- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Subheading: Anthony Gardner reviews Johanna Fahey, Alexie Glass, Justin Paton, and Ingrid Periz

- Custom Article Title: Hermetic parameters

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Hermetic parameters

- Article Subtitle: Anthony Gardner reviews Johanna Fahey, Alexie Glass, Justin Paton, and Ingrid Periz

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

There is no doubt that the state of writing about contemporary Australian art would be in dire straits without the support of Craftsman House. In the past two decades, this small Sydney-based publisher has plugged significant gaps in the field with some of its most influential texts: Vivien Johnson’s ground-breaking work on Australia’s Western Desert painters (1994); Charles Green’s thorough mapping of Australian art since 1970 (Peripheral Vision, 1995); and one of the first, and still most concise, English-language surveys of Soviet and early post-Soviet art, immediately spring to mind. This is not to say that all of these initiatives were limited to the thrall of academia. In collaboration with the magazine Art and Australia, Craftsman House produced a series of monographs on emerging and mid-career Australian artists at a time when their CVs generally hinged on catalogue essays or the occasional review. The effect was complementary: alongside the advocacy of artists such as Janet Laurence, H.J. Wedge and Hossein Valamanesh came the franking of a new wave of important local critics: not just Green and Johnson, but Chris McAuliffe, Paul Carter, Benjamin Genocchio and Ashley Crawford as well.

In retrospect, these publications – all from the mid-1990s – marked a seemingly golden age in contemporary art, its critical support and their mutual rekindling in the name of public interest. Australian publishing seemed adamant in bucking the 1990s anti-theory malaise, that oft-diagnosed backlash against the previous decade’s postmodern binge. But if ten years feels long in politics, it can also span generations for, and of, emerging artists and arts writers – generations that have witnessed the reduction, in relative terms, of resources, opportunities and ambitions for strong critical writing. Crucial Australian-based art magazines such as Art and Text and Art Asia Pacific either went offshore or folded, or both; various publishing houses, including Craftsman House, became (at their most fortunate) local arms of multinational leviathans such as Thames & Hudson. The recognition and funding of critics’ training through residencies or cross-cultural exchange dissipated in roughly equal measure to the resurgent interest in arts administration and curatorial education. And, at least if the ‘involuntary euthanasia’ argument is to be believed, rigorous critique of contemporary art strategies gave way to the unabashed advocacy and advertising of artists through institutional bureaucracy. Consequently, the notion that a curator or other arts writer will critique or even challenge an artist’s approaches in a catalogue essay for them appears unfeasible today. This is not, of course, to deny the vital importance of training all professionals within the business of ‘contemporary art’; it is simply that the balance of opportunity – and thus the time, the period, of contemporary art – has been somewhat out of joint.

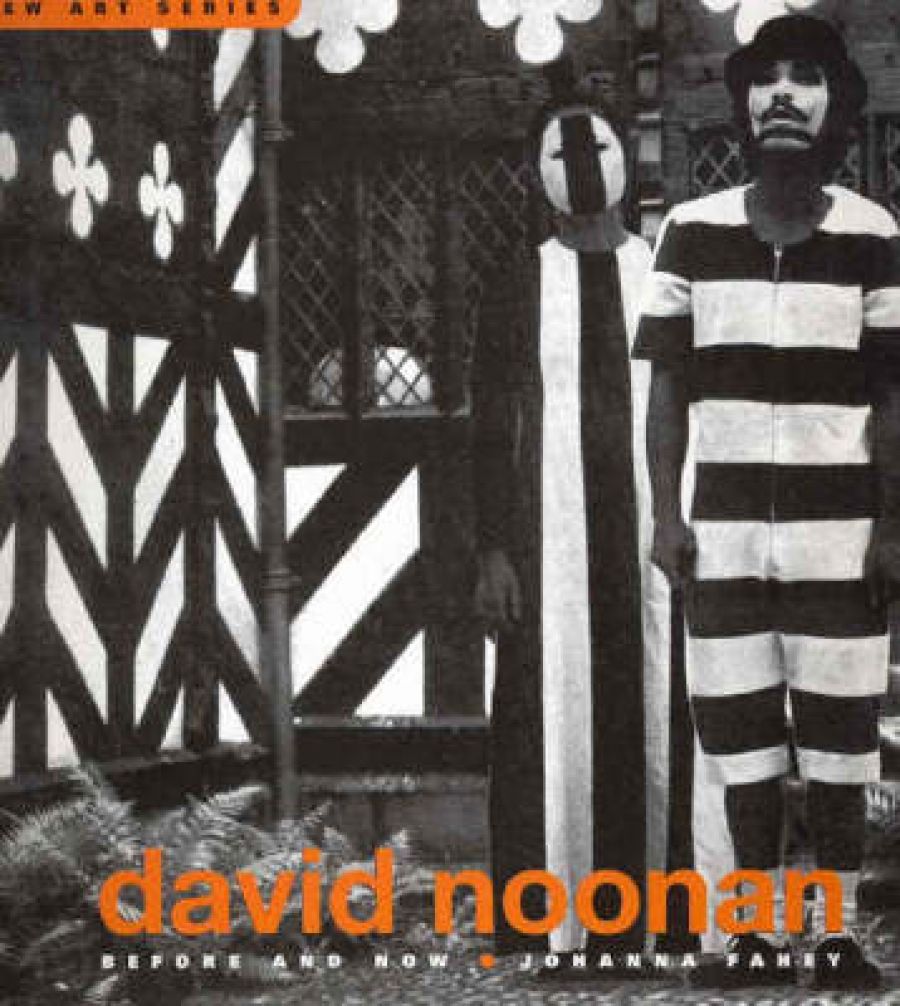

Taken together, these phenomena provide confirmation of the significance, indeed the radicalism, of Craftsman House’s latest venture. The New Art Series currently comprises four monographs and two broader surveys (New Media Art, 2003, and Craft Unbound, 2005, by Darren Tofts and Kevin Murray, respectively), and is spearheaded by general editor and one of the aforementioned critical impresarios, Ashley Crawford. Its goal is to draw the present crop of practitioners (both artistic and critical) to ‘mainstream’ attention. In most cases, this will be for the first time: Lisa Roet, David Noonan and Adam Cullen (despite his Archibald Prize victory in 2000) are not yet household names. The exception may be Justin Paton’s monograph on Ricky Swallow, which provides a timely intervention given Swallow’s status as an international art star (he was Australia’s sole representative at the 2005 Venice Biennale) and the surprising lack of anything more than a cursory analysis of Swallow’s work.

For contemporary art professionals, the series provides an invaluable archive of the artists’ output across their young careers. As Johanna Fahey remarks in relation to David Noonan, ephemeral installations and ‘behind the scenes’ events – documentation of which is usually embedded deep in artists’ or institutional collections – are now readily accessible as lavishly reproduced photographs that pepper the books. The generous documentation of works is a hallmark of the series, with each book effectively a catalogue raisonné – a rare support of artists whose careers are only ten to fifteen years old. They equally ensure a fine and beautifully produced introduction to those unfamiliar with these artists’ practices.

A series such as this can also introduce new audiences to emerging debates in art criticism and theory, and the applicability, or otherwise, of new interpretative devices to the works. It is on this level that the series is less successful, for two interconnected and problematic tropes emerge as central to Australian art practice: the romanticised isolation of the artist, and the importance of biography for interpretation. Adam Cullen’s provocative performances at art school – in which he skinned a dead cat and proceeded to wear the carcass like a pashmina, or chained his leg to a pig’s head wrapped in plastic – ensure his reputation as an enfant terrible of the Sydney art scene, isolated from the heavy theory of feminism and ethics alike. Lisa Roet’s residence in a Berlin squat, without heat in winter or proficiency in German, is the basis for her connection with the animals she saw regularly in the Berlin Zoo, and which she has obsessively represented throughout her career. Ricky Swallow carves alone in his studio with his talent accompanied solely by a song on high rotation, its gothic lyrics provided as testimony to the melancholy of his art.

Such biographically driven approaches can certainly be important for analysis, especially when argued as such by artists themselves (as Roet does throughout Alexie Glass’s thorough text). The risk, however, as with any monograph, is that historiography devolves into hagiography, especially when nearly all references cited are limited to previous criticism of an artist’s work or to the artist’s own words. Successful analysis needs to be less hermetic or at least more self-reflexive: how does ‘biography’ respond to the familiar post-structuralist refrain of the ‘death of the author’? What does an artist’s apparent self-restriction to the contingencies of his or her own life and immediate surroundings suggest about contemporary art’s expected engagement with the social (the latter having become a dominant theoretical frame in contemporary analysis)? Is the artist’s return to supposedly outmoded models to be taken at face value, treated as irony or (as the German–American critic Andreas Huyssen might argue) an interrogation of memory amid socio-political amnesia?

The effect of a hermetic analysis can be significant. It can ignore the centrality of collaboration to much contemporary practice: Swallow, we must remember, frequently works with, and is assisted by, artists with their own important practices (the most notable being Michael Conole, who is briefly acknowledged). Paton’s celebration of the handmade, the individual and the consequently auratic work – especially when set in opposition to ‘managerial’ expediency – not only falls flat but flirts with historical inaccuracy. Another effect can be the inadequate appraisal of an oeuvre, especially where complex relations to the self are involved. The Swallow text is again a pertinent example, especially given his Everything Is Nothing (2003), in which the skull encased in an Adidas hood is modelled on his own. This is not simply a memento mori in an age of logos, but a more complex critique of the imminent obsolescence of one’s own stardom: the brand name is not so much Adidas as Swallow himself, his skull a wry recognition of the contingent existence of the artist–celebrity.

Another (and related) pitfall with monographs is that the reasons for selecting particular artists need to be made explicit lest the choices appear arbitrary or merely an editor’s fancy. Such a rule of thumb for this genre of criticism is, unfortunately, insufficiently addressed in the series, in part because of its hermetic parameters. While selecting an artist of wide repute such as Swallow may be readily assumed, the cases are arguably weaker in relation to his peers. It is unclear why Noonan’s videos stand out when compared with, say, those by David Rosetzky, who won the Anne Landa Award for new media art; nor what distinguishes Cullen from another celebrated Sydney-based painter, Matthys Gerber. It is precisely the artists’ significance that suffers when their selection is not argued as warranted. Considering the fault lies with all four books, and knowing the conscientiousness with which each of these four critics has written in texts beyond these, I would question whether the series’ brief is itself to blame; whether its parameters are ultimately too narrow for the analysis that these artists deserve.

Alternatively, the New Art Series’ eschewal of depth so as to document the breadth of an artist’s output may well be a necessary compromise, as a first step, in redressing the often anaemic state of contemporary art criticism. Within these conditions, it is the very existence of this initiative that deserves recognition as undeniably important. For, at the very least, it showcases four artists of great talent, matched by four writers whose potential suggests another wave of important local critics.

Comments powered by CComment