- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A suggestive sketch

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

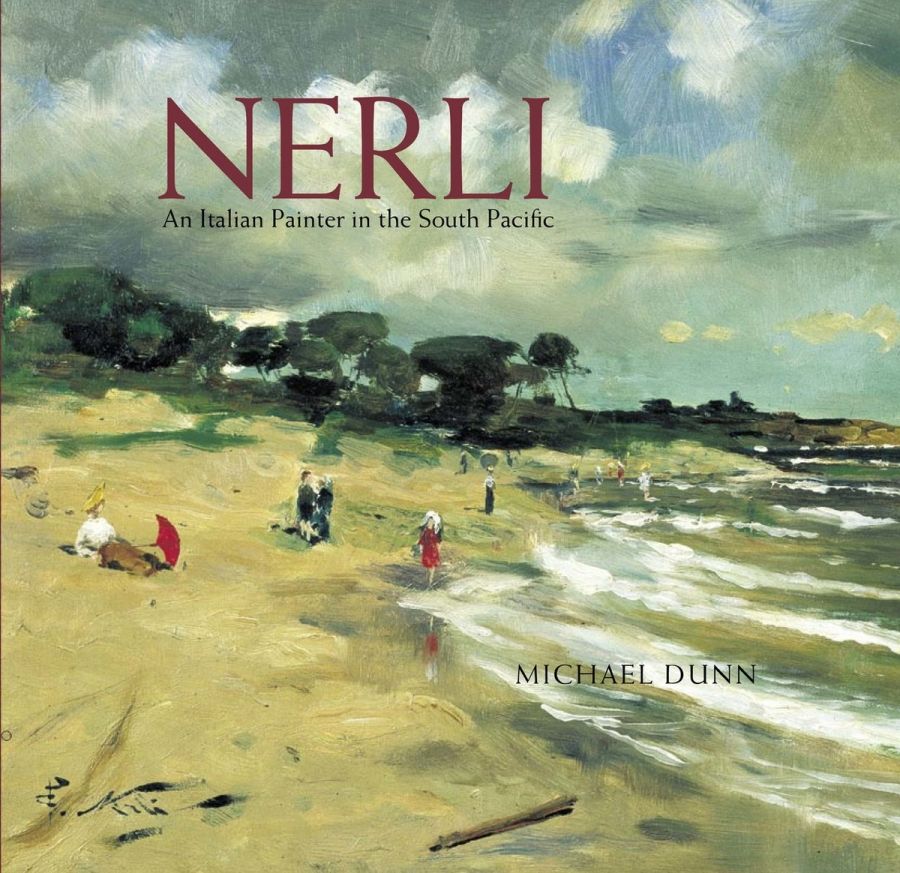

Girolamo Nerli, Michael Dunn writes in Nerli: An Italian Painter in the South Pacific, was ‘an uneven painter who ranged from the good to the downright bad’. It says much about the difficult development of the visual arts in Australia and New Zealand that someone with such apparently modest abilities should be worthy of such a lavishly illustrated and comprehensive study – especially in these days of constraint in art-historical publishing. Nerli has generally been depicted as a flamboyant Continental whose European heritage and thick Italian accent imbued him with an authority that made local artists and philistines alike listen receptively to his views. As a foreigner, he was permitted to be ‘irreverent, avant-garde and daring’, in ways denied local artists. Nerli’s place in Australian art history is assured by his association with the Heidelberg School artists, while his brief but influential role as Frances Hodgkin’s teacher secures his place in New Zealand’s art history. In this, the first published extended study of Nerli’s time in Australia and New Zealand (including a foray to Samoa), Dunn seeks a ‘fresh appraisal of the man and his achievements’.

- Book 1 Title: Nerli

- Book 1 Subtitle: An Italian painter in the South Pacific

- Book 1 Biblio: Auckland University Press, $79.95 hb, 160 pp, 1869403355

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Dunn, a New Zealander who studied art history at Melbourne University, has pursued his interest in Nerli since the 1960s, while developing a distinguished career as an academic. He has travelled to Italy, retraced the artist’s steps, discovered his surviving family members, located letters written by him, and, in short, fulfilled all the requirements one would expect of serious research. The product of this endeavour is a book which stands as an excellent example of art historical scholarship, with footnotes, references and appended material of great value to scholars and students of Australian and New Zealand art.

Maintaining his professional objectivity throughout, Dunn resists making inflated assertions about Nerli’s significance despite having invested so much of his time in the pursuit of the artist. Indeed, the opposite is true: he seems at pains to make no great claims for either Nerli’s art or his influence in the antipodes. Furthermore, he acknowledges that more research needs to be done to ‘document fully Nerli’s actual relationships with the Heidelberg painters’ and to produce a more accurate appraisal of the artist’s contribution to the art of Australia and New Zealand.

Impressively thorough in its documentation and detail, the book is usefully divided into two parts, the first of which provides biographical and historical background to the artist and his work. Dunn uses subheadings judiciously in this first section, ensuring that this is an accessible book for the reader or researcher wanting to focus on particular aspects of Nerli and his life or art. The second section consists of forty-one sumptuous coloured plates, organised in a loosely chronological order. Each image is accompanied by a commentary by Dunn. Finally, appendices of letters by Nerli and his wife, a comprehensive list of Nerli’s exhibitions in Australasia and a chronology of Nerli’s life add to the value of this work to students and scholars.

As a contribution to the field of art-historical study in Australia and New Zealand, this book is to be recommended, for the publication of art-historical works, especially with numerous colour images, is becoming increasingly rare. This book stands as an example of excellent scholarship and diligent, committed research, but it does not ‘sing’. It seems a little ‘overcooked’, as if the author has lived with the material so long that it has all become rather tired and familiar. The field of art history has also moved on substantially in recent years and, while not advocating a position that theory should drive all art-historical endeavour, there is so much in this material that cries out for a more theoretical analysis, even if such analysis is discretely embedded in the structure, rather than overtly displayed, if the publishers are concerned that theory may alienate the general reader. The book is thorough but plodding at times; occasionally even-handed to the point of being uninteresting. This is not to suggest that one should play with the facts to produce a more interesting story, but more analysis, more evaluation, would have made this a more engaging book. In commentary on the plates, for instance, less description and more interpretation, suggestion or information may have invigorated the images, which, to be honest, look clichéd to the contemporary eye.

In his evaluation of Nerli’s artistic reputation, Dunn restates his contention that more research needs to be done to determine ‘Nerli’s true significance’. In the meantime, he writes: ‘what we know of the man and his art resembles one of his sketches, suggestive and detailed in parts but obscure and unresolved in others.’ This accurately describes Dunn’s own writing, but his emphasis is on the detail, and this reader would have liked a little more of the vivid, evocative impression as exemplified by the artist in his best works.

Comments powered by CComment