- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Sophisticated borrowings

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

There is something immensely satisfying about a work so ambitious and comprehensive as Deborah Edwards’s Margaret Preston, published by the Art Gallery of New South Wales to accompany its current retrospective on this pre-eminent Australian modernist. From the outset, we are introduced to Preston’s perennial capacity to stimulate not only debate but also downright factionalism. The introductory chapter takes the form of multiple quotes, leaving no doubt that Preston continues to ignite debate over issues surrounding an authentic Australian vision.

- Book 1 Title: Margaret Preston

- Book 1 Biblio: Art Gallery of New South Wales, $50 pb, 300 pp, 0734763743

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

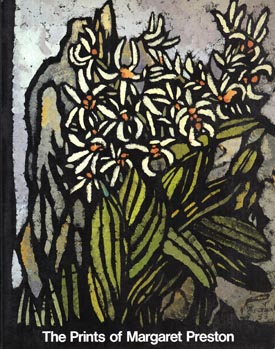

- Book 2 Title: The Prints of Margaret Preston

- Book 2 Subtitle: A catalogue raisonné

- Book 2 Biblio: National Gallery of Australia, $89 pb, 382 pp, 064225185X, $120 hb, 0642541914

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

At first glance, the voice of this outspoken and much published artist (1875–1963) appears overshadowed by the plethora of commentators distributed throughout the text (no less than sixteen writers contributed to this volume). Yet it is this mix of divergent opinions that may well provide the book with a greater longevity, illustrating as it does the partisan responses that Preston’s work still manages to engender.

Edwards presents an intellectualised account of Preston’s art and, in so doing, highlights the extent of the artist’s aesthetic and conceptual rigour. This may come as a shock to those who would see Preston as a ‘nana’ of Australian art, quietly attending to her lovely floral arrangements. Instead, Preston’s sustained rendering of native flora through the combined filters of reductive modernism, Japanese linearity and Aboriginal art is analysed with precision. One comes away with a realisation that Preston was a true pioneer whose programme for a national art remains vitally relevant to contemporary cultural debates.

For all of Preston’s high-minded ambitions, it is her engagement with Aboriginal art that remains contentious. The monograph addresses this in part through the inclusion of texts by a wide range of writers and curators, not least of whom is the Aboriginal curator Hetti Perkins, who voices a strident critique of Preston’s appropriations of Aboriginal art, stating: ‘To Aboriginal eyes it reads as a scrambled orthography of vaguely familiar words, or a discordant symphony where the notes don’t ring quite true. Preston’s passionate attempts, while well intentioned, were doomed to fail ultimately because they are meaningless to Aboriginal people – not unlike the contemporaneous government policy of assimilation.’

In contrast, Edwards emphasises that, while Preston was indeed an appropriator of Aboriginal art, she was an appropriator of a sophisticated kind. Preston’s sophisticated borrowing is especially effective in her landscapes of the 1940s, in which the colours and forms of Aboriginal art flow ever so subtly into Preston’s technical brilliance.

With similar élan, Edwards is quick to address the issue of Preston’s self-promotional tactics. For this reason, perhaps, Edwards has been less prepared, unlike others in the past, to base her analysis on the artist’s self-regarding claims. By focusing instead on Preston’s prodigious body of work and on the factual realities of her career, Edwards has succeeded in presenting a highly provocative account of the artist’s contribution to both Australian modernism and its lasting effect on notions of Australian image and identity.

Edwards’s observation that ‘Preston’s tendency to simplistic public polemics obscured her serious methodological pro-gram’ embodies much of the author’s modus operandi. Yet, while Preston published numerous articles on a range of arts-related topics, reference to her writing is tightly controlled by Edwards. This adds strength to Edwards’s thesis; however, a fuller account of Preston’s practice would have been achieved if at least some of this material had been included at length. The CD-ROM that accompanies the book would have been an ideal means of presenting Preston’s writing. Yet, despite this omission, the inclusion of the CD-ROM has enabled the Art Gallery of New South Wales to produce a thorough catalogue raisonné of paintings, ceramics and monotypes. Presented in a format that is at once accessible and comprehensive, it provides an excellent quick reference for Preston scholars.

The catalogue is well supported by a thorough overview of the developments of the artist’s career, from her early lessons as a China painter to her life as a student abroad, to her later years as a prominent figure on Australia’s artistic scene. Preston emerges from the first as a talented artist with abundant technical skill. Many of the early still lives are compelling, if somewhat derivative of European prototypes. From here, a detailed account is given of the artist’s interest in ‘the decorative’, a term that nowadays is perhaps too easily misunderstood. For Preston, the decorative was aligned with both progressive modernism and with a generalised democratisation of the arts. The formulation of the decorative as fundamental to surface and hence to modernity privileged design over subject. During her years in Paris and Munich (1904–06), Preston was exposed to a wide range of contemporary practices, and it appears that, from this period on, she progressed ever closer to a practice of pure painting.

By the late 1920s Preston was at the height of her artistic powers. In works such as Western Australian gum blossom (1928), her observational powers are acute, rendering the complex forms of gum leaves capped by the luminous presence of vivid native blossoms. Her compositional skills were likewise thoroughly refined, combining the simplicity of Japanese design principles and the reductive measures of European abstraction. In Implement blue (1927), a work that invites comparison with Olive Cotton’s Teacup ballet (1935), the artist has reduced her palette to the bare necessities. The forms are determined by strongly contrasted tones and angular intersections, while all hint of superfluous detail is emphatically absent.

Rose Peel presents an exploration of Preston’s techniques and colour theories in her chapter, ‘Drawing Connections’. This includes details of Preston’s colour charts, which the artist aligned with musical scales. Peel’s text provides an added perspective to the reading of Preston’s art, aligning it with a period interest in the correspondence of colour and music. However, Preston was not, seemingly, in the throws of synaesthesia, rather envisaging music as akin to science. Colour, by extension, could be controlled by the rationalising effects of modernity and returned anew to the service of art.

This well-researched and insightful volume represents the kind of scholarship that is much needed in Australia in the under-nourished field of modernist research. It makes a real contribution to its field and is essential reading for anyone interested in this formative period of Australian art.

In comparison, Roger Butler’s catalogue The Prints of Margaret Preston: A Catalogue Raisonné, which focuses wholly on Preston’s practice as a printmaker is a major survey that highlights the artist’s technical achievements across a range of graphic media. The catalogue, an expanded second edition of the NGA’s original 1987 publication, includes a number of additional works not found in the first edition. The catalogue illustrations lack the luminosity of the original artworks, which diminishes the viewing experience. This is compounded by the distracting layout, which shifts attention when one wishes to study the works. Nonetheless, it makes a handsome companion to the AGNSW monograph, especially since a comprehensive survey of the artist’s prints is not included in the AGNSW publication.

Butler presents an informative account of Preston’s career, while devoting a second chapter to the importance of craft throughout the artist’s practice. Butler points out that craft remained a guiding principle for Preston, a discipline that reinvigorated her practice at every turn.

Clearly, it is through examining the artist’s prints that one can survey the true breadth of the artist’s visual inventiveness. This is especially the case as printmaking was the medium through which Preston essayed a great number of stylistic codes. Series of works such as the diminutive Women’s sport (1934) are conceived in a constructivist manner, while Mask 1 & 2 (c.1928) appear as surprising precursors to Howard Arkley’s Zappo heads. Stencilling was another medium favoured by Preston, marking her strongest foray into abstraction based on Aboriginal designs. Preston’s delicately modulated monoprints challenge the popular view that her later work is somewhat diminished in quality.

Margaret Preston’s quest for a uniquely Australian idiom marks her as a pioneer. Significantly, her radical synthesis of European, Asian and Aboriginal styles predates the emergence of contemporary post-colonial discourse and should be seen in the context of both her outspoken belief in indigenous art forms and her quest for a national style. Issues addressed by Preston persist today, appearing in the work of contemporary artists such as Imants Tillers, Tim Johnson and Gordon Bennett, to name a few.

Comments powered by CComment