- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Custom Article Title: Michael Shuttleworth reviews four books

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Life is elsewhere

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Dreams of leaving can be a powerful force in the lives of young people. These four novels are each touched by the desire for other places. The idea that a more authentic self lurks beyond our familiar zones shapes these books, three of which are written by Australians, and one by an American writer who spends half his time in Australia and half in New York.

- Book 1 Title: The Running Man

- Book 1 Biblio: Scholastic, $19.95pb, 280pp, 1 86291 575 X

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

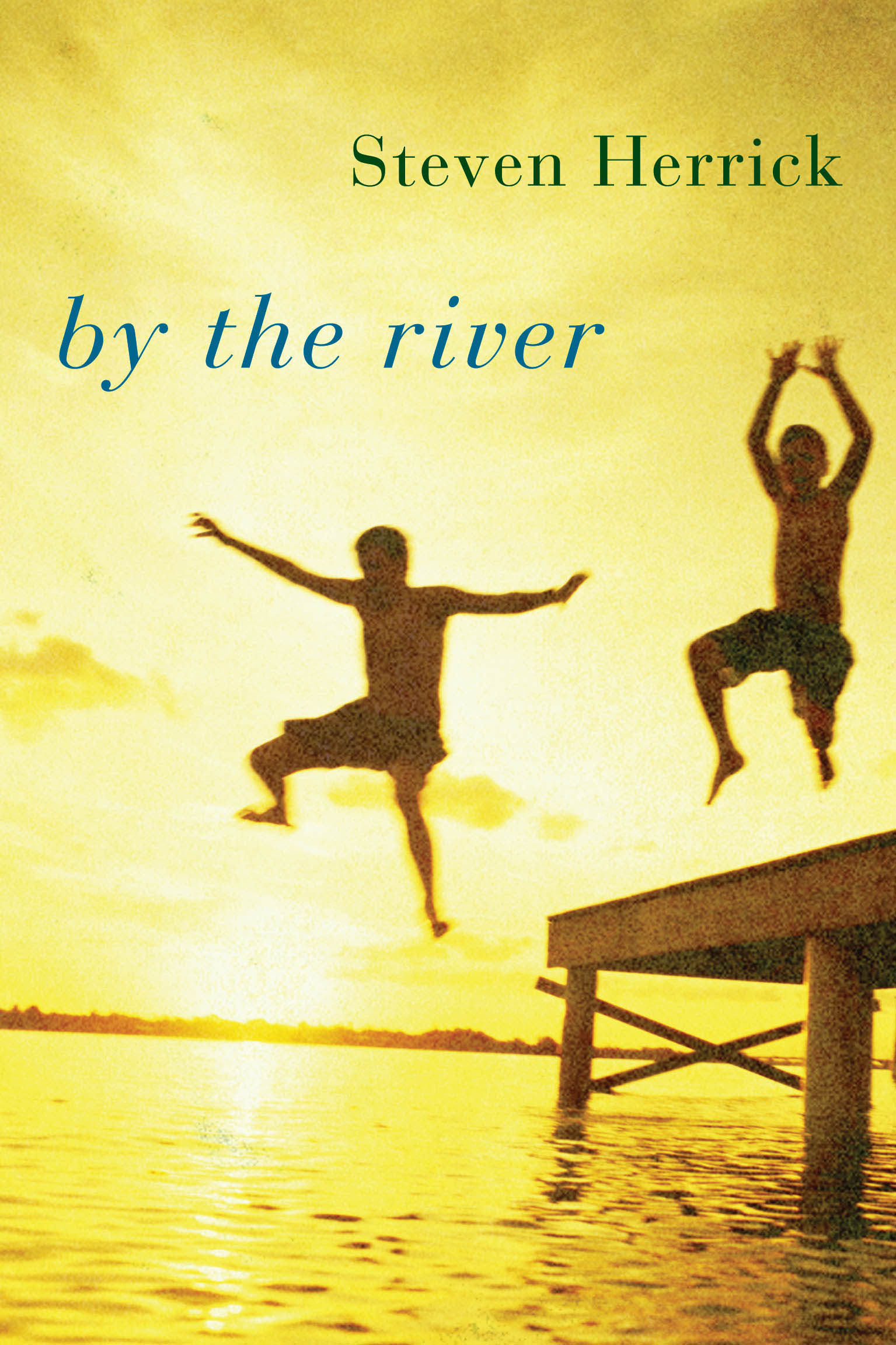

- Book 2 Title: By The River

- Book 2 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $16.95pb, 232pp, 0 74114 357 8

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 3 Title: Secret Scribbled Notebooks

- Book 3 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $17.95pb, 219pp, 1 74114 406 X

- Book 3 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 3 Cover (800 x 1200):

Secret Scribbled Notebooks, by Joanne Horniman, is a sophisticated and satisfying novel. Addressing the reader via her ‘secret scribbled notebooks’, Kate O’Farrell is determined not to fade away in the Lismore boarding house where she has grown up with her older sister Sophie and her ersatz mother, Lil, the owner of the boarding house. Kate is seventeen, bright and about to complete high school. Writers such as Virginia Woolf, Oscar Wilde, Leo Tolstoy and Charles Dickens fire her imagination. ‘I wonder if I read enough about the lives of other women whether I would find out how to live my own?’ she asks.

The book begins at full speed with the birth of Sophie’s child. While Kate is swept up in the excitement, the baby’s arrival underlines a potential trap for her, far from the centre of things. Each notebook reflects a different thread in Kate’s story. The red notebook has an immediacy that sharply encapsulates her desires. The blue notebook is for memory and records the fragile family relationships and Kate’s fractured childhood. Yellow is for dreams of a future in Sydney, where she would live the café life with Alex, a young man she has met in Lismore. ‘Wild typewritten pages’ carry the main narrative; Alex, who is struggling to write a novel, has gifted these to her. The novel explores Kate’s lived and imagined worlds, testing the bonds of family, Kate’s own hesitant desires, and the real world, beyond the close-knit, bookish one she knows.

Horniman’s strengths lie in her tender exploration of relationships, particularly between women; her vivid sense of place (the balmy northern New South Wales coast has a powerful and seductive presence); and the playfulness and control evident in her writing. In Kate O’Farrell, she has created a character who embodies all of these things.

Steven Herrick’s verse novel, by the river, takes place in the early 1960s in an unnamed country town. Herrick pulls off a neat trick in switching between past and present tense, the long view and the close-up. by the river represents memory distilled by time, and a not so fond farewell to an earlier Australia.

Harry Hodby’s hometown has devoured almost everything he loves. His mother died when Harry was seven; his friend Linda drowned in a flood; and Miss Spencer, with whom Harry has fallen in love at the age of fourteen, leaves town because of gossip and innuendoes. Harry burns to go, too. Without his mother, Harry is exposed early to the world and to its frequent injustices. His nemesis, Johnny Barlow, is the youngest brother of a rough clan that includes a criminal and a greaser. Harry learns what lies beneath the ugly exteriors of the town, while he and Johnny negotiate a delicate path that involves recollections of Linda, Miss Spencer and their respective families.

Harry’s father offers the emotional counterweight to the town’s casual cruelty. He works in a sheet-metal factory, sprayed by iron filings ‘so sharp it was like / getting tattooed / every day / for twenty years’. His father is also the one who shows Harry the way out of town and acknowledges the need to leave. While the mood of this book is frequently downbeat, it also bristles with life. For Herrick, it is a playground for language. Perhaps ironically, it is place and the love of the father that redeem this journey. The book also contains a number of excellent individual poems that fix on landscape as a source of memory and as a measure of time.

The most striking feature of Michael Gerard Bauer’s first novel, The Running Man, is its intense interest in the characters’ psychology. This is a distinctly inward journey. The eponymous running man, a ragged, restless and quite frightening tramp, haunts the dreams of young Joseph Davidson. Joseph lives with his mother in a mundane Brisbane suburb; his father is living and working elsewhere, evidently keen to be anywhere but at home. Tom Leyton, Joseph’s reclusive neighbour, has not ventured outside in a decade and is scarcely glimpsed through the windows of his house. Joseph finds himself drawn to the shadowy Tom when he accepts an invitation to draw a portrait of Tom for a school art project. This is partly in spite of the rumours that surround Tom (Joseph does it as a dare, arising from his own perceived timidity), and partly to buck convention in the narrow-minded neighbourhood. A classic relationship between the artist and the sitter develops.

The power roles oscillate wildly, since Joseph is clearly afraid of this brooding, intense and private man. The two are brought closer through the older man’s obsession with silkworms, the breeding of which provides both a structure for Tom’s life and a dark metaphor. At one point, Tom says of the silkworms: ‘They are born, they live and they die … They go on with their pointless existence in blissful ignorance until someone tosses them in a rubbish bin.’ The reason for this nihilism becomes clear as the relationship unfolds, revealing Tom’s despair and his disgust at the human world. The silkworm metaphor is heavily emphasised, threatening at times to overbalance the story. Bauer at times overwrites and the story is slow to unfold, but the resolution, with its lyrical mix of the realistic and the numinous, is genuine and affecting.

In Scott Westerfeld’s So Yesterday, Hunter lives in New York City, but it wasn’t always so. Now he is a ‘cool-hunter’, a trend-spotter for global brands; once he was just a mall-rat from Minnesota. When Hunter moved to New York, he became the least cool kid in school, drowning in a ‘billion coded messages being sent everyday with clothes, hair, music, slang’. Hunter meets Jen, another outsider from the suburbs. Jen is a Logo Exile who displays her otherness in ‘non-brand not too baggy jeans, rising-sun-laced runners and black T-shirt. A very classic look.’ Together, they are caught up in an artful and exciting piece of culture-jamming, an anti-marketing scam that involves the perfect sneaker. So Yesterday, an exceptionally entertaining story, reflects upon how we create our lives and identities via brands, labels and marketing. Through his attachment to Jen, Hunter is forced to confront his identity in the whirl of images and the carnivalesque chase through the ultimate elsewhere – hyper-modern New York.

Westerfeld is a new writer to Australian audiences, and we will see much more of him if So Yesterday, witty, pacy and intelligent, is anything to go by.

Comments powered by CComment