- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

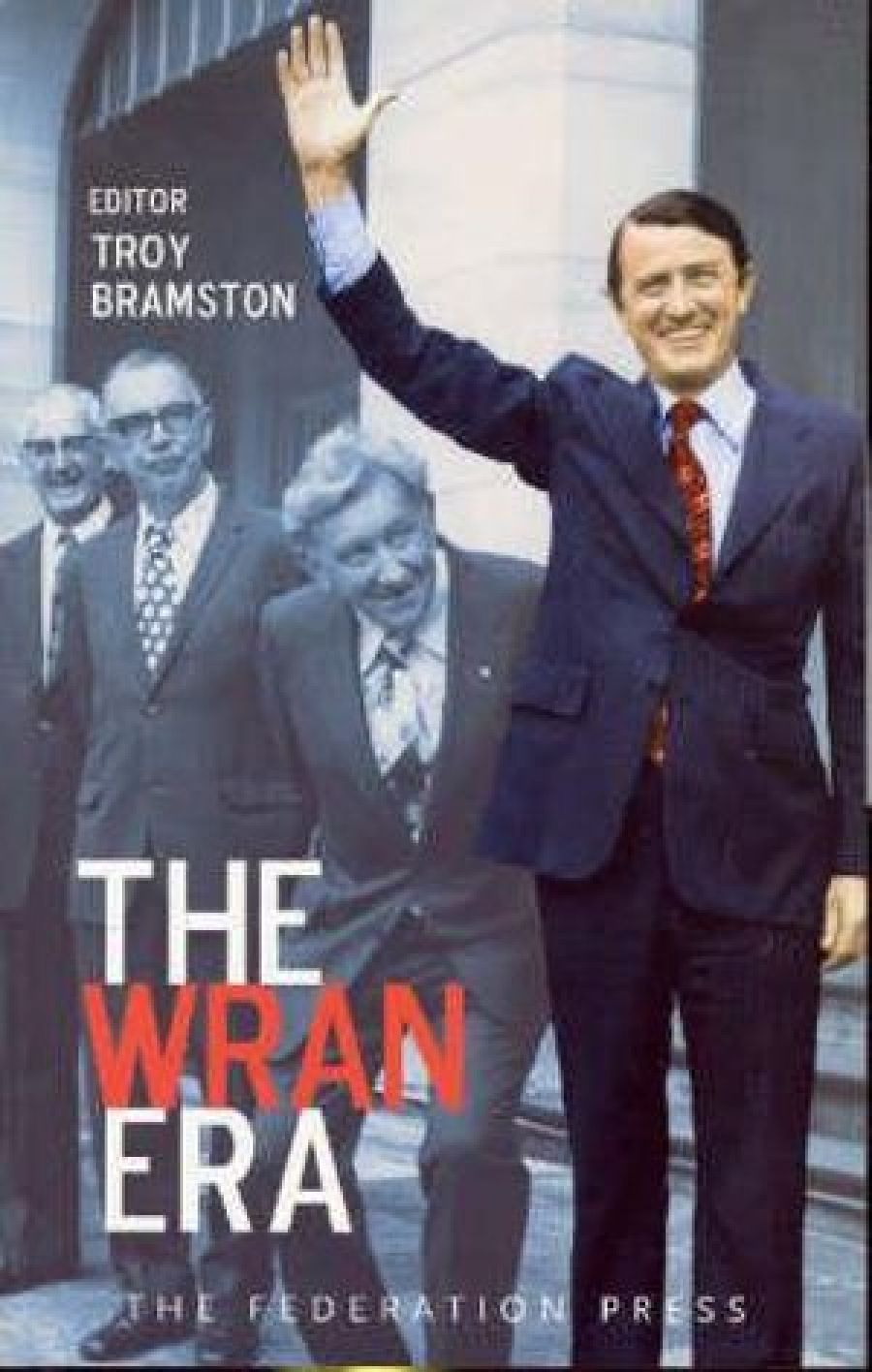

Neville Wran was nothing if not sartorial. He represented the new generation of politicians – dapper, immaculately tailored, effortlessly elegant – and stood out from his Labor colleagues in their crumpled suits and gaudy ties. His dress sense was not merely a matter of personal taste but also a political statement. He once appeared on the podium of a Labor party conference perspiring uncomfortably in the glare of the arc lights. A colleague leaned over and urged him to take off his jacket. Wran retorted, ‘What! And look like a Labor politician.’ It was classic Nev.

- Book 1 Title: The Wran Era

- Book 1 Biblio: Federation Press, $34.95 pb, 335 pp

Yet such qualities capture the special magic of Wran – his ability to rebrand Labor, to make Labor not look like Labor. His surprise victory in the state election of 1976 (straight after Malcolm Fraser had wiped out Gough Whitlam) and subsequent ‘Wranslides’ bear testimony to changing public perceptions. He transformed Labor into a modern ‘régime’, the key features of which are well known: they include presidential leadership bolstered by powerful factional lieutenants; stable government based on cautious reform; media management and a tight control of the political agenda; electoral dominance; damage control; and luck (see Chaples et al. 1985). Along with other state premiers of a similar vein, he laid the foundations of New Labor, which Bob Hawke and Paul Keating (and Tony Blair and Helen Clark) would inherit. The ‘Wran model’ also proved highly exportable to other state Labor leaders who fancied themselves as ‘also-Wrans’, including Wayne Goss, John Bannon, John Cain, Mike Rann, and Bob Carr.

But does it matter that Labor rules New South Wales, other than to the party faithful? It has long been said of New South Wales Labor governments that they ‘minded the shop’, acting as nightwatchman administrations and presiding over the state without doing much new or radical. If they were successful, then developments occurred due to longevity. This is the age-old backdrop against which the book is set: the notion that Wran was merely politically successful, a patient ‘do-nothing’ leader who, in his own words, ‘made New South Wales a slightly better place in which to live’ (reminiscent of ‘Piggy’ Muldoon’s famous exit line, that he left New Zealand no worse off than when he found it).

With many contributors talking from firsthand experience, how do these twenty-five authors fare in persuading us of the contrary? The Bramston formula for conceiving such retrospective ‘period book’ projects is becoming clear (his earlier The Hawke Government [2003] set the tone). He invites associates, colleagues, minders and senior executives who have worked with the leader to recall and reinterpret with the benefit of hindsight (thirty-one years having passed since Wran formed his first government). At least fifteen of the contributors worked with or for Wran and hold him in high esteem – it is hard to find a critical voice.

There are dangers in hagiography: self-serving justification, defensive revisionism, even nostalgia. Most authors directly confront the ‘did nothing’ label, countering it with Wran’s feats. Bramston is perhaps most guilty of gilding the lily, citing an odd list of achievements that includes the installation of night lights at the Sydney Cricket Ground to allow World Series Cricket to play day–night games. Against this, journalist Dennis Shanahan reminds us of Wran’s own admission that ‘[he] didn’t set out to achieve much, actually’ and regarded the ability to get a drink on Sunday as one of his greatest accomplishments.

Others try to give us a flavour for the times. David Hill talks about himself and his own career moves. Rod Cavalier was commissioned to describe the workings of cabinet, but instead gives us his views on factional manoeuvrings. Rod Tiffen describes the variously obsequious and poisonous relationships between politicians and the media, hovering between promotion and payback, while noting Wran’s own vindictiveness and preference for the ‘counter-attack’ strategy. In many chapters, there is more than a hint that the corruption scandals that marked Wran’s last four years were partly conservative and media conspiracies to bring down the great man.

The policy section of the book, containing twelve contributions by eminent practitioners, often degenerates into lists of problems and activities. Laurie Brereton talks about finding hospital ‘beds to the west’; John Black describes the breakneck road-building programmes that eventually exacerbated transport congestion in Sydney; Andrew Clark discusses the corrosive culture of corruption at senior and local levels, which Wran’s government presided over and largely ignored. Frank Walker tries to paint Wran as a big social reformer (comparing the number of bills passed by his government with those of Nick Greiner and Carr) who deliberately gave the impression he was underperforming in this area. Carmel Niland and Pat O’Shane both turn an optimistic eye to their topics, but lament the lack of substantive progress in women’s and indigenous policy areas, respectively.

Overall, the chapters of this book add some colour to our appreciation of the Wran era, but little to the understanding constructed by academics (the Chaples team) by Freudenberg’s party history (1991), or by the Steketee and Cockburn biography of Wran (1986). Perhaps the one thing that stands out from these recollections is the enormous behind-the-scenes role played by Wran’s deputy, Jack Ferguson, well known but not well recorded to date. My main disappointment with the collection was that few, if any, of the authors ever looked outside New South Wales to see what other states were doing at this time, especially Dunstan in South Australia. The result is that the assessment of The Wran Era remains insular and self-referenced.

Comments powered by CComment