- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Reference

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Of no sect am I

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

For 175 years the Sydney Morning Herald has recorded the annals of colony, state and nation, never missing an issue. When the paper was established in 1831, the colony of New South Wales was still being opened up by exploration and settlement. Sydney’s population was little more than 15,000, while the colony itself numbered around 50,000 Europeans, including 20,000 convicts. Less certain was the extent of the indigenous population. To the first Australians, the Herald was initially unsympathetic. It called them savages and in 1838 campaigned against the trial and subsequent hanging of the men involved in the massacre at Myall Creek; to its credit, that view was soon recanted. In 2006 the Herald reflects the aspirations of the majority of Australians for a decent and just reconciliation with the Aboriginal people.

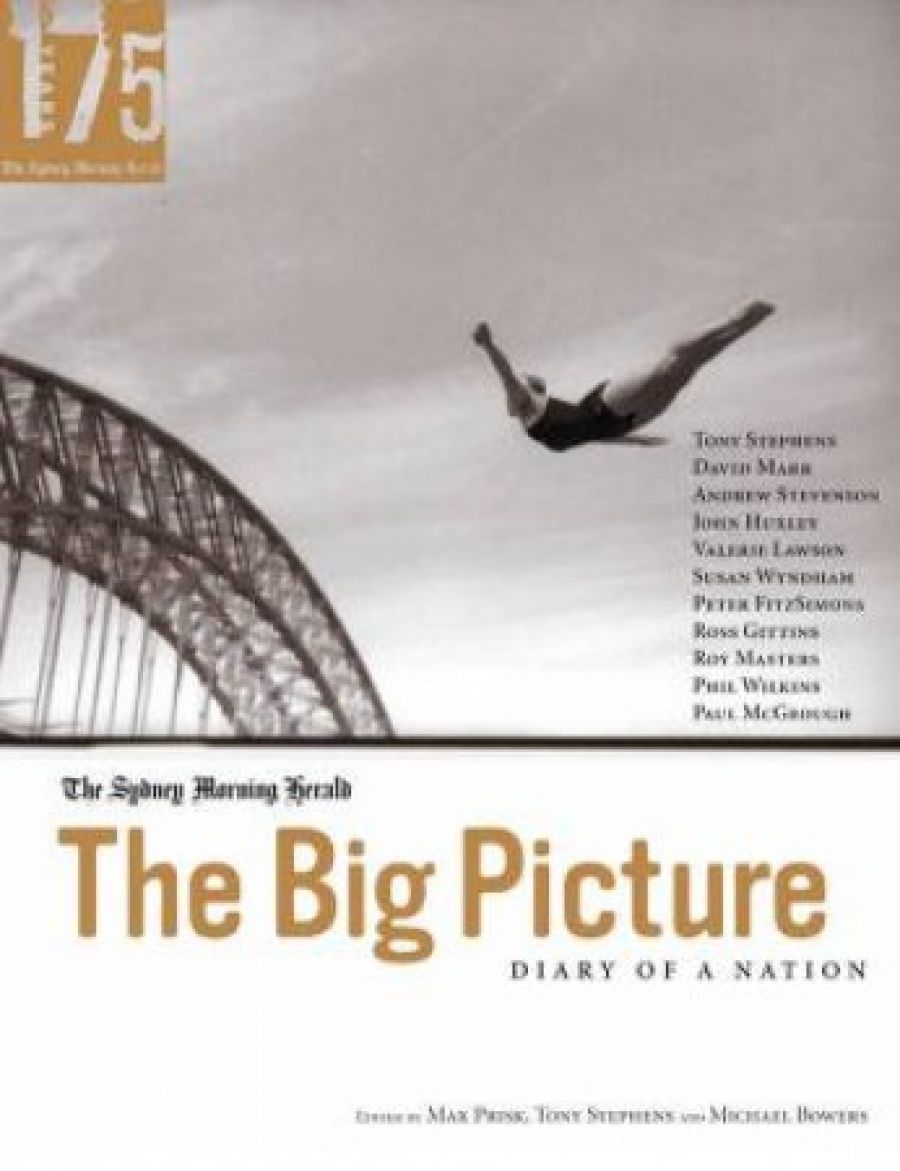

- Book 1 Title: The Big Picture

- Book 1 Subtitle: Diary of a nation

- Book 1 Biblio: Doubleday, $70 hb, 379 pp, 1864710985

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

For much of its history, the Herald’s natural home base was conservatism. It was especially slow to recognise the aspiration for homosexual law reform. On Monday, 26 June 1978, immediately following Australia’s own version of Stonewall, when gays and lesbians marched in solidarity and defiance along Darlinghurst Road prior to a mass of arrests, the Herald carried no report of the riots. In his memoirs published in 1997, Peter Blazey recalled that the ‘pompous Sydney Morning Herald refused to acknowledge what had happened at all’. The next day it added injury to insult when it named fifty of those who had been arrested but freed. As Blazey said, this inconsiderate mass outing ‘caused a great deal of pain’. Still, despite aberrations and blind spots, the Herald built its reputation on even-handed reporting. Its early motto, ‘sworn to no Master, of no sect am I’, drove it to seek balance and to analyse on merit the policy of all parties. Today, arguably, it is one of the most liberal and broad-minded of Australian newspapers, even if, too often, it indulges its local readers in an uncritical celebration of Sydney as the natural heart of Australia.

Fortunately, this commemorative book takes a broader view. In a series of thematic essays by leading Herald journalists – among them Ross Gittins, Valerie Lawson, Paul McGeogh, David Marr and Susan Wyndham – there is a blending of the local and the particular with the larger themes of the nation itself. And reflecting the place of Australia in the globalised village of the twenty-first century, the book illustrates the Herald’s ongoing commitment to the reporting and analysis of international affairs. McGeogh, who has given Australian readers some of the frankest and most fearless accounts of the war in Iraq, offers an especially thoughtful essay on the changes in the reportage of war and of peacekeeping over more than 100 years. After the carnage at the Dardanelles in April 1915, it took more than a week for C.E.W. Bean’s first Gallipoli dispatch to pass through the maze of telegraph and censorship. But as the Twin Towers of the World Trade Centre imploded on 9/11, McGeogh’s own copy was dictated direct to Sydney on a mobile phone line kept open all night. Minute by minute, as the horror unfolded and the world changed forever, McGeogh was able to update his account to feed each barely comprehensible development of that previously unimagined crisis into each of the Herald’s seven special editions.

But the real strength and delight of this book is its selection of illustrations and photographs drawn from the Herald’s unsurpassed photo-journalism library. With more than two million images, some going back more than 100 years, this library is the largest pictorial archive of its kind in the southern hemisphere. As the Herald’s editor-in-chief remarks, if the paper’s words are important and a vital part of the nation’s historical record, its photographs are indelible. As nothing else, they bring the past vividly to life. In war and peace, in moments of triumph on the sporting fields of the nation, in times of loss and tragedy, in the cut and thrust of politics, and in the abundance of cultural achievement, the Herald’s unequalled photographs evoke the past – those brief telling moments of time. My own eye was caught by the face of Prime Minister Robert Menzies being escorted through the crush of union protesters at Wollongong in 1939. This was the year he was derided as ‘Pig Iron Bob’ for his policy of allowing scrap metal exports to Japan. Yet the expression on Menzies’ face is a mix of courage and determination with an acknowledgment that, in the Australian democracy, protest has its own legitimacy.

Tony Stephens remarks that history rarely looks like history to people living through it. Even the most compelling press photographs and cartoons are generally taken for granted, briefly remarked on or as quickly passed over before the paper is dispatched to the recycling bin. But viewed retrospectively in the generous selection offered in this book, they have a potency that brings the past to life and that links our shared past as Australians to the present and to the future.

Comments powered by CComment