- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The heart of imagery

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

A number of the poems in Lidija Cvetkovic’s first book stem from revisiting places and people in the war-torn country of her birth, the former Yugoslavia, but the poetry springs from an interrelated heritage. An Eastern European sensibility guides this poetry, informing and being informed by laconic Australian understanding. Poems that speak of ethnic and regional conflict, and of self, lovers and family in two continents, are woven into the same breath; and as the inexplicable in human experience is measured, a quiet celebration of human resilience can be heard.

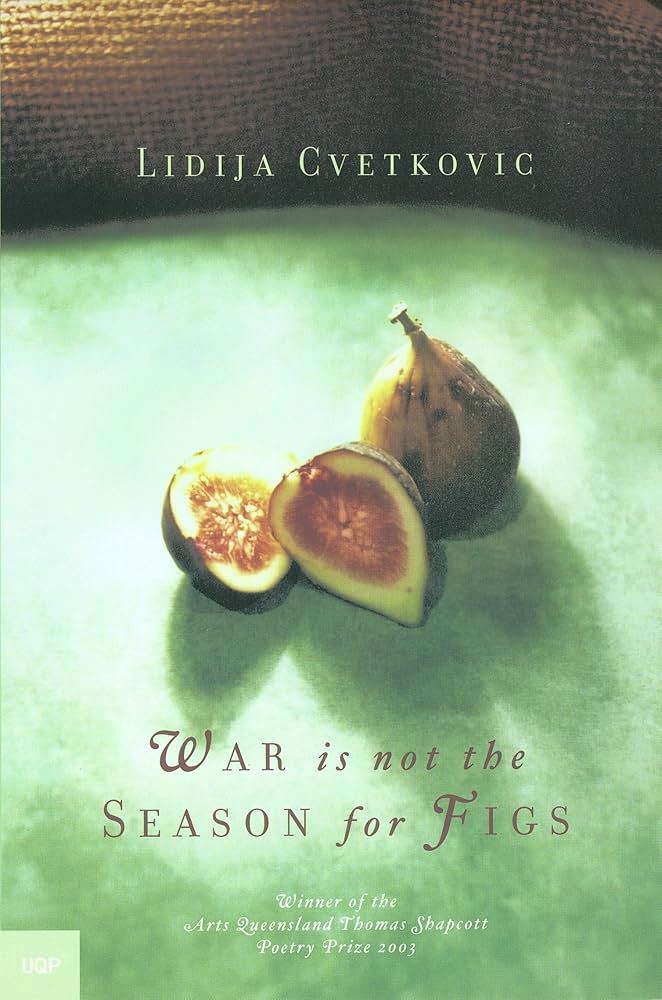

- Book 1 Title: War Is Not the Season for Figs

- Book 1 Biblio: UQP, $22.95pb, 74pp, 0 70223 484 2

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Title: Modewarre

- Book 2 Subtitle: Home ground

- Book 2 Biblio: Spinifex Press, $24.95pb, 90pp, 1 876756 50 0

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

The figs have shrunk in size

they lie beneath neon lights – cold, shrivelled, green.

War is not the season for figs.

Only fools offer their hearts on a palm.

Offering poetry on a palm? Yet not without an awareness of its slipperiness. ‘Reliable Magic’, for example, mischievously jests about various forms of contraception, speaking of charms, magic and ritual. The quirky final line, ‘once inside reliable, catch it if you can’, teasingly acknowledges the unreliability of cultural methods (‘honey mixed with dates’, ‘a gold wishbone, or silver ring’) and, equally, the elusiveness of poetic truth.

Cvetkovic uses imagery with clarity and grace. Figs become a metaphor for the body, just as easily split open. Elsewhere, recurrent images of honey, nectar and seeds become a regenerative force, guiding the poet’s reflections on love, mortality and transience, as in ‘Oodgeroo’, ‘The Process of Separation’ and ‘A Seed, a Crutch, a Heart’. In ‘A Portrait of My Father’, such imagery is fused with a father’s anguished response to television reports of conflict: ‘a voice fires … massacres mass graves / like bullets into our lounge room / shooting father. Blood / thick as honey runs along / his fragile frame.’

‘Observations on Three Varieties of Snowfall’ is and is not about snowflakes. The surprise of metaphor is what strikes you in this poem: lightly touching on snow imagery, suddenly this sequence also becomes a meditation on weapons of war: the land mine (‘If hordes walk over it / it takes revenge. / Dangerously compact / it can crack heads’); and the air-raid bomb (‘It falls voluminously. / It falls like plumes or ash. / It can be found on the tongues of children / or on the threshold of an eyelash’).

The imagined conversation with a great-grandmother in ‘Severed’ seems fearfully apprehended, and marked by a poetic refusal to cave in. This poem delves into precarious situations, a difficult life pursued with age-old cultural tensions (‘We trusted neither land nor sky / and prayed and crossed ourselves / whenever in the open’), made more difficult by assault within the home (‘I faced the next day split as a fallen fruit, plum-blue’). The tone is foreboding; the story, which is utterly confronting, pivots on an inviolable act of survival. The gravity in the rhythm meets the gravity in the dialogue, yet a lightness in the choice of words lifts this poetry, playing into a space of primal empathy and care. A similar space is created in ‘The White’, a moving contemplation of a father’s illness.

Cvetkovic presents crafted, self-assured poetry, which transforms raw experience of the personal and the political into works of enduring strength.

We know from the opening poem in Modewarre: Home Ground that Patricia Sykes’s poetry will be delving into political and historical issues. Links are attempted between ‘Modewarre (the indigenous)’, ‘biziura lobata (the colonial)’ and ‘musk duck (the common)’:

the ducks refreshed in their feathers

disturbed into moving on

in such safety as is theirs

their waters still historical

still urgent to be read.

Key words here evoke empathy and resound with good intent. Yet if the musk duck, and its activities, are meant as an allusion to indigenous life or to encounters with white people, then the link is only vaguely made, and the aim breaks down into prose observation: ‘the female musk duck is busy / feeding her single young / ... the swans on irritated / surface patrol forcing her / to combine evasion with the hunt’ and ‘one moment the dive / then the drift to safe water / a haven among water lilies.’ The hint of tension between species in these lines remains unrelated to the commotion of colonial history.

Occasionally, a connection between history and the musk duck looks promising, as in ‘toxic, kiss’: ‘Modewarre, how far were you / from the poisoned flour / the water laced with arsenic?’ Mostly, though, the images simply press buttons of emotion. This poetry seems uncertain about where it wants to take the reader: ‘the duck itself wishes to feed no surgery no medi care / sister, your belladonna is Italian somewhere else, where / Mussolini lived.’

Parts of ‘espionage with duck’, ‘visa as pessimist’ and ‘dis-locations ... a polemic’ present some good lines. Try also the opening of ‘three years in a flooded paddock’:

the tussocks so at home

they pass through the wind

as if rustle and click

is the language of clarity

no word for such voices

but they’re reading you

in their plant-like way.

The assonance in these lines might catch attention when read aloud, and this style should appeal: it offers images that veer outward in hope of the unexpected moment of contemplation. However, the possibility of stillness is thwarted: what we have is an endless whirling of images, a want of focused reflection.

Sykes’s book is packed with cascading images. While aiming towards the dialectic, this poetry falls short: too often poetic function is highlighted, with imagery only of interest in itself. This poetry requires further redrafting to catch moments of truth.

Comments powered by CComment