- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Sitting-duck time

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Australian folk memory of the Pacific War centres on specific events – the sinking of the Repulse and the Prince of Wales, the fall of Singapore, the bombing of Darwin – events overlaid by semi-mythical visions of an insomniac prime minister and his cable wars with Winston Churchill, and of epics of soldierly endurance on the Kokoda Trail. The horrors of the Thailand–Burma railway belong, in a sense, to the immediate postwar period, when the stories of liberated survivors penetrated the national consciousness. The horrifying images of emaciated men with gaunt faces and prominent ribs brand that generation and, to some extent, their children. In the diaries of Weary Dunlop and in Rohan Rivett’s Behind Bamboo (1946), the immediate postwar Australia was given a vivid picture of Japanese cruelty and Australian suffering.

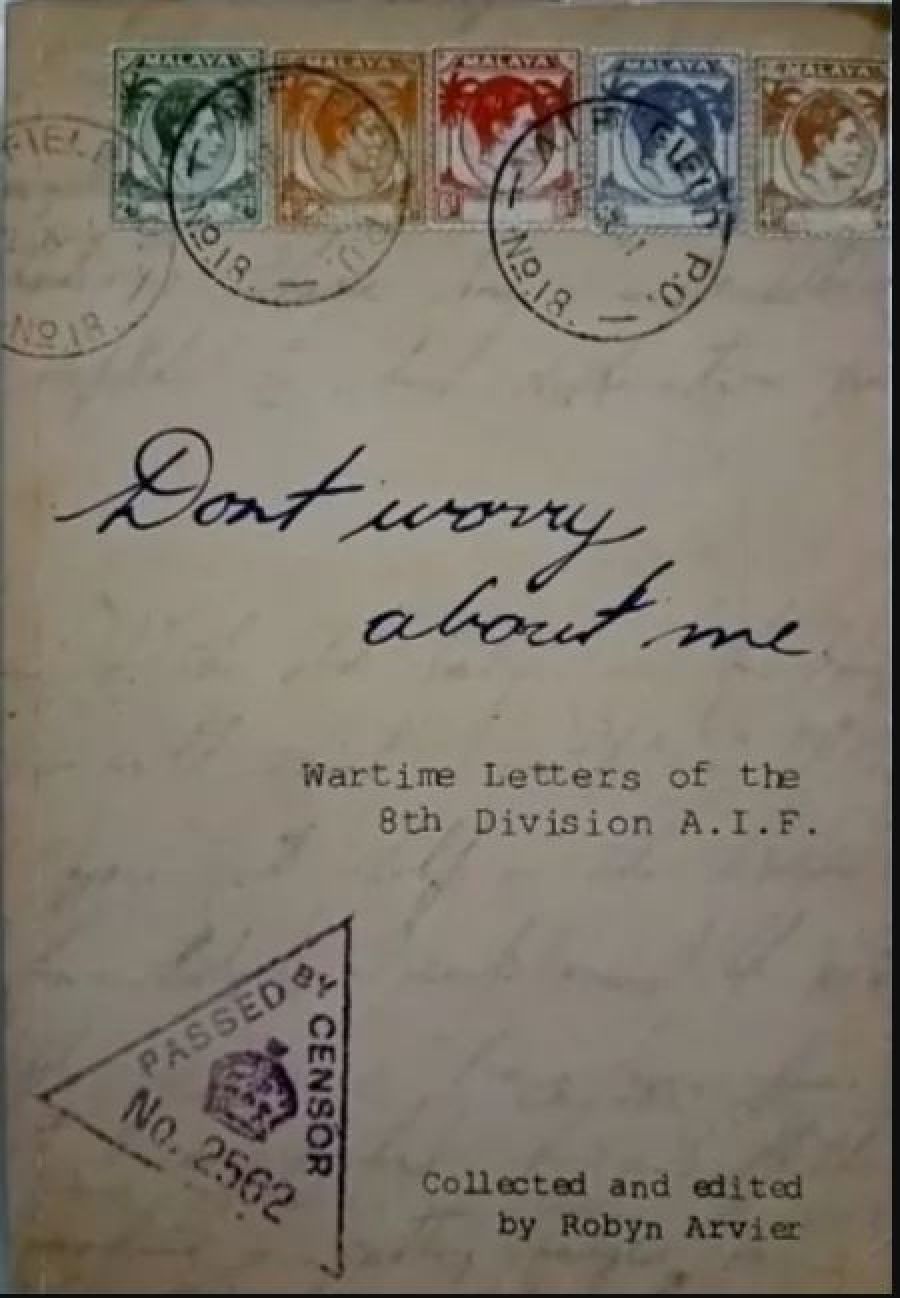

- Book 1 Title: Don't Worry About Me

- Book 1 Subtitle: Wartime letters of the 8th division AIF

- Book 1 Biblio: Robyn Arvier, $24pb, 226pp, 0 646 44026 8

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

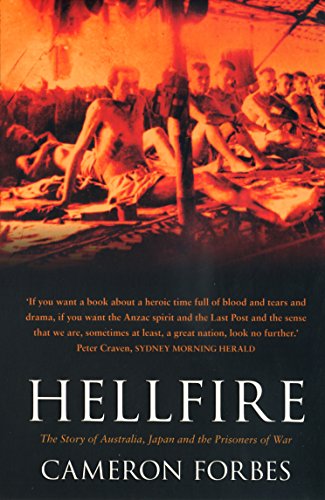

- Book 2 Title: Hellfire

- Book 2 Subtitle: Australia, Japan and the prisoners of war

- Book 2 Biblio: Pan Macmillan, $45hb, 560pp, 1 4050 3650 8

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

‘There is nothing glamorous about the AIF,’ commented Sergeant Geoff Riach, and I think his comrades would have agreed with him. Private Jack Leu wrote to his father: ‘Did old Eddie get in the Army yet, tell him from me to stay home she is no cop when it starts to get fair dinkum.’ Darcy Perceval writes the obligatory, ‘we are ready if anything starts,’ but then adds, presciently, ‘I don’t know how long we will last if they do start on us. Because in the jungle you cant see them coming till they will be right up against you.’ All three of these men died in the war.

What happened was that Japanese forces landed on the Isthmus of Kra and at Kota Bharu on 8 December 1941. The British command in Malaya had come almost to regard the jungle as impenetrable, overestimating the importance of roads. The Japanese, employing sound and aggressive tactics and enjoying command of the sea, provoked a chain reaction of Allied uncertainty and ‘ordered retreat’. When General Percival surrendered Singapore to General Yamashita on 15 February 1942, 130,000 Allied troops became prisoners of war, including 15,000 Australians.

The Japanese attitude to prisoners has been much discussed. People have written of the dishonour, in Japanese eyes, of surrender. ‘We all talk about fighting to the last man and the last bullet,’ observed General Sir William Slim. ‘The Japanese soldier was the only one who did.’ Surrender in battle was a shameful deed in the Japanese military code, and it is clear that the Japanese regarded these Allied troops as dishonoured men who, because their lives had been spared, should cooperate with them, as if they had changed sides till the end of hostilities, as in feudal times. This attitude explains why officers and non-commissioned ranks were interned together, a decision which, by preserving unit organisation, undoubtedly helped to maintain the prisoners’ morale over the terrible years ahead.

The existence of many thousands of fit, though unarmed, enemy soldiers near the field of operations was intolerable to the Japanese command, and an ingenious solution was quickly found. It was decided to use the captives to build a strategic railway linking Bangkok in Thailand with Moulmein in Burma. Both countries could provide sufficient rice to feed the prisoners, who would be isolated hundreds of miles from any battle zone.

Cameron Forbes purports to tell their story in Hellfire, although much of the book discusses other topics, such as the Malayan campaign itself and the Australian experience in the Dutch East Indies. In these sections, Forbes provides the almost ritualistic Churchill-bashing of Australian war histories, but offers nothing new or illuminating. He takes a superior tone with the Japanese historian Masanobu Tsuji, rather than attempting to comprehend his point of view: ‘With his usual understatement, Tsuji says Watanabe carried out his duties like a war god.’ Forbes is also very sure of his military judgments, a confidence I would be more inclined to share if he hadn’t, for example, made the common mistake of assuming that the Japanese Imperial Guards Division was equivalent to its Napoleonic namesake, when in fact it was a ceremonial unit pressed into service because of the shortage of Japanese troops in the region – rather as if the British had put the Buckingham Palace Guards on the active list. Forbes has some interesting things to say about General Bennett, the commander of the 8th Division, but they do not appear to be supported by adequate research or reflection.

The prose can be atrocious: ‘We are talking frying pan and fire here’, and ‘It was sitting-duck time’. The book lacks a sense of accumulation, and I missed the feeling of the transitions – from homeland to jungle, from jungle to bombed city, from bombed city to Changi, from Changi to ship, from ship to boxcar, from boxcar to labour camp – that must be evoked to allow the reader access to the men’s experience.

The gestures towards understanding the Japanese perspective are merely that, gestures. Forbes quotes Kenji Ueda, a sort of Japanese Keith Windschuttle: ‘Isn’t it a fact that the West with its military power invaded and ruled over much of Asia and Africa and that this was the start of East–West relations? There is no uncertainty in history. Japan’s dream of building a Great East Asia was necessitated by history and it was sought after by the countries of Asia.’ Without doubt, Kenji Ueda is deluded, and offensively so, but the first sentence of the quotation is accurate and Forbes’s tendentious presentation displays exactly the same insularity and arrogance he invites us to dismiss.

The generation that survived World War II knew that no difference, no irritation, no ideology, was worth a war. While not magically transformed into benign and loving beings, what that wartime generation experienced was too terrible not to teach them something. Now, as they die out and as their successors forget, war has again become permissible. The memory of the men of the Second AIF is even invoked to support these ‘just’ conflicts. It is a disgrace to their memory. Non-combatants argue for war: men who have fought seldom do. It is incumbent on the historian, therefore, to be careful.

I don’t think Forbes has been sufficiently careful. Without falling into the fatuities of moral equivalence – how is it possible to discriminate between levels of suffering? – my thoughts, when reading Hellfire, kept straying towards Tokyo, where on 10 March 1945 forty per cent of the city was razed by a fire-bombing raid that killed and wounded nearly 100,000 civilians and that left a further 375,000 homeless. (Forbes does refer to this crime in his book.) The ‘they started it’ line is morally cretinous. What the Japanese suffered should not be forgotten, any more than what they did to their Allied prisoners should be forgotten. But on the evidence of Forbes’s book, we are forgetting and sliding easily into the self-justificatory simplicities that presage aggression and death.

Comments powered by CComment