- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Settler Colonialism

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Missionaries, marxists and misfits

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Papua New Guinea is definitely not one of the grand colonial stories. There is no tradition of empire, no tales of the raj, to be glorified or excoriated by historians and other nostalgics. Mostly, the various German, Australian and Japanese colonial administrations were not infrequently racist and stupid, often brutal and overwhelmingly unimaginative. Australia’s colonising and neo-colonising of what has become PNG was always, and still is, principally focused on its security interests, not on bringing civilisation to noble savages or developing a thriving economy. The colonial Australians who ventured into the oppressive heat, spectacular mountains, awesome rainforests and malarial swamps mostly comprised parsimonious bureaucrats, rugged patrol officers, no-nonsense police, Christian evangelists, and fugitives of pretty well every kind – ‘missionaries, marxists, and misfits’, as the saying goes.

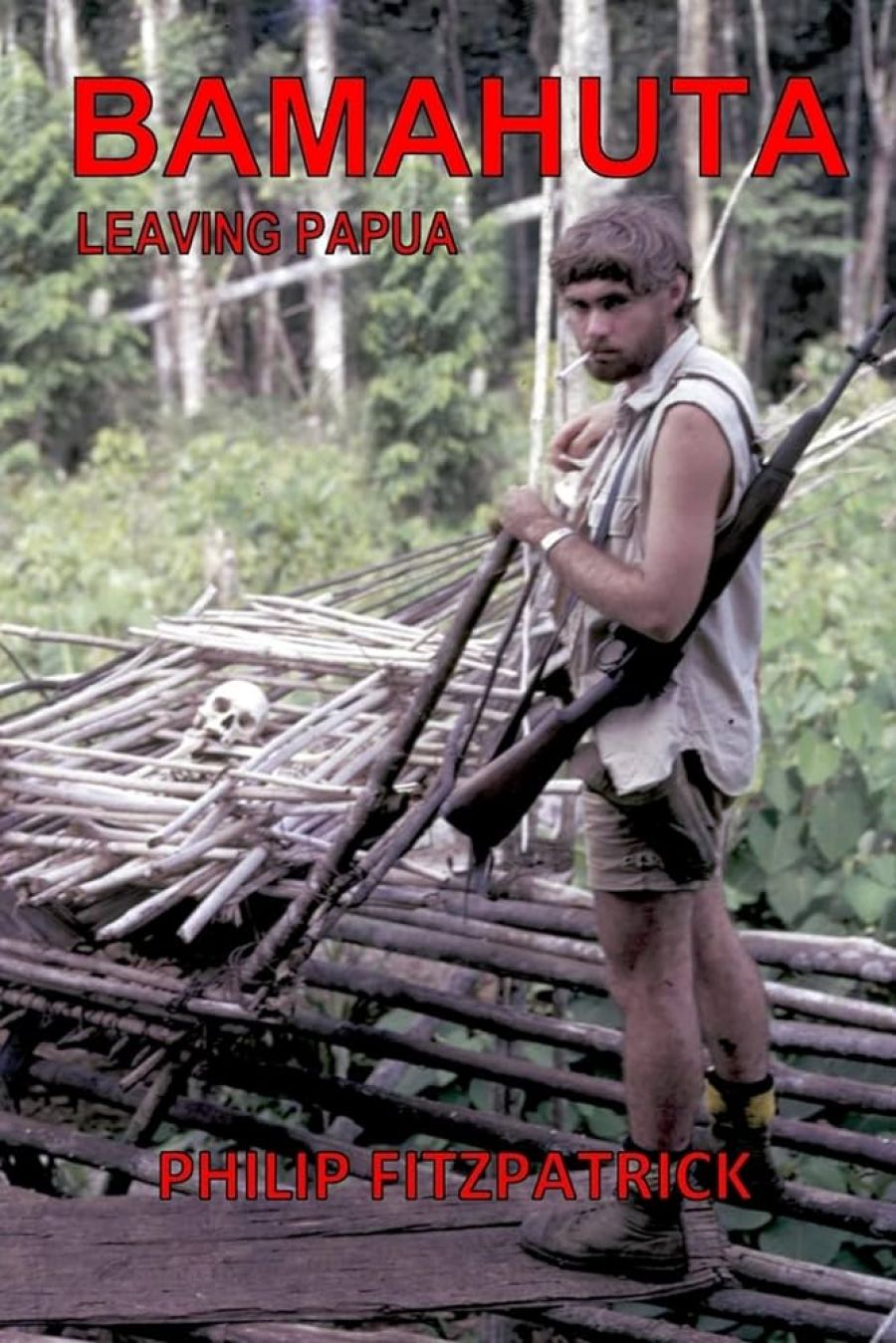

- Book 1 Title: Bamahuta

- Book 1 Subtitle: Leaving Papua

- Book 1 Biblio: Pandanus, $29.95pb, 313 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

The result today is a run-down country, a ramshackle state, a law-and-order crisis, Highlands tribal wars with real guns, drugs and grog, endemic corruption, high mortality rates, an HIV/AIDS pandemic, low (and decreasing) literacy rates and a great deal of human suffering. After some thirty years of independence, propped up by more than A$15 billion in Australian aid, PNG is not something of which Australia can be all that proud.

But it’s not all ignoble and clumsy. Some Australians who went to PNG made profound contributions. Some of these were kiaps: patrol officers toiling in extremely remote areas, bringing basic medicine, trying to nurture the well-being of villagers, sometimes building schools and aid posts, settling (or arbitrating) disputes, taking regular censuses and generally helping people as best they could. These interesting daredevils, mostly with only a secondary education behind them, could be extraordinary autodidacts who learned local languages and customs, and developed real insights into the lives of ‘their’ peoples. A few even studied for university degrees by correspondence, by the light of tilley lamps after a day of exhausting patrolling. Theirs was no cushy job. They had to rough it, out in the bush, cut off from outside contact for weeks at a time, utterly alone. A few went mad from the bottle or loneliness. A few ‘went native’, marrying or simply fornicating with a local meri (or meris), producing some exquisite genetic blending in their offspring. Not all of them were successful, and some were bloody-minded bullies. But a few were sensitively intelligent, a fascinating mixture of bluff Australian masculinism and sympathetic openness to bewilderingly diverse and different human beings.

Philip Fitzpatrick was clearly of the latter type. His blokey, no-nonsense style of writing makes for a very good read. He belongs to what we can usefully refer to as the ‘digger tradition’ of Australian writing. He vividly describes and wisely analyses experiences of harsh contact with dark worlds about as culturally distant as they could be from his native Australia. In addition, his book is a marvellous documentary account from a participant ‘on the ground’, of the fateful moment when Australia started to disengage from PNG; when it was about to decolonise gracelessly and hastily, adding to problems that had been accruing through eighty-odd years of desultory colonial administration. Like the majority of Papua New Guineans, Fitzpatrick watched the onrush of decolonisation balefully, sadly, not so much because he approved of colonialism per se but because he knew how utterly unready the people and their putative political leaders were for independence.

What makes Fitzpatrick’s account special is his refusal to conceal his dependence on his Papua New Guinean assistants:

I eased myself into the damp growth beside a bank on the track and wondered how I would ever get up again. Imbum disappeared and Kasari took his place. He deftly cut a leaf from a flat palm-like plant, folded it into a ‘V’ and pushed it into a soft part of the bank; soon a trickle of clear water flowed from the projecting leaf and I leaned over and gratefully drank.

What he conveys throughout the book is a warm respect and regard for Papua New Guineans, even as he wryly appreciates that, like him, they have their flaws. He is simultaneously frank and unsentimental, respectful and critical.

But as the book comes to its conclusion, just before independence in 1975, the problems that now bedevil PNG were beginning to emerge from the woodwork. Big-head local politicians, massively overestimating their capacities to govern the country, were starting to assert themselves. ‘Rascals’ (gangs of young thugs) were beginning systematically to burgle houses and to threaten people on the streets. The author’s house is broken into, but eventually the culprits are caught and sentenced. A few of his personal belongings are recovered – his passport and some other documents. The policeman returning the documents shuffles back into the courtroom. Fitzpatrick notes: ‘He was wearing a pair of my shoes.’ Very PNG.

This is an excellent book, readable, accurate and warmly human. It tells us much about how Papua New Guinea was governed under the Australians; and – artlessly, inadvertently – it tells us even more about one particularly interesting and admirable Australian, the author.

Comments powered by CComment