- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Society

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Melbourne’s fashions

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

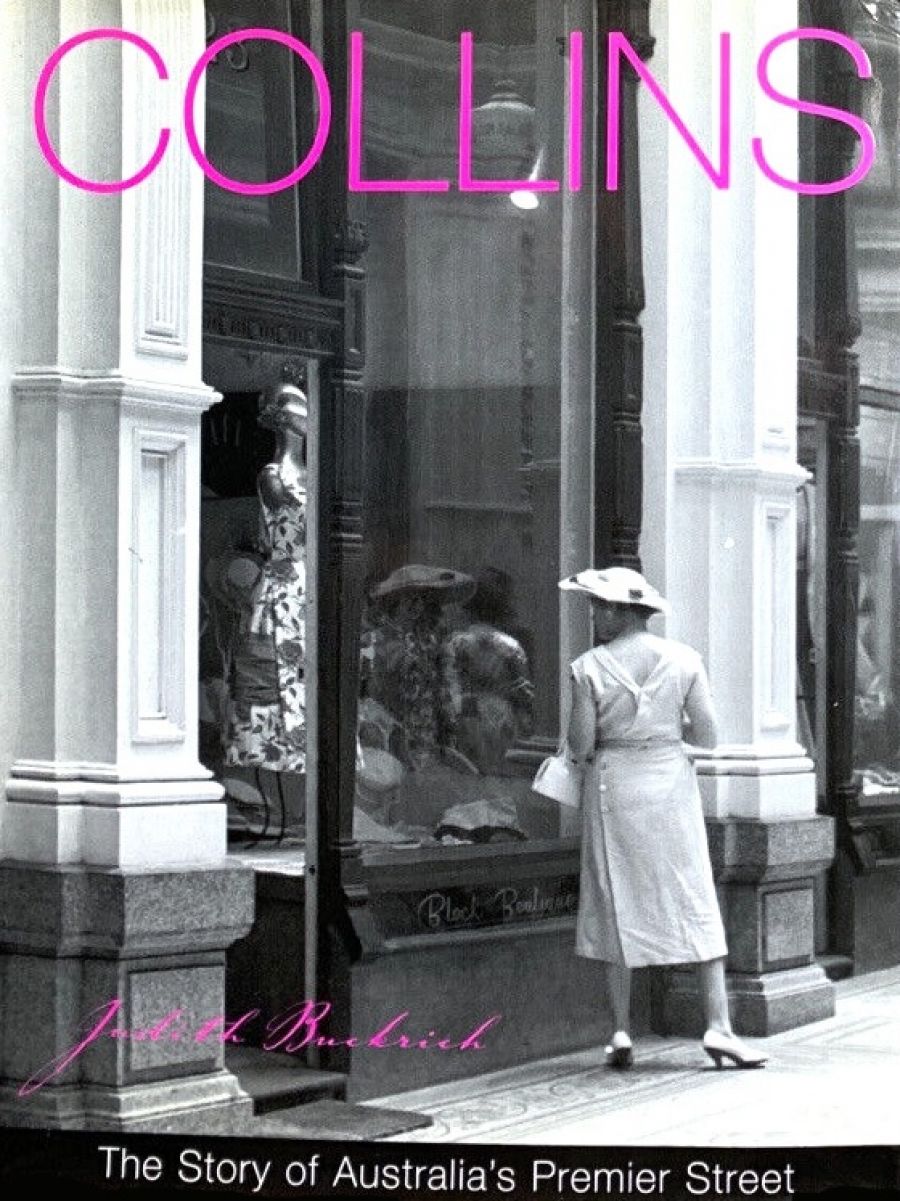

Two new books with Melbourne as their subject couldn’t be more disparate in size, form, content and accuracy. Collins: The Story of Australia’s Premier Street is a big, well-designed book. It has a mysterious provenance and more than a smattering of inaccuracies: but it has pictures. These are mostly from the State Library of Victoria, and even those dating from the early years of outside photography provide clear details of the buildings and people of the time. They will enchant even those who dare think that our premier street is not so very different from the main streets of Manchester or Madison.

- Book 1 Title: Collins

- Book 1 Subtitle: The story of Australia’s premier street

- Book 1 Biblio: Arcadia, $89.95 hb, 270 pp, 1740970578

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Title: Go! Melbourne

- Book 2 Subtitle: Melbourne in the sixties

- Book 2 Biblio: Circa Press, $34.95 pb, 306 pp, 0975780204

Collins Street is certainly the most consistently handsome street of the forty that form the central city grid. This adds up to twenty-eight blocks: the authors make it twenty-four. Two blocks of William Street are superior, but over the last sixty years the western end of Collins Street has almost come to equal its famous eastern counterpart.

The details of the book’s sponsors and willing helpers make interesting reading. One date is out by eighty-eight years. The Collins Street Precinct, a group of property owners and estate agents, funded the book’s publication, but serious financial help from the Melbourne City Council is vaguely referred to. The ‘editing and production’ help received from students of the Advanced Editing course at Monash is acknowledged. That involvement would have doubtless saved money, and it explains a lot. The book is dedicated to the late restaurateur Mietta O’Donnell. The introduction is by the manager of the Block Arcade, and the owners of that grand building contributed the preface. An afterword by Keith Dunstan adds a professional touch, combining historic comments on various buildings and personal reminiscences.

The body of the text is made up of six chapters, each on an aspect of Collins Street (its attraction over the years for painters, doctors, financiers and shoppers), but the photographs generally ignore this subdivision and appear as irrelevant but always welcome drop-ins at the most unlikely places. For instance, a hazy view of the Baptist Church introduces the section on ‘Art and Culture’. Five photographs of Scots Church, a billiards match and the Melbourne Club are used to illustrate the section entitled ‘Somewhere to Meet’. The now-gone Federal Hotel is well documented, but Collins Place (1970–75), generally assumed to have done more than any other building to destroy the streetscape, escapes censure. Even more surprising is the treatment of the Treasury Building, surely the street’s most admired structure. In a few photographs, it only appears as an arcaded blur in the far distance. It is referred to in two captions, and that was because it happened to be the place where the photographer was standing when aiming his camera at other buildings!

The book was probably never meant to be a serious architectural or social survey. It emanates a childlike enthusiasm, obviously written by someone who spent time remembered at a cinema or the dentist, followed by a double malted at The Milky Way, Hilliers or even lunch at Russell Collins or Elizabeth Collins (once the nation’s most easily located restaurants).

Collins is a treat to look at, but difficult to read, its great weight being only one reason for this. Although some early panoramic photographs show details of buildings, it is still difficult – unless one is a native – to assess just where and when changes took place. The illustrations are unrelated to the actual sequence of the buildings in the street. Captions are inadequate, oddly placed or, in some cases, non-existent. Architectural accreditation is rare and the index does not differentiate between text and photographs.

Errors abound. Collins House was certainly the home of the country’s greatest mining companies, but not of BHP. It was constructed in red granite, not bluestone. When The Hotel Australia (referred to once as The Australian) was built in 1938, it did not preserve Walter Burley Griffin’s Vienna Café. This was a persistent rumour, probably started because people didn’t expect to find a barrel-vaulted ceiling in a modern building. The new dining room was a respectful if heavy-handed reprise of Burley Griffin’s exotic 1917 space. Henry Buck’s shop was in Queen’s Walk, not Queens Arcade. The director of Georges Gallery was Robert Haines, not Hayes.

Marble-clad buildings, glamorous dining rooms and gentlemen’s outfitters are not important items in the Melbourne that is dissected in Go! Melbourne: Melbourne in the Sixties, and more’s the pity. This is a small, soft-covered book printed in China. It has few illustrations and most of the time it takes itself very seriously. There are notable exceptions. For John Rickard, the distinguished Monash historian, the decade was a series of theatrical adventures – some very brief. To illustrate one of his triumphs, he provided a photograph of himself, over-bejewelled and underdressed, as Lun Cha, a courtier in The King and I.

The authors bemoan the fact that important changes can never be neatly lumped into a decade – then they do exactly that. We were spoilt between the wars. The history of those years could be neatly boxed (give or take a year) into decades. The 1920s and the 1930s were defined sym-metrically by the Armistice (1919), the Crash (1929) and another war (1939). Had this book included the architecture and the architects of the period, they could have had a neat matching with the decade (give or take another year). Many of the great events associated with the 1960s had their roots years earlier and their effects much later.

In his 1960 budget, Harold Holt introduced a new idea: a Credit Squeeze to rein in the building boom that had begun in the mid-1950s. It did more than that. Within a year, construction ground to a halt. It did not revive until 1963. Then, early in 1971, the US tried to refinance an expensive war. The supply of money dried up and building stopped for another three years. Now that delineated the 1960s very neatly for many people.

This book is the result of a conference with the same catchy name organised by La Trobe and Monash Universities in 2002. The nineteen themes covered probably reflected the participants’ interests rather than the perceived values of the 1960s. It was certainly a decade that saw some dramatic changes: the pill and the ‘second car’ were the equivalent of female suffrage. The mechanical dishwasher, television, the end of six o’clock closing of bars and eight o’clock closing of dining rooms (not mentioned) transformed our lives.

Generally discussion at Monash was along more intellectual lines, but the arrival of the Beatles receives a chapter. That was certainly a phenomenon, but generated not by their popularity as much as the rarity of visiting celebrities. The decade saw the introduction of jet travel. While Melbourne was still not at the centre of Western civilisation, jet travel suddenly made us less inaccessible, and one could occasionally see a real celebrity walking along Collins Street. (Chapel Street’s time was another twenty years away.) Other chapters cover the aspects of life that were changed forever. An Elwood rabbi reintroduced long-forgotten practices that altered the form of Jewish weddings, the way music was played and dances were danced. Film societies then new are now a part of life and treated with respect by the exhibitors. The influence on our eating habits by immigrants (always good for a serious treatise) was then a new subject.

Both the big book and the little book chose a minor subject for their cover illustration. The Block Arcade is not the most significant building in Collins Street; nor was Jean Shrimpton the seminal figure of Melbourne in the Sixties. The continual harping on her controversial appearance (in both senses) at Flemington on Derby Day in 1965, when the length of her skirt was considered inappropriate and therefore bad fashion, tells us much about Melbourne and what interests it. Back then, nobody remarked on the appropriateness of her flat shoes for coping with the well-watered lawns. In 2002 nobody noticed that at least one detail of fashion-skirt length had remained in vogue for over half a century. For a more accurate impression of Melbourne dressing, study carefully the shopper enviously looking in the windows in the Block Arcade. It is hard to believe that Collins and Go! Melbourne have a commonality, but there it is.

Comments powered by CComment