in distressed and fragile circumstances. Celebrating the art, Rothwell chastises Australian art critics for their superficial engagement with this ‘exalted material’ and coruscates ‘the scams in the desert’ that exploit artists and corrupt the market. In a moment of pathos-filled insight he comments that ‘the images of Makinti [Napanangka] holding up the art made in her name’ for a photograph that will be used to document its authenticity ‘have an odd resemblance to images of Western hostages in Iraq pleading for their lives. It is not, one feels, the ideal existence for one of the nation’s most treasured artists.’

Rothwell argues that the creative current of Aboriginal art is ‘born of the collision between tradition and modernity, and is best appreciated in a double register drawn from those two contending realms’. Such doubleness of vision abounds in this book as the author – questioner, an ambiguous guest – participates in the ‘tidal exchange’ of ‘“two-way” learning’, moving between real and imagined worlds. On a walk through the bush with a distinguished Yolgnu artist, the pattern of rain takes him ‘for a split second … inside Gawirrin’s bark-painted world’. Images respond to images, cross-culturally, in receding reflections. Noting that the story of the film Ten Canoes (2006) descends from a photograph taken by anthropologist Donald Thomson in the 1930s, Rothwell comments that ‘this Yolgnu fascination with, and cooption of, the images others make of them is … entirely characteristic …’ The image is the expression of a world, carrying the past into the present and future. It has power to recreate and restore. This is redemptive art of exile and memory in a time of chaos, a ‘late-dawning mirror of tradition’ in which the mostly elderly artists have seized the means available to express their authority and to transmit their knowledge. As Wingellina art coordinator Amanda Dent suggests, the artists ‘could prove what they really were, and still are – giants, giants of grace and beauty in their desert landscape. Art was the only way they could show themselves to their community, and to the world.’ The comparisons are grand and telling. Rothwell likens Western Desert elders visiting an important site to ‘some family of displaced gentry from a war-torn reach of Central Europe, returning after years of exile to their ancestral home’. He mentions Siena, where early fourteenth-century artists achieved a rare synthesis of spirituality and realism, East and West, that disappeared when the Black Death wiped out three-quarters of the population. Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s frescoes of Good and Bad Government survive as elegiac reminder of an unsurpassed cultural moment. Like those great paintings, the desert masterworks combine the energy of innovation with the weight of lament. In Rothwell’s consideration, this Aboriginal renaissance might perhaps be ‘more perfect for being as brief as a supernova’s glare’.

Is this romantic or pessimistic? Is the exaltation tinged with irony? Another Country is a book of angles and tones that vary as the author changes hats. He characterises his ‘essays and memory fragments’ as ‘a low-level light aircraft journey … constantly swooping down and coming in to land’. He is witness, go-between, advocate, journalist, speculator and subject. These facets are Cubist in the way they interact and sometimes disorient us. Reported dialogues entertain views that the author might not always want to voice himself. Is he answering his own question when he responds to a child about what the adults are up to: ‘I imagine we were trying to fill up some space inside ourselves’? Outer epiphanies mirror inner flashes. I am reminded of Aby Warburg’s intense time with the Hopi Indians in 1895–96, when the art historian intuited the channel of connection between civilisation and destruction. Warburg quoted Goethe to explain the oneness that enabled him to see into what he was seeing: ‘If the eye were not of the sun, / It could not behold the sun.’ Something similar is true of the shifting affinities that allow Rothwell to read this art as he does.

Nicolas Rothwell’s first book was a novel, Heaven and Earth (1999), a grand yet inward rendering of the climactic collapse of Eastern Europe in 1989 and after. His second book, Wings of the Kite-Hawk (2003), was a virtuoso sequence of dramatised non-fictional investigations of people, including the author himself, who engage with remote Australia in transforming ways. This book is more modest, more cautious and probably wiser. The writing is subtle, elegant and disciplined, even when the direction is ‘mazy’ – a favourite word. There is a suspicion of language, the writer’s stock in trade, that coils back repeatedly, as the limits of what can be known and said are acknowledged. But the author is equally determined to point beyond division to what is of ‘transcendent value’ in the ‘intellectual architecture’ of Aboriginal society. ‘Why are we still speaking past each other, why can’t we see ourselves as one?’ an old man asks him.

The book has a personal frame. Through the shimmer and shadow presses an insistent question. Returning repeatedly to where the art comes from, the author asks ‘how, from such chaos and devastation, beauty so pure can mount’. It is an abiding human question. ‘Don’t be so sad about all that history,’ Peggy Patrick tells the mournful author at the Mistake Creek massacre site where a big mob of her people were killed. ‘There are other stories now … there’s this world too.’ What is the link between happiness and grief, ending and renewal? If another country can illuminate that mystery, as this fine book does, it’s worth attending.

Comments powered by CComment