- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Silken universe

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Thea Proctor’s long career spanned the 1900s to the 1960s. Sadly, she lived to see her reputation decline. Barry Humphries, in private life a noted art collector, relates here how his characteristic appreciation of the aesthetically démodé led him to seek out Proctor’s acquaintance in the 1960s. A new generation of professional curators sniffily dismissed the grande dame, then in her eighties, as a ‘minor artist’, more important as a teacher and passionate champion of other modernists than in her own right. To Proctor, though, an aesthetic reputation was everything. ‘If I have not got that a life’s work is wasted,’ she despaired to a friend.

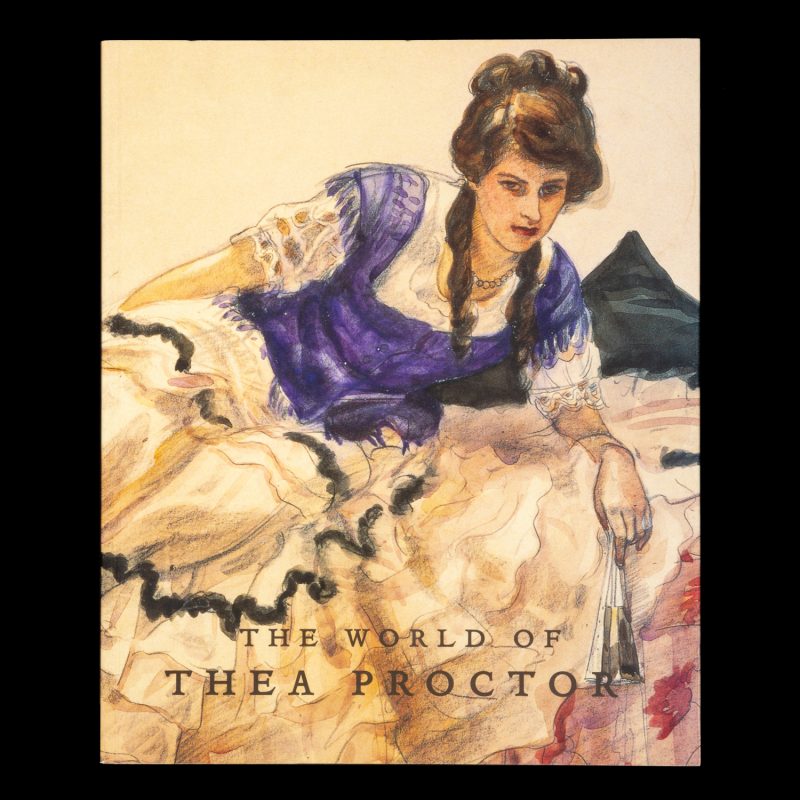

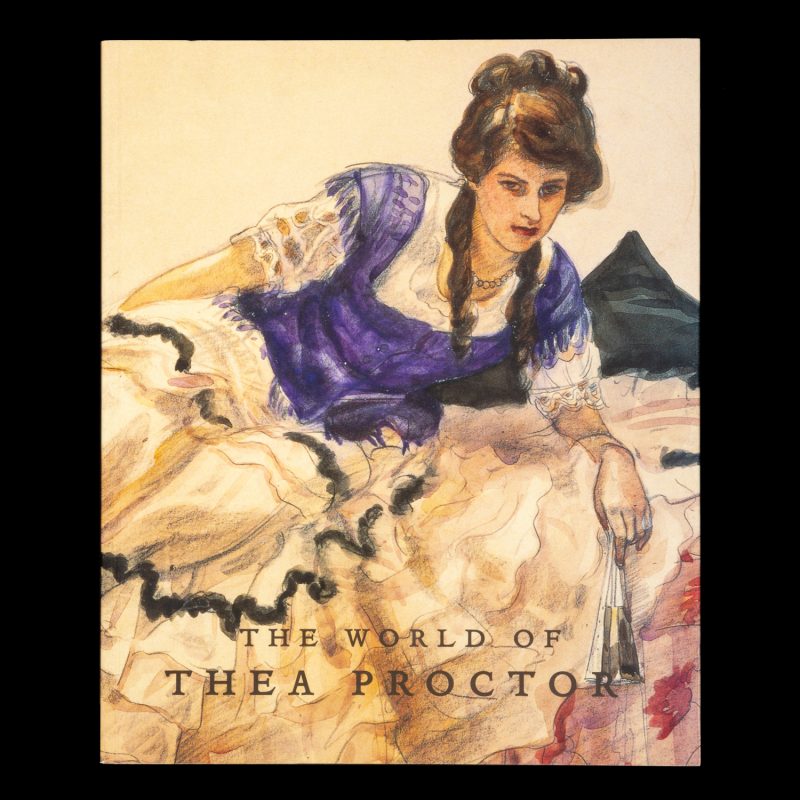

- Book 1 Title: The World of Thea Proctor

- Book 1 Biblio: National Portrait Gallery/Craftsman House, $55 pb, 185 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

The aestheticism of Charles Conder in the 1890s was her earliest influence, particularly his frothily painted silk fans, a genre she imitated and made her own. By the 1920s she had built a reputation as a leading modernist ‘decorator’ in Sydney, with the support of Art in Australia. Jan Minchin and Roger Butler’s lavish Thea Proctor: The Prints (1980) revived demand for her stunning lithographs, woodcuts and covers for the women’s magazines Vogue and The Home, somewhat at the expense of other periods of her work.

Despite all that, Proctor remained rooted in the tradition of Conder and Oscar Wilde. For her, art was always an extension of her carefully cultivated image. Returning from London in 1921 when in her forties, she set out to deprovincialise Australia by demonstrating how to be an urbane modern woman. In articles picturing her minimalist striped-and-white studio, her fancy dress and her flower arrangements, she was a model of how to decorate and how to live, importing fashion into art and vice versa. Persistent rumours of a long-running love affair with the flamboyant and much more famous artist George Lambert only added to her aura.

As well as giving us more detail than ever before on Proctor’s life, including the ‘did-she-or-didn’t-she?’ affair with Lambert, this new book, based on an exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in Canberra, shows us a different side of Proctor from the elegant Jazz-Age fashionista. Instead, we have a conservative draughtswoman who specialised in portraits of women and children. It reminds us that it was her drawing, not her graphic art and design, for which she was most admired. The critic J.S. MacDonald, no lover of ‘cactus-painting modernists’, elevated Proctor above other decorators for her ‘masculine’ skill in drawing, while to Graham McInnes, in The Road to Gundagai (1965), she was the ‘Sydney watercolourist’ whose ‘delicate, though rather anaemic art nouveau drawings were much in demand among the social set’.

And anaemic they can be, even though Proctor was a connoisseur of exotic and sophisticated colour. A favourite contrast was magenta and acid lime, an alarming combination if you don’t know what you are doing, but one that Proctor confidently carried off in a portrait photograph taken when she was eighty-five (sadly, for all the trouble she took, the picture reproduced here is in black and white). Such effects, so well exploited in her prints, drain away in her drawings and watercolours. Today, her portraits look like charming period pieces, meticulously composed, but cool and hieratic in comparison with the sexy stylisation of her best graphic work.

Nonetheless, attention to Proctor’s portraits is overdue, not least because it forces a reassessment of other aspects of her oeuvre, including her much-celebrated modernity. Even by female standards of the day, Proctor was not much interested in the kind of modernism that expressed the twentieth-century experience. Her one concession to either of the two world wars is a lithograph called Stunting (The Aeroplane), 1918, which pictures a group of women posing against the criss-crossed patterns of searchlights in the night sky. Margaret Preston’s fascination with the Machine Age, or Grace Cossington Smith’s with the surge of the city mob, escaped Proctor. Nor was she remotely interested in fashionable nationalist obsessions. One can hardly imagine a sheep wandering into a Proctor picture, and gumnuts and banksias were strictly for décor. While Preston adopted air travel and ‘went Aboriginal’ in the 1940s, Proctor’s primitivism moved no further than the Ballets Russes.

Printmaking helped make her modern by simplifying her line and flattening out her colour, but the content of Proctor’s ‘silken universe’, as one contemporary critic called it, would be at home in the eighteenth century. Children and men hover devotedly around beautiful, languorous young women, who spend their apparently limitless leisure time trying on clothes, shopping, playing in parks and gardens, and attending masked balls. Afterwards, exhausted, they collapse picturesquely on divans. It is surprising to see how many of Proctor’s images feature Victorian dress, particularly of the 1870s, the decade in which she was born. She liked Spanish and commedia dell’arte costumes and abundant Edwardian hair more than prosaic day gowns and shingled bobs. Her demure, self-absorbed heroines carry fans and parasols, not cocktails and cigarettes. The flapper’s clichéd blank, confrontational stare is almost entirely absent.

Although Proctor usually seamlessly translated her natural fin-de-siècle elegance into modern style, occasionally her famous taste let her down. Even a stunner like her cousin Hera Roberts could not save some of Proctor’s frightful get-ups. A fussy Victorian lace ensemble donned by the artist for a magazine photograph in 1929 makes her look like Miss Havisham. Proctor’s definitive portraits are those by Lambert from the early 1900s. He has her striding out with a borzoi into a swirling black landscape, turning attention from the clothes to the woman. Lambert always painted her like a goddess.

Proctor went on ‘incendiary sprees’ late in life; try as the authors might, hard evidence of an affair with the married Lambert (or indeed with anyone else) is lacking. Of course, we have his pictures, several of which weirdly juxtapose Proctor with his ultimately estranged wife, Amy, and their precociously talented children. But Proctor maintained a tender friendship with Amy until death intervened. On the other hand, she terrified Syd Ure Smith with her infuriated meddling when he left his wife for Hera Roberts in the 1920s, hinting darkly at her own blighted history as the reason for her objections. One hopes that this was not so, and that the tremendous sensuality in her drawings and in Lambert’s drawings of her was somewhere fulfilled.

Puncturing Proctor’s reserve, not to mention her mystique, Andrew Sayers and Sarah Engledow reveal that her first name was Mildred, not Alethea. She fell out violently with practically everybody in the 1920s, including Preston, but kept her taste for people, and was rewarded with the friendship of the young in old age. Although her work celebrated the indulgent lifestyle of the rich, she was usually broke, eventually reduced to taking in boarders in her tiny flat and selling off Lambert’s portraits. This absorbing book gives us a fresh, definitive account of an influential artist and personality. As a bonus, its superb illustrations considerably refine and expand our view of her art.

Comments powered by CComment