- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Dangers of the deep

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

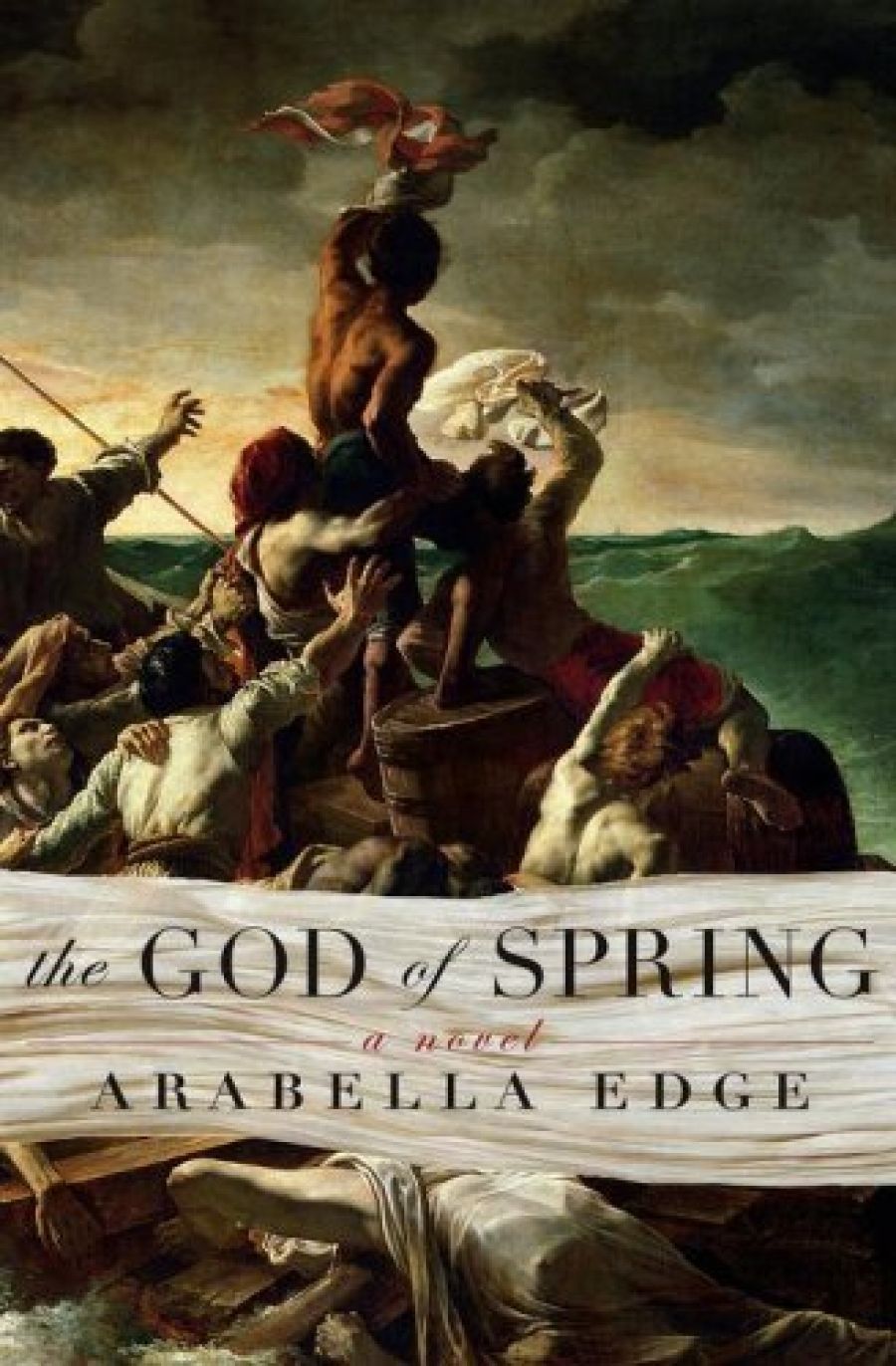

Disaster has always shadowed the traveller. Today’s adventurers differ from their forebears only in the kinds of calamity they have cause to fear. Arabella Edge’s second novel – like her first, the award-winning The Company (2000) – will have readers thanking their lucky stars that shipwreck, at least, has gone the way of history. As its cover suggests, The God of Spring centres on Théodore Géricault’s masterpiece, The Raft of the Medusa (1819) – its painting, its painter and the real event it depicts.

- Book 1 Title: The God of Spring

- Book 1 Biblio: Picador, $32.95 pb, 344 pp, 0330422065

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Just returned from Rome and on the lookout for ‘a subject that would set the world ablaze’, Géricault meets a disgruntled ex-Napoleonic colonel who spells out for him the significance of the cause célèbre the artist has missed whilst away: a ‘catastrophe’ that ‘represents a very microcosm of France’. In July 1816 the French frigate Medusa, on its way to re-establish the Senegalese colony, ran aground off the west coast of Africa. Insufficient lifeboats meant that 150 of the 400 voyagers were left stranded on a makeshift raft with few provisions and no navigational equipment. Only fifteen men were rescued alive when the raft was discovered thirteen days later. Géricault’s subsequent attempts to prise the true story of what happened out at sea from two of the survivors – the frigate’s surgeon and cartographer, Henri Savigny and Alexandre Corréard – becomes the novel’s primary focus.

That it takes Géricault so long to get the naked truth from these men – who become his gormandising house guests – ‘beggars belief’, to use a favourite fusty phrase of the author’s. Nonetheless, Edge skilfully and suggestively links Savigny and Corréard’s shipwreck tale to Géricault’s fight for artistic survival. The seamen’s reluctance to face up to the barbarous reality of their actions on the raft becomes the very thing upon which the artist’s success depends. The novel as a whole swirls around this Darwinian apophthegm: Sacrifice others, and thrive.

The genuine gravitas of the material and its treatment is belied by the novel’s beginning, however, which is less Patrick O’Brian than Barbara Cartland. When I was a child, I used to scour my mother’s romances for saucy bits, and found it so frustrating that they tended always to hide at some indeterminable place near the middle. It’s a pity this novel wasn’t around back then, because the bodice-ripping gets going almost immediately. The opening scene has Géricault hosting a dinner for his benefactor uncle, Charles Caruel, and mistress aunt, Alexandrine. Footsies and napkin-diving presage an urgent quickie in an alcove that is all over by the tenth page. It is a racy start that signals the author’s intent to marshal a wider readership, even though it’s clear by book’s end that the task pits her against her own more saturnine nature.

The God of Spring shares The Company’s sadistic bent, but has fewer literary pretensions. There is no ventriloquy, more dialogue (often too modern or too antiquated), and an increased pattering of reassuring clichés (losses ‘hang heavy’ like ‘portents’, for example). There are one or two glaring anachronisms: Géricault’s neighbour, the artist Horace Vernet, quotes a passage from Byron’s Don Juan in September 1818 that wasn’t actually published until July 1819, so far as I’m aware. But all in all, it comes as a relief that the novel wears its research lightly, and that it comes off as light and colour rather than studied authenticity. Edge has a talent for historical mises en scène. Her descriptions of pastoral Montmartre and pre-Haussmann Paris are evocative without threatening to swamp the tale being told. Despite the siren call of remarkable times, colourful bit-players and a romantic triangle, Edge holds her nerve and makes the painting itself the novel’s omphalos.

The God of Spring is classifiable as ‘artist fiction’, that boom genre of literary fiction, which is to the art world what the novelisation or film tie-in are to the movies. Seen the painting? Then buy the book. This fiction depends upon recognition and ignorance, upon our utter severance from the events of our collective past and our commendable desire to be reacquainted with them. Paintings are, as Francis Bacon said of antiquities generally, ‘remnants of history which have casually escaped the shipwreck of time’. The novelist finds her purpose in stitching up the details. To be sure, it is a kind of ‘painting by numbers’, which is why it’s not surprising that many of its best exponents, Edge included, are graduates of Creative Writing departments. After the mammoth success of Tracy Chevalier’s Girl with a Pearl Earring (1999), it’s hard not to see The God of Spring as a play for popularity and an angling after a movie option. But just as the Robert Southey couplet – ‘Tis pleasant by the cheerful hearth to hear / Of tempests and the dangers of the deep’ – used to advertise Géricault’s ‘great picture’ in the London papers fails to capture the experience of viewing it, so too The God of Spring cannot be dismissed as mere entertainment. There is something hard, cold and unsettling in its depths.

Comments powered by CComment