- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

It is now thirty years since James McAuley died, and more has been written about him in that time than about any other Australian poet. Poets are not usually of great biographical importance unless they are also caught up in historical and political events, or are a kind of phenomenon like Byron or Rimbaud. McAuley was not a man of action, but he was associated with a number of events which were significant in Australian development and culture; and a large, some would say inordinate, part of his life and energy went into politics and polemics. He became something of a public figure, and, as he himself recognised, the lives of such figures quickly become public property. Any book about him is bound to be of interest.

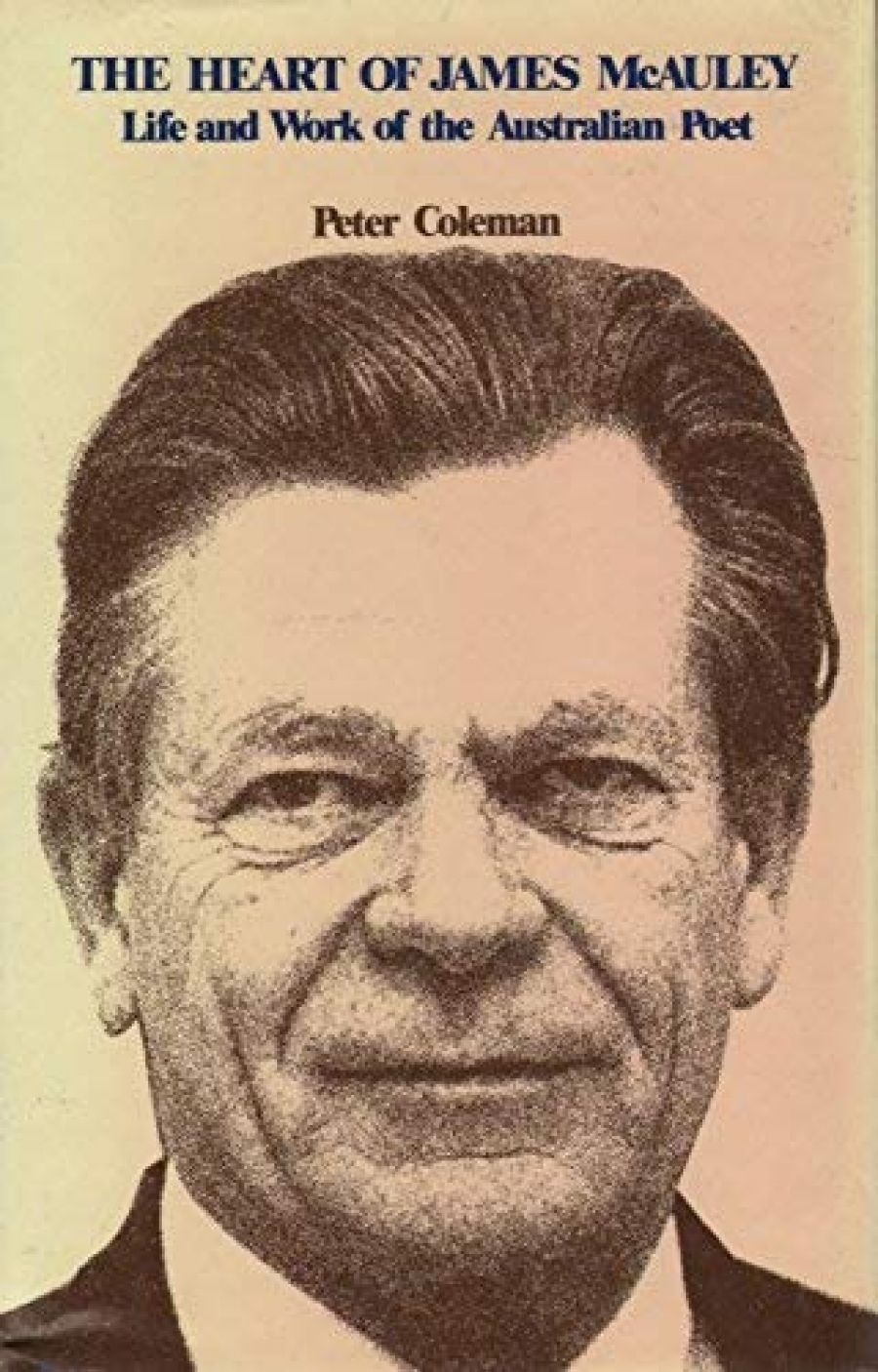

- Book 1 Title: The Heart of James McAuley

- Book 1 Biblio: Connor Court Publishing, $29.95 pb, 133 pp

McAuley now has two main claims to fame: he was one of the perpetrators of the most notorious literary hoax in Australian history – ‘Ern Malley’ – and he was a poet in his own right. But the brilliant anarchist student from Sydney University in the 1930s was also involved for a time with Pacific administration and the development of postwar New Guinea. In 1952, as the Cold War was taking hold, he became a Roman Catholic and a committed anti-communist. In 1956 he was appointed the founding editor of Quadrant, the Australian Committee for Cultural Freedom journal which was opposed to the totalitarian régimes and police states of the time, and he became a vocal presence in local debates and discussions. Given his public profile, it was inevitable that he should have opponents, even enemies. Some loathed his political and literary conservatism, others his particular brand of Catholicism, but he was widely admired for his integrity, and personally liked by many who shared neither his political nor his religious views. He was a complex personality, combining more disparate elements than most.

McAuley was a figure of controversy, often involved in controversies, and the problem for those who write about him is how to get the balance right between the public intellectual and the private poet. Some recent writers, having heard that McAuley was a bit of a devil in his youth, have tried to expose his demons, but there have been few attempts to see his life and work as a whole. If we are still interested in McAuley, it is due more to his poetry than to his role in a number of public controversies. Young readers in particular are now drawn to McAuley’s uncertainties, his vulnerabilities, his melancholy and insecurity, to that personal element he was developing in his verse, rather than to the slogans and convictions of the Cold War warrior. The poetry is leading a life of its own. ‘A verse may find him who a sermon flies.’

The Ern Malley hoax is now a growth industry. Sixty years ago, nobody could have predicted how the case would develop, nobody could have foreseen its afterlife. Harold Stewart, the other half of Ern Malley, claimed that one day ‘it will be irrefutably proved that James McAuley and Harold Stewart were really figments of the imagination of the real-life Ern Malley and in fact never existed’. The hoax has inspired novelists, poets, painters, theoreticians, and its lines are used by other writers as titles for their books; but those who write about it rarely know how to relate it to McAuley’s and Stewart’s own lives and work. Literary criticism and judgment depend on fine distinctions and delicate discriminations, and the simple fact is that the ‘The Darkening Ecliptic’ contains one of McAuley’s finest poems, as well as cross-references to some of his early lyrics. An annotated line-by-line edition would make some of these connections clear. The Ern Malley poems are brilliant satirical parodies and concoctions, extraordinarily funny in places, learned exercises in collage, trickery and entrapment.

Peter Coleman’s book, now reissued with a feisty preface by R.J. Stove, first appeared in 1980, a few years after McAuley died. A key phrase in McAuley’s early poetry is ‘world unsimplified’, and Coleman’s book is a quiet challenge to those who want to simplify McAuley and put him into some predetermined mould. It is to Coleman’s credit that he quotes the poetry so abundantly and leaves it to speak for itself. A short survey of McAuley’s intellectual and literary background, all the more valuable for being written by a sympathetic colleague, it is not as theoretically sophisticated as Lyn McCredden’s James McAuley (1992), but it aims at a wider, much less specialised audience, and it covers McAuley’s essays and critical works, as well as including extracts from some of his exceptional letters to Dorothy Green and A.D. Hope. Anyone who wants to know why McAuley mattered to so many people, what he was really like, and something of his life and times, should start here.

Coleman is one of the few to stress the importance of German poetry for McAuley’s development. His translations of Georg Trakl and Albrecht Haushofer are well known internationally, his version of Hugo von Hofmannsthal’s Manche freilich is the best I have read, and his fine rendering of Rilke’s Herbsttag is often anthologised. Quotations from Stefan George and Novalis are incorporated into some of McAuley’s own poems, and Coleman identifies these clearly, though without exploring their usage.

Less noted is McAuley’s admiration for A.E. Housman, whose influence may be discerned in some of his lyrics. In the 1930s McAuley quoted the following poem in an important letter, but did not include it in his anthology Generations: Poetry from Chaucer to the Present Day (1969):

When the bells justle in the tower

The hollow night amid,

Then on my tongue the taste is sour

Of all I ever did.

It is a clue, I think, to aspects of his later work.

Comments powered by CComment