- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Eldorado

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

This exhibition book from the National Gallery of Victoria is enthralling. It presents the imagery of British emigration, hitherto unstudied; fifteen million people fled during Queen Victoria’s reign (1837–1901). There is a mix of art history with social history: major and minor paintings and popular-culture prints; memorabilia and relics. A wedding ring salvaged from the dreadful 1857 wreck of the emigrant ship Dunbar reminds us that there was only one survivor when, at the end of the voyage, she crashed into Sydney Heads.

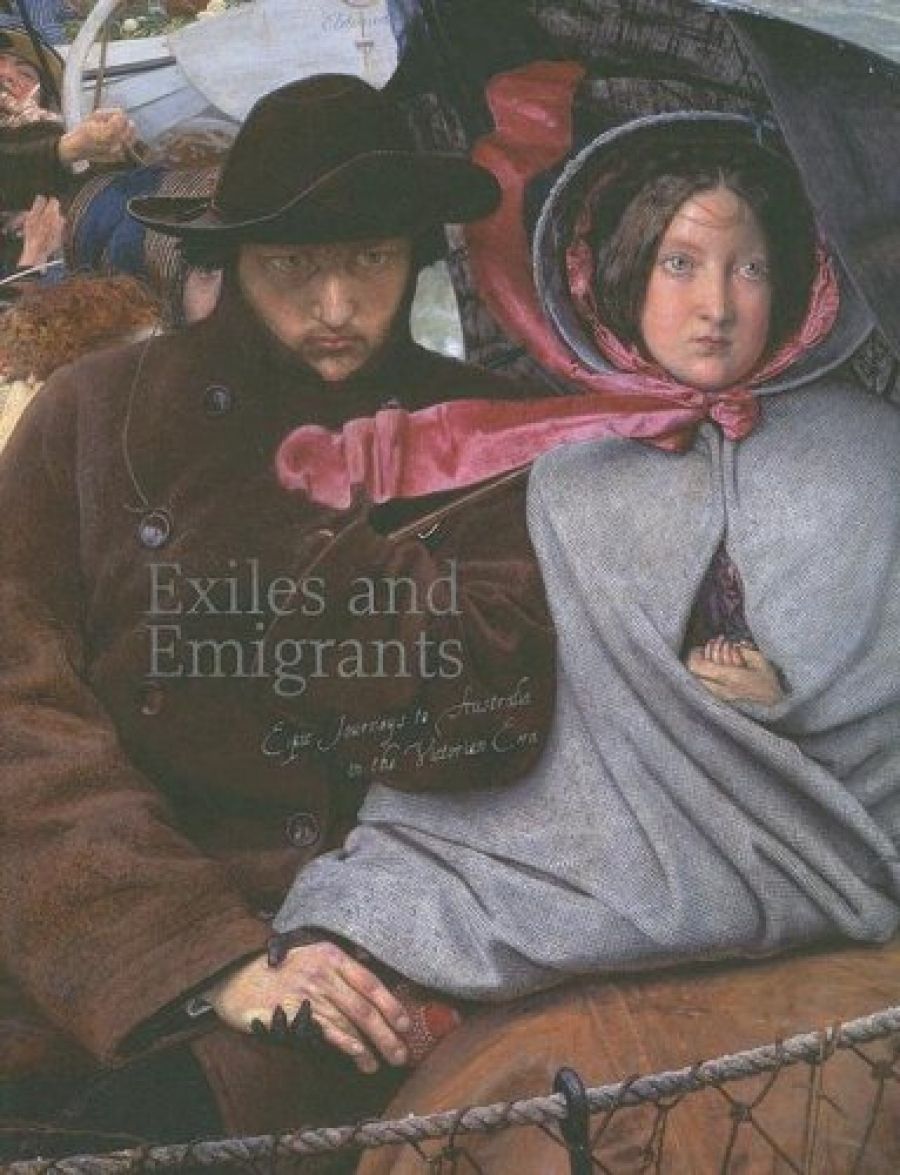

- Book 1 Title: Exiles and Emigrants

- Book 1 Subtitle: Epic journeys to Australia in the Victorian era

- Book 1 Biblio: National Gallery of Victoria, $39.95 pb, 144 pp, $49.95 hb, 0724102620

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

In Melbourne in the 1940s Australia’s first professor of art history, Joseph Burke, happily proclaimed: ‘We like them all, the bad paintings as well as the good ones.’ Provided some good art is present, it is all right to present a mixed-motives art and social-history exhibition in an art museum.

Even if a majority of these English and Australian works are minor art, many are delightful, and one is a masterpiece by any measure – Ford Madox Brown’s The last of England (1855). Its pencil study (1852) was inspired by the departure of Brown’s sculptor friend Thomas Woolner from London for Melbourne and the goldfields of Victoria; in the study, a background lifeboat is named ‘Australia’. Here in the final painting, where the principal figures are self-images of Mr and Mrs Brown, who were then considering emigration to India, the lifeboat bears a different name, of true-and-false promise, ‘Eldorado’.

Brown’s aesthetics are complex and terrific. Wide-eyed facing us, but thinking backwards to the white cliffs behind them, the thoughtful middle-class couple separate themselves from a raucous lot who celebrate the last of their downtrodden times. They all surge towards a cold empty space via the Browns’ protective umbrella and the rhyming-form protective ship’s rail. The compacted, rolling crowdedness squeezes lopsidedly into a circular format, as if trapped in a barrel, or viewed through a nautical spyglass, or a kaleidoscope. The format echoes Raphael’s Holy Family tondi and triggers recognition that this, too, is a family: a gap in Emma Brown’s shawl reveals her hand holding a baby’s. Next we absorb their secure mutuality: her shawl and his greatcoat are comfortingly warm; his hat is anchored by a string to a coat-button; from inside the greatcoat, one hand grips their shared umbrella; his other hand is visible close above the wind-refrigerated cabbages, resting bare in Emma’s other gloved hand, and it is bare so that it can be conspicuous. Brown’s orchestration of the various touching hands creates a chastely erotic sense of love; the red scarf streaming from Emma’s throat heats the connection. Strong, coherent forms symphonically reinforce the significant content, and, unlike the salvaged golden ring, this painting needs no explanatory support; we get an immediate and lasting frisson. Social history has risen to the state of great art.

Australian paintings include Tom Roberts’s Coming South (1886), a tranquil crowd of non-emigrant passengers on the gently tilting deck of a grand new passenger liner, and David Davies’ bush interior, From a distant land (1889), a good example of the stereotypical letter-from-home.

Another artistically amazing English painting is Henry Wallis’s dark The stonebreaker (1857), which turns out to be a corpse, expired at work and still there after sunset. The most over-the-top stinker is Daniel McDonald’s The discovery of the potato blight (1847), where a gloomy spirit hovers over a dismayed Irish family and a potato pit filled with rotting vegetables. It is apparently the only known painting that refers to the cause of the great Irish famine. Lent to the exhibition by University College, Dublin, The potato blight is one of many obscure but significant works found in obscure places. The tracker extraordinaire, exhibition curator Patricia Tryon Macdonald, developed the project over more than eight years, after studies undertaken at Boston University while her husband, once a proprietor of The Age in Melbourne, was teaching journalism at Harvard. A delayed project often develops into a very good project: no last-minute rush. Macdonald’s introduction and her fifty-four essays on individual pictures carry an unusually unruffled authority.

Among other essayists are English and American specialists in English Victorian painting, Tim Barringer, Christopher Wood and Susan Casteras. The Australians are Martin Terry on conditions at sea, Angus Trumble on string-pulling letters of introduction, Elizabeth Gertsakis on post office history, and Tim Bonyhady on McCubbin’s forest-lopping emigrant triptych, The Pioneer, a block-buster painting generated by colonial Federation in 1901, the year of Queen Victoria’s death, a neat closure.

Two serious publishing faults. NGV has offended the owners/lenders of works by omitting their names from the picture captions, banished to the end matter, and has similarly irritated general readers. Too many artists’ names appear in the style of a biographical dictionary or an auction catalogue. We are pleased to encounter Tom Roberts, not Thomas William Roberts, but Samuel Luke Fildes is a stranger to art history. Just call him Luke.

Comments powered by CComment