- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In September 1943, seventeen commandos of Z Special Force, led by Lieutenant Commander Ivan Lyon, attacked and sank with limpet mines seven ships in the Singapore harbour. A year later, in October 1944, when the Pacific War had only months to run, a repeat performance failed and all those involved were ...

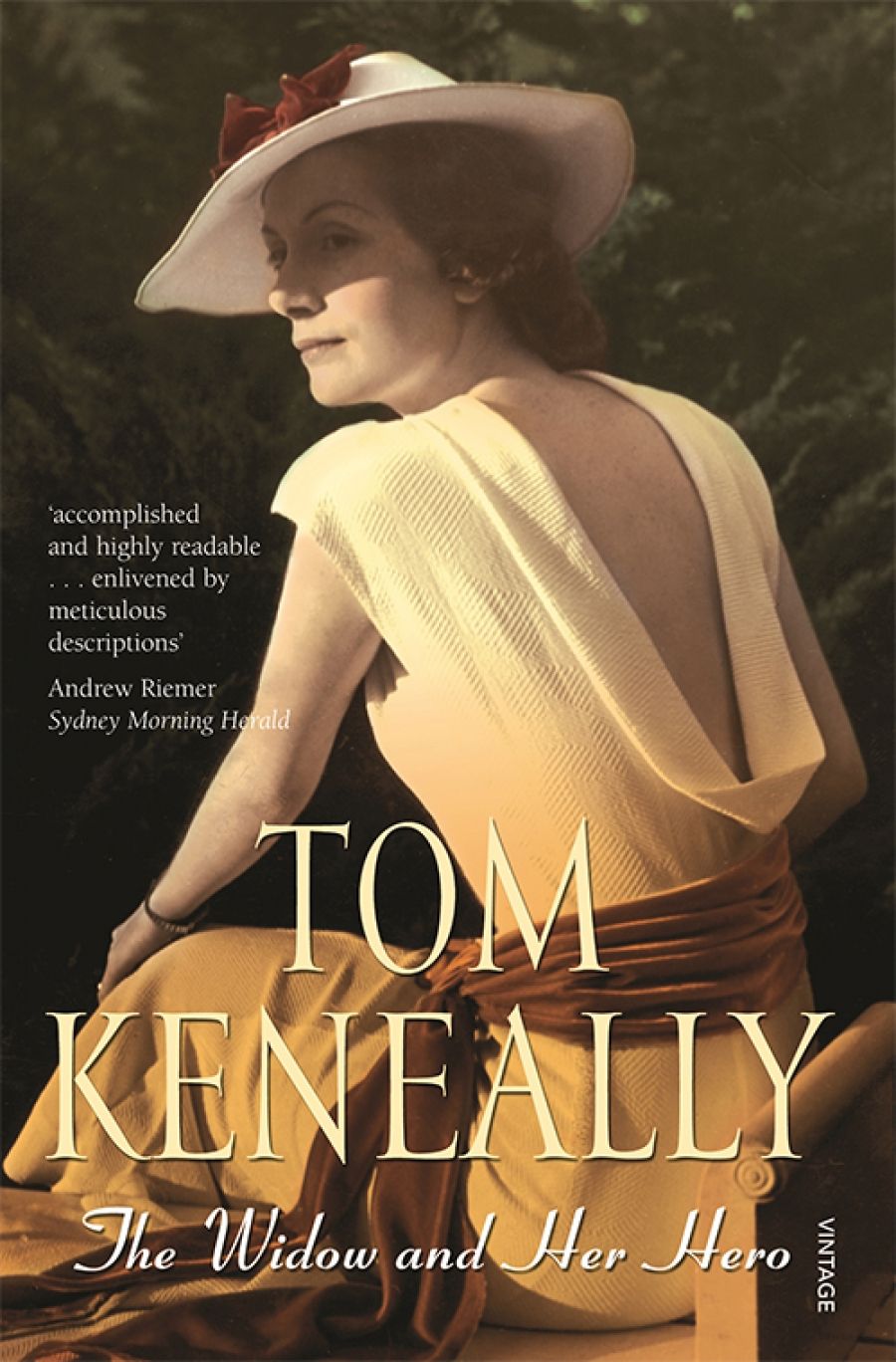

- Book 1 Title: The Widow and Her Hero

- Book 1 Biblio: Doubleday, $49.95 hb, 297 pp, 1864711011

The novel opens jerkily, as if it is a reverie that has been interrupted, with names that need connecting: Leo, Hidaka, Reformatory Road. Captain Leo Waterhouse is one of the title characters. The narrator is the other. She is Grace Waterhouse, now an octogenarian who, while she reflected that ‘I knew in general terms that I was marrying a hero’, has become increasingly pensive, if not altogether sceptical, about what heroism means and does to men. Hidaka, also still alive, was a translator at the show trial of the survivors of the operation called Memarang. Reformatory Road was the site of their execution, one of the many such scenes that Keneally’s fiction has to show, from Halloran’s in Bring Larks and Heroes (1967), to Jimmie’s in The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith (1972), to Joan of Arc’s in Blood Red, Sister Rose (1974). Keneally’s imagination has been drawn to these episodes of formal brutality and to the lives that so abruptly end.

If he disclaims this book as a fictionalised version of the Singapore raids, Keneally has been as scrupulous as always in his historical novels. His sources are numerous, his research painstaking. However, the question of sources is vital in a different, although related way in The Widow and Her Hero. Grace’s narrative draws on many sources that are disclosed to us gradually and in the order, with long delays, that they come to her attention. Journals of his time in training come to her from Leo. She is also informed by the investigations of Mark Lydon, to whose book The Sea Otters (1968) Keneally gives the publisher Cassell, his own in this period, at the beginning of his career. (Keneally has in mind his own primary source, Ronald McKie’s The Heroes, 1960).

From her own part in these events, and from varied testaments, Grace shapes a story that she had originally intended for her granddaughter and great-granddaughters, but she finds that ‘it grows to have a vaguer, more general audience’. Latest in Keneally’s long line of characters who are authors (compare the high quotient in another serious ‘action’ novelist, Ernest Hemingway), Grace is one of his pithiest: ‘yearning suited the times’, she tells us, ‘widowhood was my education’. Compared with the derring-do of heroes, Grace reckons that ‘it’s longing and misery that are three-dimensional’. In this she has company: Dotty Mortmain, whose husband will go on both expeditions with Leo, and two other widows with whom she will reluctantly trek to cheerless Canberra after the war, to discover why there were no medals for their lost heroes. Now Keneally makes a return of his own, to the setting of another of his novels of World War II, The Cut-Rate Kingdom (1980).

The depiction of Grace in her role as narrator is one of Keneally’s subtlest portrayals, an exercise in craft that compels admiration. For if the life of the hero in action is unproblematic, even if it might be fatal – ‘each detonation enlarged their legend’ – the life of the woman left behind with a cherished store of memories is not. As one new revelation gradually follows another (for instance the ‘suicide letter’ from one who feels that he might have been ‘the last war criminal’), Grace is visited by ‘the old fear that something new might emerge which must be borne, something dangerous to the honour of Leo’s ghost and something perilous to me’. That is, Grace does not want to know what Keneally the novelist has to make her tell us. The last of these revelations will make her feel as if her soul was ‘breaking out in hives’. The men who participated in these adventures are drawn – by contrast with Grace – with a risky but deliberate two-dimensionality by Keneally. It is as though desperate action will confine as much as it expresses character. Leo is patently decent, loyal, handsome, even though he bears a close resemblance to none other than Errol Flynn (‘He’s a Tasmanian, you know’). Leo’s sorrow is for his father, captured by the Japanese in the Solomons; killed when his prison ship was torpedoed by an American submarine. Keneally’s use of this detail suddenly illuminates a whole canvas of war. More allied prisoners died in this fashion than on the Burma railway. The Boss of the raiders is Charlie Doucette, who fancies him- self as ‘a pirate chieftain’, but who is, to Dotty Mortmain, ‘that Irish chancer’, ‘a madman born out of his time’. The minor parts are filled in with respectful care, but not at length. It is, after all, with the consequences of the raids that Grace’s story is concerned.

Yet it must also involve itself with the days and workings of the war. Keneally presents an intriguing account of inter-service and international rivalry. Doucette is especially resentful of the American colonel Jesse Creed, whom he believes is trying to stall the mission. The theory advanced is that the dead hand behind this is General MacArthur’s, his motive resistance to the re-establishment of British imperium in the Asian territories taken from it by the Japanese. Creed will at last come back to Australia with another story of how the lives of individuals are sacrificed to larger designs, thus enraging Grace, but by now hardly surprising her: ‘Someone as precious and complex as Leo written off by people in temperate, secure Melbourne.’

Heading into action, far from the southern capital, Doucette carries with him a copy of Chapman’s translation of Homer’s Odyssey (Keats valued this so much that it gener- ated his first significant poem). The book, the choice, is emblematic of the dash for adventure, the flight from domestic life. In fact, Doucette had believed his wife and step- son dead. When they are declared alive, his telling reaction is to feel that he has not been sufficiently moved. Odysseus left home for a final adventure. Doucette will not have been surprised by how his own days end.

The feckless, heroic traveller’s story of Odysseus is in Grace’s mind on the last page of this novel. She mocks such slogans as King and Country, Banzai and the rest, as ‘mere trellises upon which men uncertain of their weakness grow their peculiar and imperfect intentions’. The words stumble a little, as if from an old anger. A fresh flood of feeling produced one of the novel’s sharpest images, when Grace uses a shocking verb to describe a Canberra minister’s office: ‘heartened with pictures of fighter planes and bombers.’ Arriving at her own final words, Grace declares that she had not wanted a hero, to whom a woman can never truly be married, for ‘the heroic pose is not destined for ultimate domesticity’. Nor does the hero, one might add, ever truly come home. But Leo Waterhouse’s last thoughts end The Widow and Her Hero. They recall those that Keneally gave to Corporal Halloran in Bring Larks and Heroes, a work four decades ago in time but so near to this one in the shocking and solemn beauty of its conclusion.

Comments powered by CComment