- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Speaking out

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Michele Gierck’s account of her years spent working as a human rights advocate in El Salvador raises the problem of how to understand other people’s lives. Early in 700 Days in El Salvador, she distinguishes between the two Spanish infinitives for the verb ‘to know’. Saber means to gain an understanding intellectually, through books or art, through a representation. Conocer is to understand by experiencing something directly, to live through it or to witness it oneself. Gierck’s passionate work on behalf of the Salvadorean peasants, or campesinos, is testament to her conviction that to conocer is truly to know. She attributes an inviolable sanctity to the stories of those on the ground, who witnessed the misery and fear in El Salvador during the decade of civil war and its equally troubled aftermath.

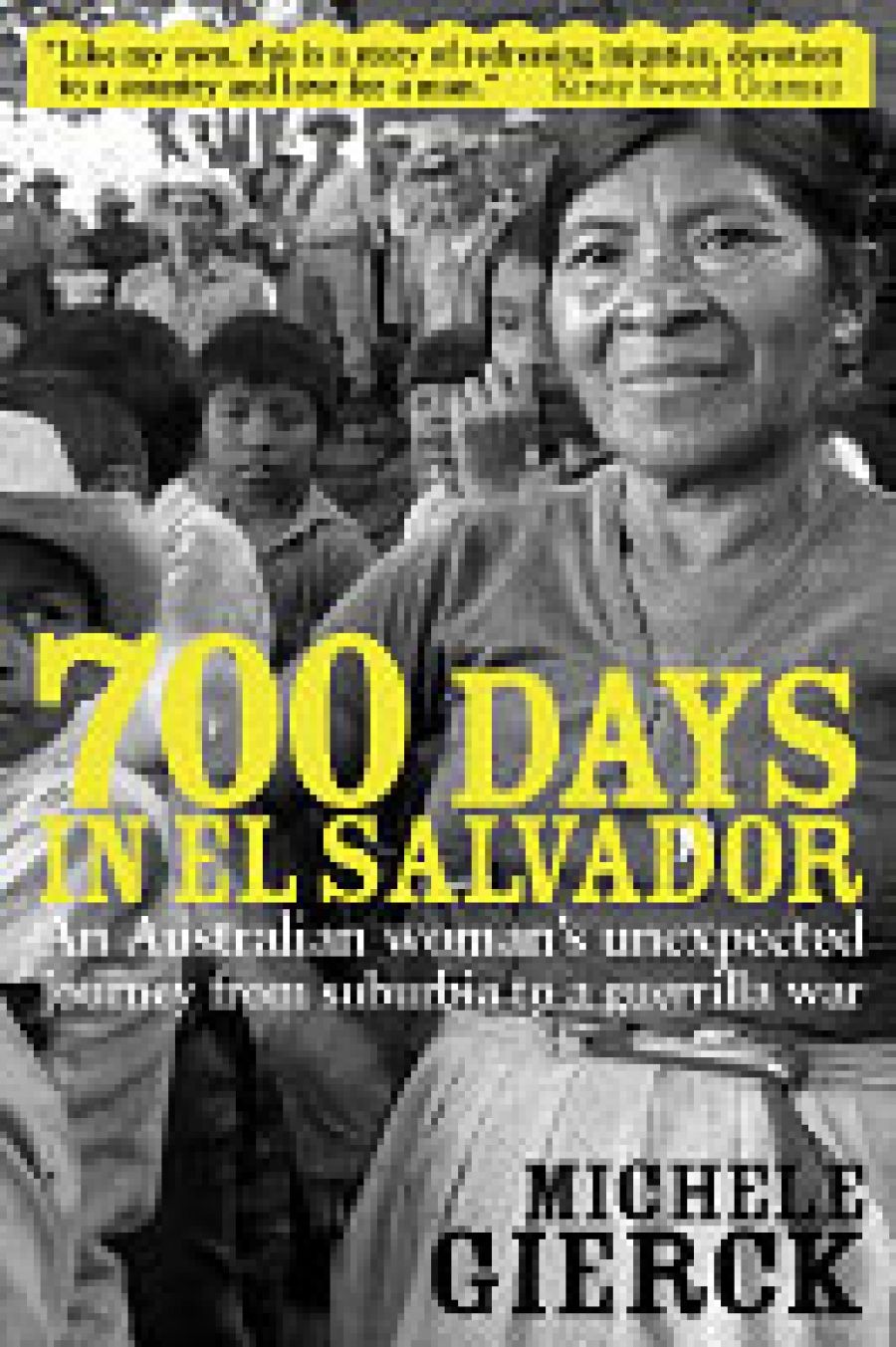

- Book 1 Title: 700 Days in El Salvador

- Book 1 Biblio: Coretext, $22.95 pb, 213 pp

The personal story behind 700 Days in El Salvador is compelling. When Gierck met José, a political refugee, in a Melbourne bar in 1989, her fascination with his stories of repression and political struggle in his native El Salvador led her to collaborate with him in raising awareness about the plight of his people. Together they translated scores of firsthand accounts of torture, murder and the disappearance of civilians at the hands of the Salvadorean military. Their affiliation with the San Salvador-based human rights organisation La Oficina presented several opportunities for the pair to travel to El Salvador and Nicaragua, where they participated in international forums and helped distribute information to community groups and refugee camps. Gierck’s passion and energy are evident in her determination to act rather than just offer sympathetic words. She is inspired by José’s commitment to his people, and is driven by a sense of personal responsibility to ‘speak out’.

700 Days in El Salvador is structured like a journal. Its short chapters are headed with places and dates, although they are not strictly linear, sometimes jumping forwards and backwards in time. This suits Gierck’s anecdotal aesthetic. She writes in a direct way about her experience of living in dangerous urban neighbourhoods and of her travels into remote rural communities. Keen to meet the people she feels so close to through her translations of their stories, she is a conscientious guide through both the human and geographical terrain, absorbing all the detail and colour of her new environment. Her warm observations of domestic life amid the social dislocation and tension reveal a people who are stoic and hopeful, despite entrenched poverty and constant intimidation by a cruel and unaccountable military state.

Gierck’s recurrent use of the Spanish phrase, el pueblo, takes on an almost mantra-like quality, reflecting her deep respect for those she meets as she works and travels. As a lapsed Catholic, she is conversant in the symbolic language of the campesinos and is clearly affected by the strong faith of el pueblo. She is drawn to frequent reflections upon the spiritual aspects of suffering and social justice.

However, despite Gierck’s sympathy, 700 Days in El Salvador does not have the impact it should. The references to el pueblo, and her solidarity with them, may go some way to explaining its ultimate lack of focus. She rightly recognises that it is important to gain a cultural understanding of the whole, of the group, especially after years of civil conflict. The solace and political power that can be gained through this solidarity is undeniable. But a better writer would define this in a more sophisticated way, using his or her status as an outsider among that group to imbue individual portraits with more dramatic purpose. Despite the disturbingly common tales of torture and murder, there is a real lack of analysis and insight. Everyone Gierck meets is either a good person struggling against oppression or an evil army swine.

There are many private reasons for writing a journal. When making the leap into publication, however, the challenge is to translate familiar accounts of direct experience into a living text which fleshes out the ideas, amplifies or tones down particular observations, dramatises particular events to emphasise their importance to the reader. It requires a degree of technical skill. Other accounts of Australian women’s experiences in Central America have been published in recent years. Cate Kennedy’s Sing, and Don’t Cry (2005) and Gabrielle Carey’s So Many Selves (2006) offer personal perspectives on daily life in rural Mexico. Both women are excellent writers who reflect with wit and intelligence upon their observations and their inevitable cultural assumptions. They depict a dignified people, while managing to avoid the flattening tone of reverence that blights Gierck’s prose. Gierck’s binary approach to ways of understanding is a literary construction which demands a literary method. Her simplistic faith in the purity of direct experience hinders an imaginative response to her work. The author has it all stitched up for us. She assumes the reader will accept her account as definitive, even as she expresses doubts about the possibility that anyone can really understand without firsthand knowledge. There is no doubt about Gierck’s good intentions – her strenuous advocacy and hard work are admirable – but in choosing to write about her time in El Salvador, she needed to craft her account in a way that would have better encouraged us to saber.

Comments powered by CComment