- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: More than the bare facts

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

There has been no escaping Graeme Blundell lately. There was Catharine Lumby’s astute reappraisal of his image-making Alvin Purple for the Currency Australian Classics series; and, as I write, the advertisements for the new local documentary Not Quite Hollywood feature a bare-chested Blundell in a pair of unforgivable 1970s flares. Now, here is his own account of how he got to be that way – and a good deal more.

Blundell was branded for years by the Alvin persona, that of the improbable sex symbol, irresistibly attractive to women who are turned on by this short, faintly nerdish suburban lad with a curious magnetism invisible to the naked eye. And naked, of course, was the key word. There is a good more to Blundell than the Alvin image, but let’s get it out of the way first.

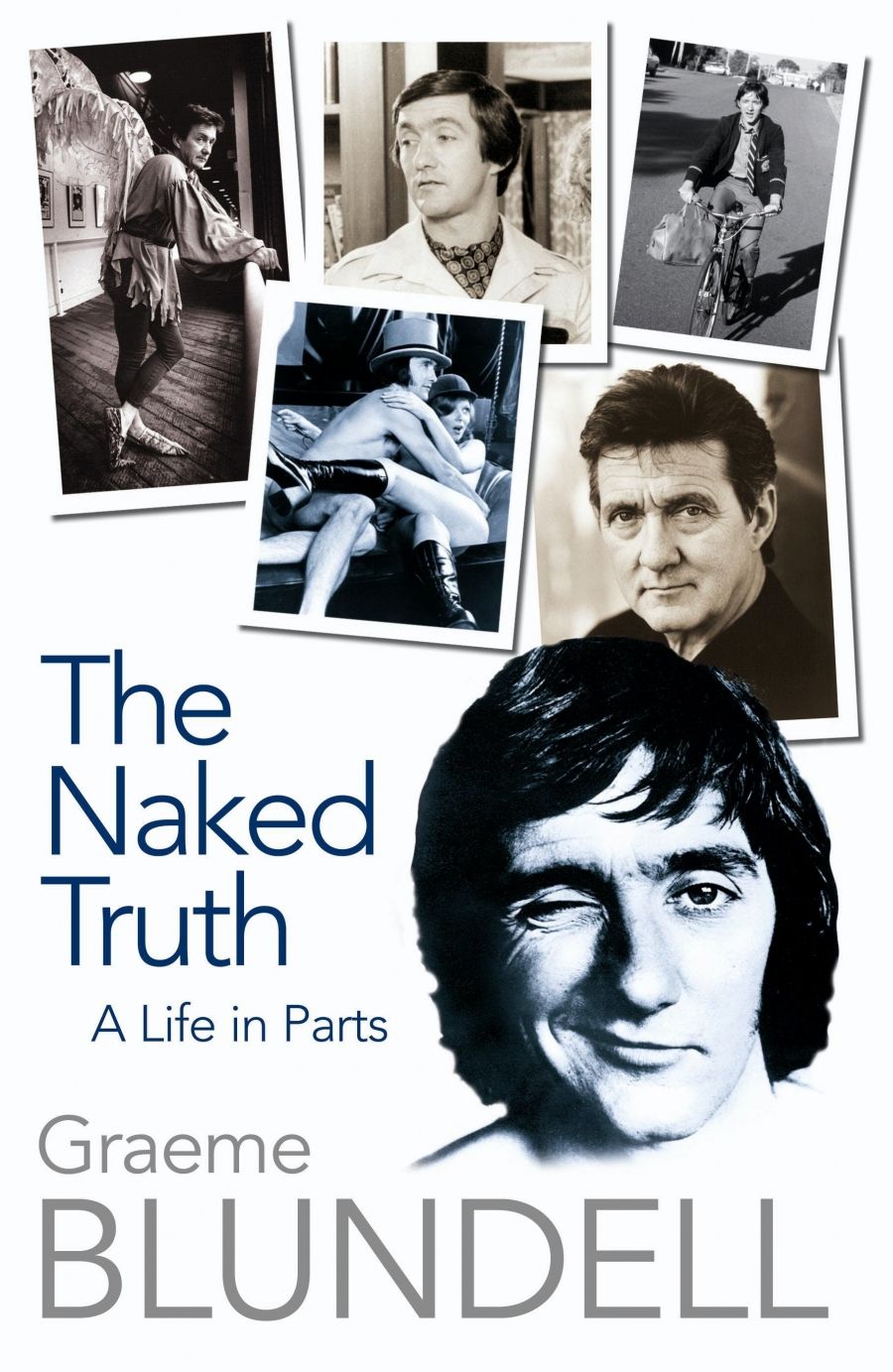

- Book 1 Title: The Naked Truth

- Book 1 Subtitle: A life in parts

- Book 1 Biblio: Hachette Livre, $35 pb, 312 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Blundell was branded for years by the Alvin persona, that of the improbable sex symbol, irresistibly attractive to women who are turned on by this short, faintly nerdish suburban lad with a curious magnetism invisible to the naked eye. And naked, of course, was the key word. There is a good more to Blundell than the Alvin image, but let’s get it out of the way first.

So what did Alvin Purple (1973) have going for it? Its director, Tim Burstall, who had made a success with his previous film Stork (1971), aimed Alvin with unpretentious accuracy at the Australian box offices. This was the time when the ‘R’ certificate of censorship, introduced in the early 1970s, was allowing a much more relaxed attitude to nudity and sex on screen, and Alvin certainly took advantage of this. However, as Lumby and Blundell both make clear, there is more to it than the mindless, leering ockerism it was once thought to purvey. Blundell describes its tone as a canny mix of Billy Liar (1963) and The Decameron (1971). Alvin Purple received a predictable mauling from high-minded critics, but these latter proved no deterrent to large audiences, which made it the most successful Australian film to that time. It made Blundell an instantly recognisable figure, accosted in public places and promoted as Australia’s first streaker. It inevitably gave rise to a sequel, and there was even a television series featuring the hapless Alvin. Blundell is wry and self-deprecating in chronicling the film’s runaway success, and he is honest in recalling its impact on his first marriage to actress Kerry Dwyer, a committed feminist. Dwyer should perhaps have noted that the women in the film were not passive sex objects.

To backtrack: The Naked Truth opens with an evocative account of growing up in Reservoir, then very much an outer Melbourne suburb. Blundell offers a vivid sense of the frontier-like ambience that recalls Steven Carroll’s memorable imaging of outer suburbia in The Time It Has Taken (2007). These early chapters are full of the precisely chosen detail that imbues place and people with vivid reality. Perhaps this is the result of what he identifies in his early self as ‘the reader’s feral watchfulness’. Consequently, there are sharply individuated studies of his parents – the outgoing, outspoken mother and the taciturn, war-damaged father who dies too soon – and of Pop, his Sorrento-based grandfather, severe at home and a charmer in the pub. In fact, one of the book’s major strengths is the way in which it so persistently endows its supporting cast with the breath of life.

‘Inertly happy’ during his schooldays at Coburg High School, Blundell knew he wanted to break free from ‘the smooth safe ways’ of quotidian Reservoir, nurturing vague Chandleresque fantasies of himself ‘confronting the darkness in the human soul while rolling [his] own cigarettes’. As a forerunner to his career, he entered the theatre as an usher at the Russell Street and Union Theatres, the bug first biting when he saw Reg Livermore and Zoe Caldwell at the Union in Patrick White’s The Season at Sarsaparilla, distinguishing between the way she ‘projected’ while Livermore ‘brought everything to him’. Blundell’s comments on performers are worth noting for their discriminating perceptions.

Following a more than respectable matriculation result, he entered the University of Melbourne, some of whose staff he nails in apt phrases, recalling historian Inga Clendinnen’s ‘inexorable sad smile and sharp charm’, and Ian Maxwell ‘wiping his tears with a large handkerchief’ as he recited slabs of Paradise Lost. This was a time of passionate interest in film, with names like Godard, Resnais and Antonioni bandied round the student population; and Blundell responded enthusiastically to this. He also fell, somewhat unexpectedly he says, into student theatre, making his début in a production of Ubu Roi. He enjoyed being introduced as ‘Blundell the actor’ and in those heady days of the 1960s he was not long in falling into his first love affair as well as into the lure of the performer’s life.

Blundell acted at the Russell Street Theatre during its legendary mid-1960s period (and is perhaps less than fair in his assessment of John Sumner’s achievement, overstressing its conventionality), but what really turned him on was the sense of a passionately alternative theatre. This he would find in Carlton, where a new radicalism was afoot under the auspices of Betty and Tim Burstall and La Mama, ‘a theatre where you could touch the actors’. This sense of radicalism was not confined to the theatre, but that is where it most made itself felt in Blundell’s life. This was a time of loosening community views of what was acceptable in matters of language and sexuality; censorship was under attack; there was a strongly vocal questioning of Australia’s participation in the Vietnam War; traditional theatrical verities were being challenged. For Blundell, as for many others, these were exciting times, and he got himself arrested for uttering the words ‘fucking boong’ in Alexander Buzo’s play Norm and Ahmed. The judge fined him $10 for this offence against ‘contemporary standards of decency’. The book evokes this seething period with perspicacity and perspective.

If Carlton theatre life was a form of extended family, the domestic scene he shared with Kerry Dwyer was often made tense by the conflicting demands of the theatre and by her strong commitment to the burgeoning women’s movement. The Australian Performing Group (APG), a renamed and in some respects revitalised version of La Mama, consumed a lot of Blundell’s energies, but left enough for him to star as a surprised innocent at large in John B. Murray’s film The Naked Bunyip (1970), a comic but serious look at censorship in Australia, especially in regard to sexual matters. This was Blundell’s first taste of becoming public property, with the feeling that ‘everyone in the country seemed to own bits of me’. The persona of shy guy caught up in a whirling sex revolution was born here, and honed in Alvin.

What is refreshing about Blundell’s memoir is the way in which the individual and the social are meshed, and the ways in which the professional interferes with the personal. The book is free of both egotism and solipsism, so that it stands not just as a record of a life with more than its share of achievements but also as a chronicle of seismic changes in society. As to how he deals with the major relationships of his life, there is a skilfully maintained balance between honesty and decency. In recounting his two failed marriages, he doesn’t let himself off lightly, and those wives aren’t summarily dismissed as earlier partners sometimes are in theatrical memoirs.

As well as being very readable, the book can also surprise with its felicitous phrasing: Edna Everage ‘rolled the words across her palate like forkfuls of poisoned pavlova’; or Bruce Spence as Stork had ‘a face like a suicidal greyhound’. If you were too young to be there at the time and want to know what all the fuss was about in the 1960s and 1970s, The Naked Truth will fill you in.

Comments powered by CComment