- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: St Jerome in London

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

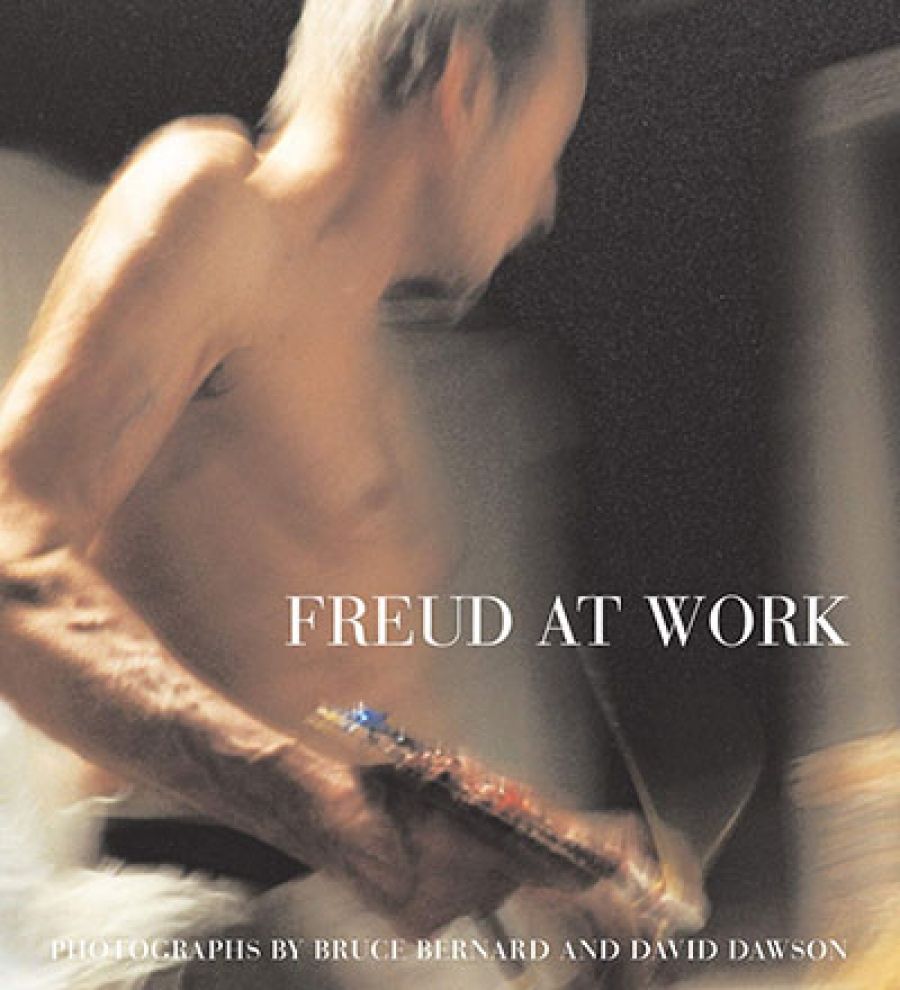

In a scholarly study just published by MIT Press (Art as Existence, 2006), Gabriele Guercio considers whether the artist’s monograph is still a viable form, given various recent challenges to artistic and art-historical theory and practice. He concludes that although the monographic model does have a future, it must be reshaped inventively. Freud at Work – devoted to the English painter Lucian Freud – represents one possible approach, combining an illuminating interview with an extensive series of studio photographs taken between 1983 and 2006. The resulting volume may seem rather slight, but when consulted in conjunction with the major books on Freud, especially the 2002 Tate exhibition catalogue, it offers many insights and pleasures. I enjoyed particularly David Dawson’s 2005 photos of the artist in action, stripped to the waist, looking for all the world like Caravaggio’s St Jerome – a suitable alter ego.

- Book 1 Title: Freud at Work

- Book 1 Subtitle: Photographs by Bruce Bernard and David Dawson

- Book 1 Biblio: Jonathan Cape, $89.95 hb, 254 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/vnqKZy

Before photography, artists – even those not known for figurative work – typically produced their own portraits, thus controlling to a large extent the images of themselves received by contemporaries and posterity. The ‘self-fashioning’ involved in self-portraiture is a topic of considerable interest, whether artists depict themselves at work in the studio; emphasise their status, like Rubens or Velázquez; or investigate their inner selves (Schiele, Kahlo et al.). Rembrandt, in his extensive series of etched and painted self-portraits, explored these and other variants, prompting one scholar to see in them a catalogue of different ‘roles and guises’ (H. Perry Chapman, Rembrandt’s Self-portraits, 1990).

Lucian Freud, born in 1922, has painted several memorable self-images, including a looming, full-length naked version, brush and palette in hand (1993), and the playful recent picture, The painter surprised by a naked admirer (2005). In these works, as in much of his oeuvre, the English painter contributes creatively to the rich tradition of representational painting to which he is a proud, if sometimes quarrelsome, heir. But Freud is also one of the many modern and contemporary artists whose image has been constructed to an increasing degree by the camera. Freud at Work features a number of memorable shots taken by noted photographer Bruce Bernard, and by Freud’s studio assistant David Dawson. Bernard matches the edginess of Freud’s work with suitably spiky photos. Dawson treats Freud somewhat more reverentially, but also eloquently describes the painterly nature of his later style; to reinforce the point, a detail of the artist’s paint-laden studio wall is reproduced as the endpapers. Bernard’s famous shots of Freud painting Australian-born performance artist Leigh Bowery in the early 1990s appear alongside images of other models; as the dust-jacket says, ‘some naked, some famous’ (in fact, sometimes both). There are also rather a lot of dogs and horses, reflecting the appearance of a number of upper-class English sitters.

Australian audiences will find various points of contact and resonance, besides the images of Bowery. In-progress photographs appear of several works, among them After Cézanne (National Gallery of Australia, 2000), including the last Freud photographs taken by Bernard, who died while the Canberra painting was in progress. Local readers might contrast Freud’s crusty 2001 image of the queen (reproduced along with we-are-slightly-amused photographs of her sitting for the artist) with the recent daub of Herself by ‘our’ Rolf Harris. More to the point, fans of Sebastian Smee’s reviews will enjoy his illuminating interview with Freud, who discovered Smee through a Sydney Morning Herald review of a show of his etchings.

The interview, while relatively short, ranges widely. One senses throughout Freud’s clear vision and self-awareness, and, even in this section of the book, a process of ‘self-fashioning’ at play. Some remarks are predictable, others less so: we learn of Freud’s earlier tastes for late-night dancing and gambling dens. The interview also includes a quirky childhood memory of his famous grandfather Sigmund (emphasising the psychoanalyst’s sense of humour), charming observations on Leigh Bowery, and lucid comments on other art and artists, notably Francis Bacon (1909–92), whom Freud knew well during Bacon’s prime, though they grew apart later. Freud remembers Bacon as a difficult but remarkable man: ‘It was his attitude that I admired. The way he was completely ruthless about his work … I think that Francis’s way of painting freely helped me feel more daring.’ Interested readers might compare the fascinating interviews that David Sylvester undertook with Francis Bacon in the 1960s and 1970s, and several studies of his chaotic London working space (now translated to Dublin): for example, 7 Reece Mews:Francis Bacon’s Studio (2001).

Comments powered by CComment