- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The plans for this book were announced at the time of Ninian Stephen’s eightieth birthday, almost four years ago. Each of the ten contributors focuses on one of his public roles in the last thirty-five years – five of them in Australia, and five on the international stage. The last of the Australian positions, ambassador for the environment, is a bridge between the two. Kenneth Keith’s chapter finds another bridge: in Koowarta v Bjelke-Petersen (1982), on Stephen’s last day as a High Court judge, his judgment decisively transformed the issue of racial discrimination in Queensland by recognising its international potency.

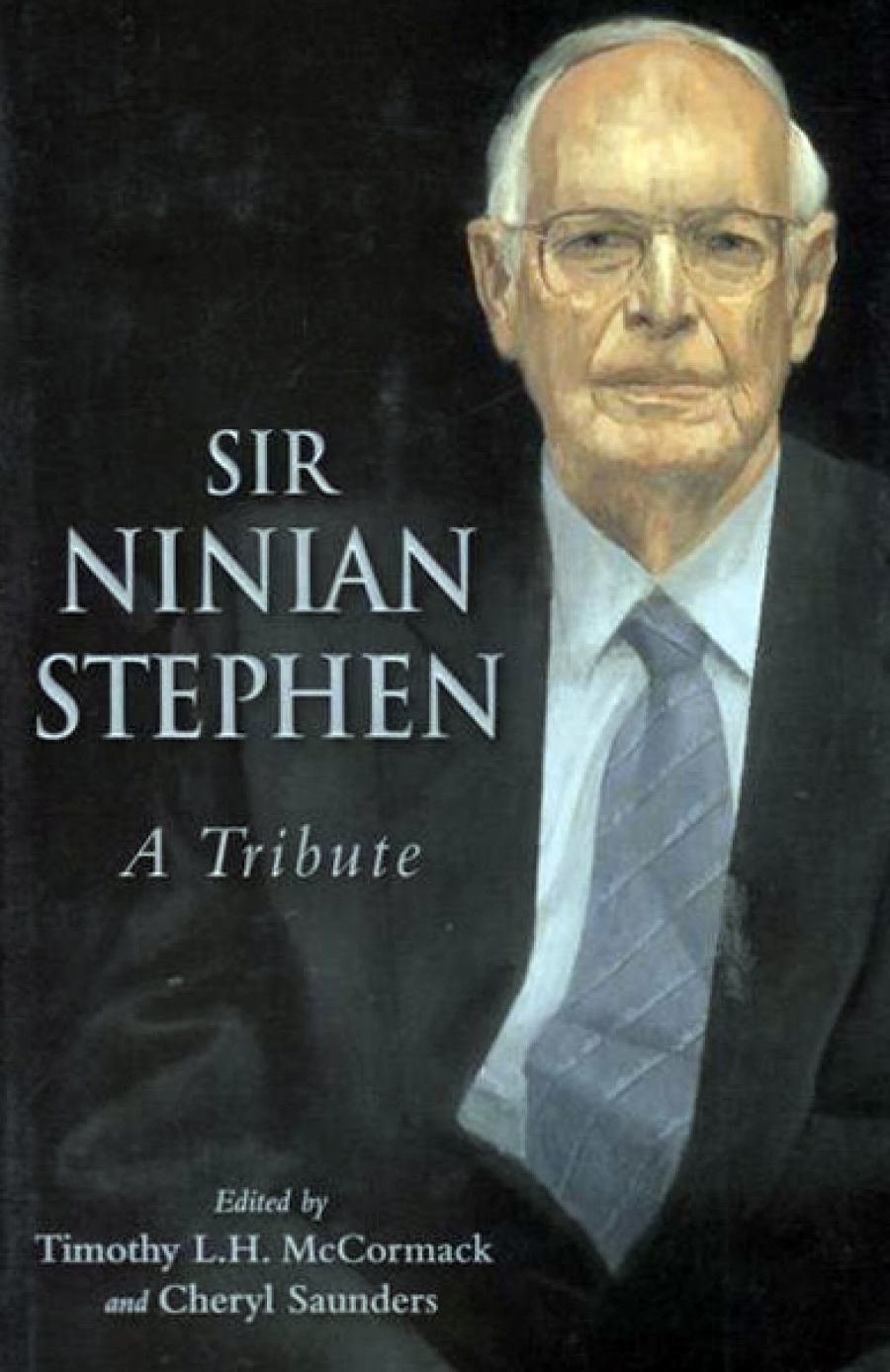

- Book 1 Title: Sir Ninian Stephen

- Book 1 Subtitle: A tribute

- Book 1 Biblio: Miegunyah Press, $65 hb, 294 pp

From 1972 to 1982, Stephen sat in 472 reported High Court cases (including twenty-two as a single judge). Anthony Mason’s chapter singles out twenty-five of these, partly to illustrate Stephen’s elegant prose and his contributions to legal doctrine, but also as a vehicle for theorising about the judicial process. When Stephen remarked that no one view of the Second Territory Senators Case (1977) was ‘inherently entitled to any preeminence’, so that phrases like ‘plainly wrong’ and ‘manifest error’ were ‘merely pejorative’, he meant it as a rebuke to the dogmatism of Garfield Barwick. But for Mason it illustrates the death of the declaratory theory of law. Similarly, he finds in Stephen’s judgment in the Caltex Oil Case (1976) a remarkable balancing of caution and candour in judicial attention to ‘policy’, and in White v Barron (1980) an even more explicit balancing with regard to judicial recognition of changing social values.

Geoffrey Lindell’s chapter on Stephen’s term as governor-general (1982–89) is primarily directed to academic debates on appropriate vice-regal functions in an independent democracy. He dips into Stephen’s vice-regal speeches, including a perception of Australian values as evincing ‘a cheerful cynicism; a refusal to be, or at least appear to be, reverential about what other nations regard as solemn and sacrosanct’. Otherwise, he explains that Stephen’s tenure was remarkable precisely for its lack of incident – no exercise of personal discretion; hence no controversy; hence no interesting stories. What, then, of the 1983 double dissolution, when Stephen insisted that Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser amplify his recommendation with a reasoned justification? Initially, Lindell explains that he has dealt with that incident elsewhere; finally, it emerges that he thinks Stephen was pushing the envelope too far (though not as far as William Deane).

In 1991 Stephen presided at the Constitutional Centenary Conference. Thereafter, he led the Constitutional Centenary Foundation until 1997 as chairman, and then until 2000 as patron. Cheryl Saunders’s chapter explores the Foundation’s interaction with politicians during the 1990s, but also reflects thoughtfully on the difficulties of constitutional reform in Australia, on the greater role the Foundation might have played in different circumstances, and on its contribution nevertheless (for example, through the National Schools Constitutional Convention) to public awareness of constitutional issues.

In 1998 Philip Ruddock, as minister for immigration, appointed Stephen to chair the Australian Citizenship Council. Kim Rubenstein’s chapter shows how the Council’s report in 2000, Australian Citizenship for a New Century, resulted two years later in legislative changes allowing the possibility of dual citizenship. She contrasts Stephen’s responsiveness here to changing concepts of nationality under pressure of globalisation, with his cautious legalistic adherence, for purposes of international criminal law, to traditional ideas of nationality. She also reviews his observations about citizenship in other contexts. She could perhaps have said more about his support for multiculturalism, and about the rather ambiguous relationship between the 2000 Report and the further legislative changes in 2005.

As Australia’s ambassador for the environment (1989–92), Sir Ninian contributed greatly to international environmental awareness, particularly through the campaign against Antarctic mining and his preparations for the Rio ‘Earth Summit’. He was equally active as an ambassador to Australia for the environment, speaking on such topics as ‘pollution in the Yarra River … women and the environment, migratory birds, and … the Landcare movement’. Along with much detailed insight into these developments, Doug Laing’s chapter explains their wider historical background, both in Australia and elsewhere. His account of the growth of scientific concern about chlorofluorocarbons, and later about climate change, is especially helpful.

Under the heading ‘International Peace Envoy’, Timothy McCormack lumps together four of Stephen’s assignments: in 1991 as one of the British Commonwealth’s Group of Distinguished Observers in South Africa; in 1992 as chairman of the Northern Ireland Peace Talks; in 1994 as a mediator between political parties in Bangladesh; and in 2001 as leader of a team to assess (for the International Labour Organisation) attempts to stamp out forced labour in Burma. In South Africa, the observers’ contribution was minimal; in the other initiatives, the immediate result was a failure. But in all these contexts, McCormack demonstrates Stephen’s remarkable skill at balancing diplomatic forbearance and modesty with imaginative and resourceful interventions. At least in Northern Ireland, Stephen’s work clearly made a real contribution to later more successful developments.

To be a member of the Permanent Court of Arbitration, as Sir Ninian has been since 1989, is not quite what it seems. The members (four from each participating country) form a panel from which parties to an international dispute may (but need not) choose arbitrators. In 1993 Stephen presided at the first general meeting of members in the Court’s history. Kenneth Keith’s chapter traces that history from the first initiative of Czar Nicholas II in 1898, to the growing popularity of international arbitration in recent decades. In practice, the members’ most significant role is to formulate their country’s nominations of candidates for election to the International Court of Justice. Keith carefully reviews what is known about how this process works, with reference to Australia and the actual or possible nominations over the years of Percy Spender, Kenneth Bailey and Gough Whitlam.

Stephen himself sat judicially in the International Court of Justice as an ad hoc Australian judge when Portugal sued Australia in 1991 as a legal stratagem to obtain a ruling on Indonesia’s role in East Timor. In 1995 the Court rejected the stratagem, holding that it could not adjudicate on Indonesia without Indonesia’s consent. Stephen joined in the majority judgment. Hilary Charlesworth fleshes out these facts with a fuller history of the East Timor dispute, and a thoughtful review of arguments for and against the use of ad hoc judges from litigant countries.

Stephen’s role in the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (1993–97) was far more demanding. His fellow judge Antonio Cassese gives a detailed account of Stephen’s contributions. In particular, he explores the case of Duško Tadiæ, where the problems of nationality in a dismembered nation led Stephen to join in a 2:1 majority effectively denying the applicability of the Geneva Conventions; and the case of Drazen Erdemoviæ, where Stephen joined Cassese in dissent from the holding that Erdemoviæ, who reluctantly joined in the slaughter of Bosnians to avoid being shot himself, could not rely on a defence of duress. The final chapter deals with Sir Ninian’s role in 1998–99 as Chair of the United Nations Group of Experts seeking some effective means of accountability in Cambodia for the Khmer Rouge atrocities twenty years earlier. Steven Ratner, himself a member of the group, concedes that its recommendations were doomed to failure by insisting on a trial outside Cambodia by a fully international tribunal, but continues to believe that recent moves towards a mixed tribunal of Cambodian and UN-appointed judges will also be ineffective. This book is a mixed bag, and the results are uneven. Some contributors have too much to write about, others not enough. In some contexts, Stephen’s contribution was extensive; in some, it was relatively slight. In some, it was controversial; in others, it depended precisely on a lack of controversy. Only Stephen’s personal engagement links all the issues involved. Michael Kirby’s exuberant foreword offers a rewarding overview, but a chronological table would have helped.

all the contributors agree on Sir Ninian’s personal ‘urbanity and charm’, and his ‘elegance of literary style’. (I take these phrases from Mason, who also recalls ‘the most mellifluous voice in the Australian legal world’.) All of them illustrate Stephen’s tendency to cautious legal conservatism, yet also his far-sighted capacity both for sensitive recognition of social change and creative responses to it. Rubenstein suggests that perhaps the conservatism was dominant in judicial contexts, the creativity in diplomatic contexts. Yet the real enigma is that Stephen displayed both these qualities in all his activities – though Kirby rightly suggests that his High Court judgments increasingly evolved beyond their ‘somewhat conservative’ beginnings.

James Thomson has lamented our curious reluctance to write biographies of Australian judges. Clearly, Stephen will be a remarkable subject for such a biography; and this book will provide useful material.

Comments powered by CComment