- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Illuminated marvels

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

To commemorate the centenary of Alfred Felton’s death in 1904, the National Gallery of Victoria and Macmillan Art Publishing have published the five illuminated medieval manuscripts and the single leaf ac-quired for the Gallery through the Felton Bequest. This stunning volume is profusely illustrated with colour plates taken by the photographic team of the NGV of all the decorative features in the manuscripts; in addition, there are numerous coloured figures of comparative works in other collections. Decorative elements from each Felton manuscript ornament the opening pages of each section, and embellish the title and end pages of the book. In design and illustration, this volume is itself a work of art, with hundreds of coloured images to delight the eye.

- Book 1 Title: The Felton Illuminated Manuscripts in the National Gallery of Victoria

- Book 1 Biblio: Macmillan and the National Gallery of Victoria, $66 pb, 439 pp, 1876832959, $99 hb, 1876832460

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

This is not just a picture book, however. Emeritus Professor Margaret M. Manion has written a readable and scholarly analysis of each of the manuscripts. The text is informative and interesting. While based on earlier research in Margaret Manion and Vera Vines’s The Medieval and Renaissance Illuminated Manuscripts in Australian Collections (1984), this book discusses more recent scholarly work and presents new insights into the significance of the art. Occasionally, the author also points to questions that need further investigation, such as the connections between the artists who illustrated The Melbourne Livy.

The manuscripts have illuminations of the highest quality. The earliest is a twelfth-century Byzantine work, The Gospel Book of Theophanes (Tetraevangelion), made in Constantinople (c.1125–50). From Lorraine in Northern France comes The Aspremont-Kievraing Hours (c.1300). The Melbourne Livy (c.1399) and The Wharncliffe Hours (c.1475–80) are the work of Parisian masters. The Strozzi–Accaiuoli Hours was produced in Florence in 1496, probably as a wedding gift. There is also a single leaf derived from a Universal Chronicle, perhaps by a French illuminator in Naples (c.1440–70).

Manion begins with some remarks on the Felton Bequest, citing John Poynter’s Mr Felton’s Bequests (2004). She then examines each manuscript separately and in chronological order, from The Gospel Book of Theophanes to The Strozzi-Accaiuoli Hours; she ends with the single leaf. In each section, Manion first highlights important features in the manuscript. She discusses significant imagery, decorative elements, the patron(s) and artist(s), the work’s provenance and entry into the NGV, and manuscripts by the same artist or workshop elsewhere. She then analyses the painting on each illuminated page. Finally, for each manuscript there is the scholarly apparatus of a specific bibliography, a summary physical description, and endnotes. There is a general bibliography at the back of the book.

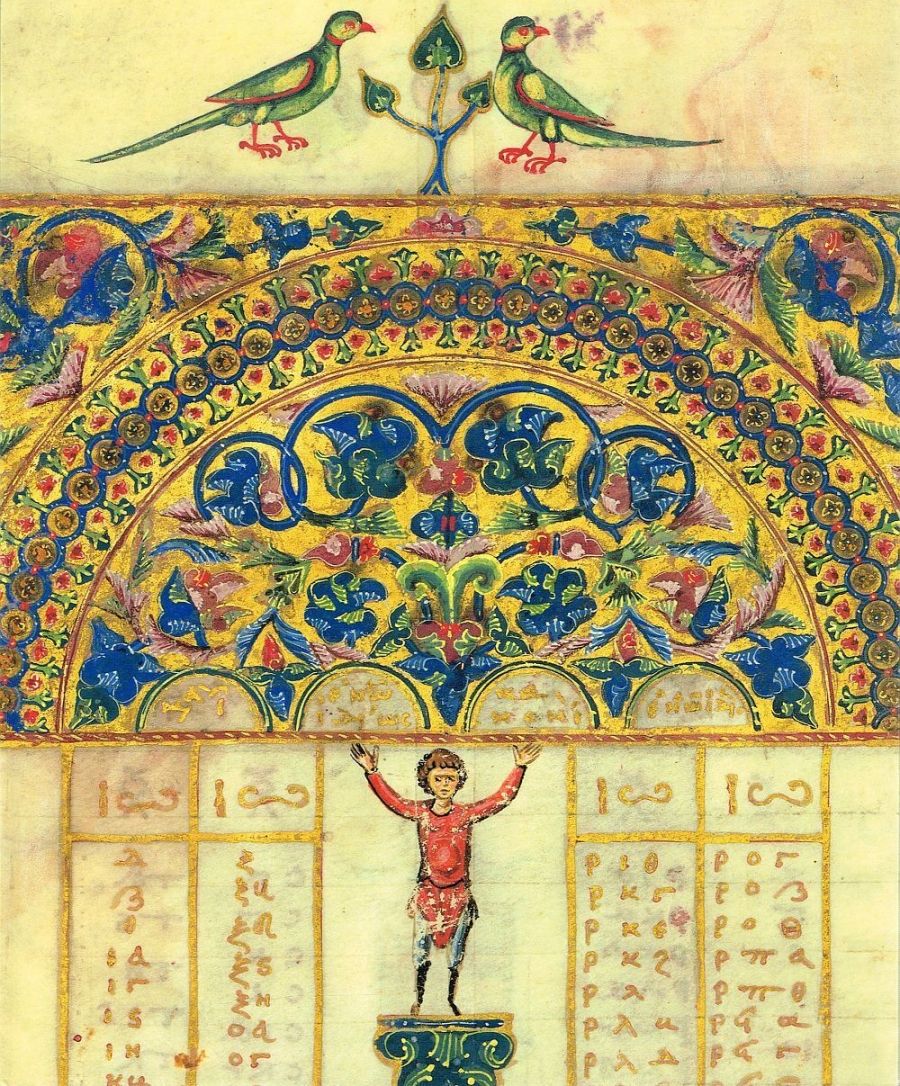

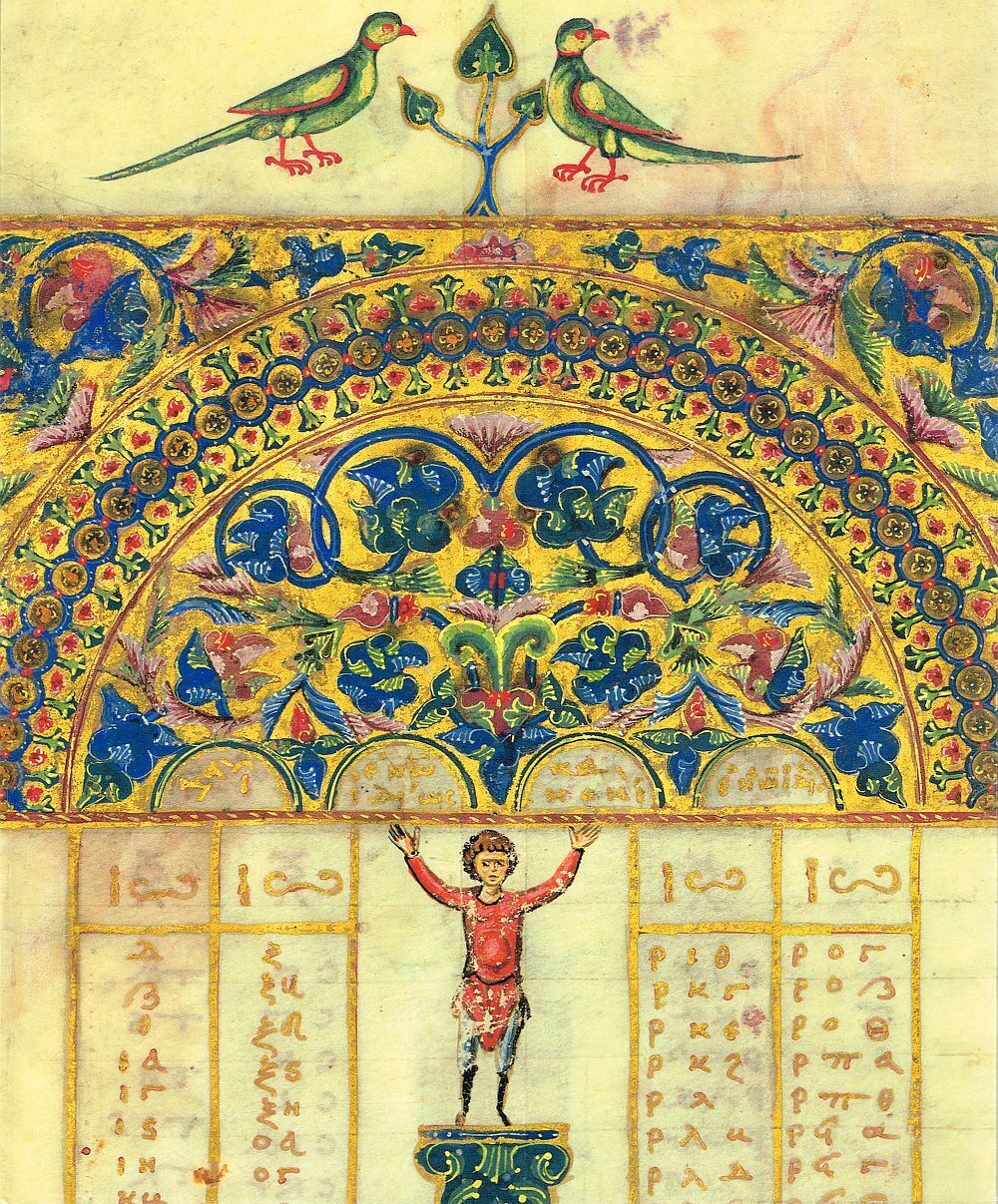

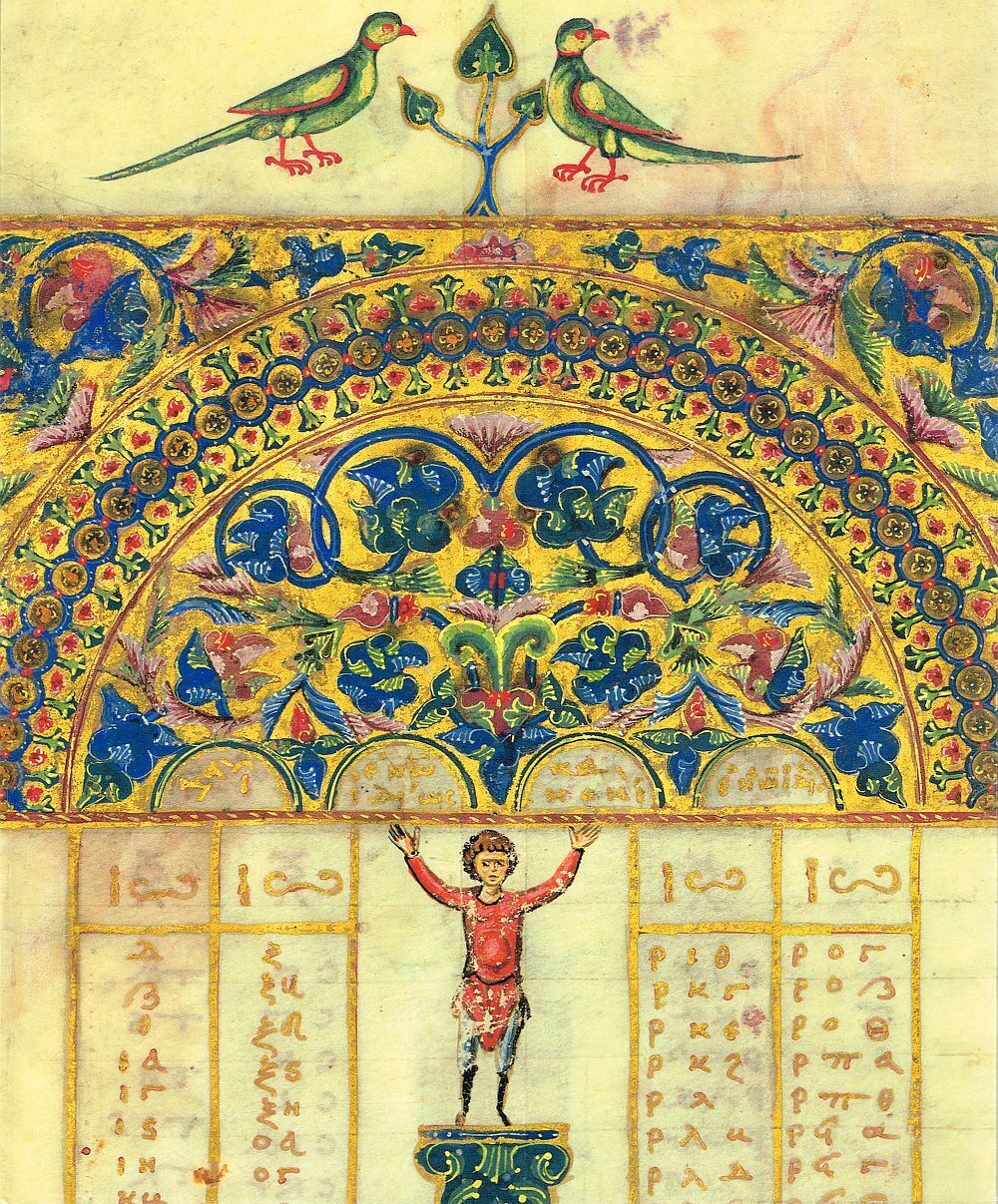

Some highlights of this volume demonstrate the variety and importance of the Felton manuscripts. The Byzantine Gospel Book of Theophanes (Tetraevangelion) has an unusual frontispiece, in which the scribe–illuminator monk Theophanes presents his volume to the Holy Mother of God and the Christ Child. A poem written in gold letters identifies him. The text of the four Gospels follows the Letter of Eusebius on the harmony of the gospels and a series of Canon Tables arranged under arches, with headpieces ornamented with blue, red and green vegetal motifs over a gold background. Small birds flank central motifs above the headpieces and lively figures stand above the columns. The latter portray the Labours of the Months and an interesting collection of Virtues, such as Thought, Knowledge, Judgment, Almsgiving, Well-doing and Kindness of Heart. Comparisons have been made with other Byzantine manuscripts, especially the Venice Gospels, which closely resembles the Melbourne work.

Among the three Books of Hours in the collection, The Aspremont–Kievraing Hours, written and illuminated around 1300, is transitional in form, while The Wharncliffe Hours and The Strozzi–Accaiuoli Hours have the developed text in Roman usage. The Book of Hours was a lay person’s prayer book. Typically, it included the Little Office of the Virgin, the Penitential Psalms, the Hours of the Cross, the Hours of the Holy Spirit and the Office of the Dead, as well as gospel lessons, and prayers to various saints. The Aspremont–Kievraing Hours, made by the scribe–illuminator Nicolas, has frequent images of its owners, Joffroy d’Aspremont and his wife, Isabelle de Kievrang. Historiated initials are filled with scenes from the life of Christ and the Virgin, or images of lay devotion, while pages are framed with bars of foliage and lively marginal figures. Among the marginalia, there are interesting images of animals and drolleries. Some animals and hybrid creatures are pictured in whimsical poses, or acting out fables, or the medieval animal lore of the Bestiary. There is a companion volume, The Aspremont–Kievraing Psalter, in the Bodleian Library in Oxford.

The Wharncliffe Hours is a masterpiece of the Parisian illuminator Maître François. In the introductory calendar, amid the floral spray borders, the signs of the Zodiac and the Labours of the Months embellish the page for each month. Particularly fine scenes from the life of the Virgin and of Christ, often with figures in grisaille, are set in verdant landscapes. These pictures are surrounded by subsidiary or contrasting figures in the borders, or at the bottom of the page. The Office of the Dead is introduced by ‘an arresting miniature’ of The Three Living and the Three Dead, in which three young noblemen meet three skeletons, who remind them that all must die and that they should amend their ways. The frame of this macabre scene is filled with leafless branches, in which sit two figures dressed in black, and at the bottom of the page is a cemetery, with a new grave prepared. Among the prayers to saints there are images of Saint Christopher, patron of travellers, and Saint Sebastian, who was invoked for protection from the plague.

The style of the Florentine Strozzi–Accaiuoli Hours is very different, both in its humanistic script and in the miniatures and borders painted by Gherardo (1445–97) and Monte (1448–1532/33) di Giovanni di Fora of San Miniato. The main parts of the book are prefaced by exquisitely painted double-page openings, with a miniature on one side and on the other a historiated initial and gold text over a red, blue or green background. The border decoration of these pages includes dolphins, sphinxes, centaurs, masks and acanthus scrolls derived from classical ornament. To accompany The Crucifixion, which introduces the Hours of the Cross, there are two popular devotional images, the Man of Sorrows and the Pietà. A Franciscan friar, holding a skull, and a skeleton are depicted at the base of the frontispiece to the Office of the Dead, where the Raising of Lazarus is pictured. A gold monogram ‘IHS’ occupies a central roundel in the upper border on ff. 13v, 14, 103v and 104. Manion explains that these are ‘the first letters of the name of Jesus’. The frame of golden rays around the letters was used by Saint Bernardine of Siena, a famous Franciscan preacher of the early fifteenth century, one of several Franciscans featured in this manuscript.

Pierre Bersuire’s translation of Livy’s History of Rome (c.1399), is one of a large number of manuscript translations of classical literature made in France. Book producers and dealers, libraires, appear to have organised artists and workshops across town and country to carry out the writing and illumination of such books. Two artists clearly worked on this manuscript, which is illustrated with numerous scenes in quatrefoil frames. As in similar works, the images illustrating the text are set within the artistic conventions of medieval France. The battle scenes depict knights in armour, while Roman senators and priests wear the dress of medieval French kings, nobles and bishops. The representation of the shepherd Faustulus finding the twins, Romulus and Remus, has the babes beside the she-wolf of Rome wrapped in swaddling clothes, like Christ in the adoration of the shepherds at Bethlehem.

The single leaf depicts nine famous men, from a series of figures deriving from a universal chronicle and frescoes painted in the Roman palace of Cardinal Giordano Orsini (c.1432), which does not survive. Although Vasari attributed the frescoes to Masolino da Panicale, modern authorities attribute them to other artists.

This book has a list of figures (of the comparative material), but there is no list of plates (of the manuscripts in the NGV). Often there are numerous plates of the decoration of each page, but they all have the same plate number, although some plates are distinguished as a ‘detail’. Because of this, the reader can find it difficult to locate the plate referred to in the text. Different enumeration and a list of plates would alleviate this problem. Occasionally in the text, endnotes are not provided after quotations. Despite these minor problems, this is an excellent book.

When the Felton manuscripts are on show at the NGV, viewers can only examine a maximum of two pages at a time. In this volume, they have access to fine coloured reproductions of all the significant imagery in all the manuscripts, as well as to Margaret Manion’s authoritative text.

Comments powered by CComment