- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The United Nations’ eighth secretary-general, Ban Ki-Moon, has just taken over what has been called the world’s worst job. But it is one that attracts fierce, devious and polite competition. Why would anyone seek, for less than $400,000 a year, to be the chief administrative officer of a non-government that cannot govern, a non-corporation that cannot borrow or invest? The UN’s total budget is about the same as the New York City school system, and the secretary-general has to beg 192 national stakeholders for funds even to carry out what they instruct him to do. Who would want to be answerable, as well, to a fifteen-member board, five of whose members use their permanency to frustrate others and advance their own interests, rather than those of the organisation?

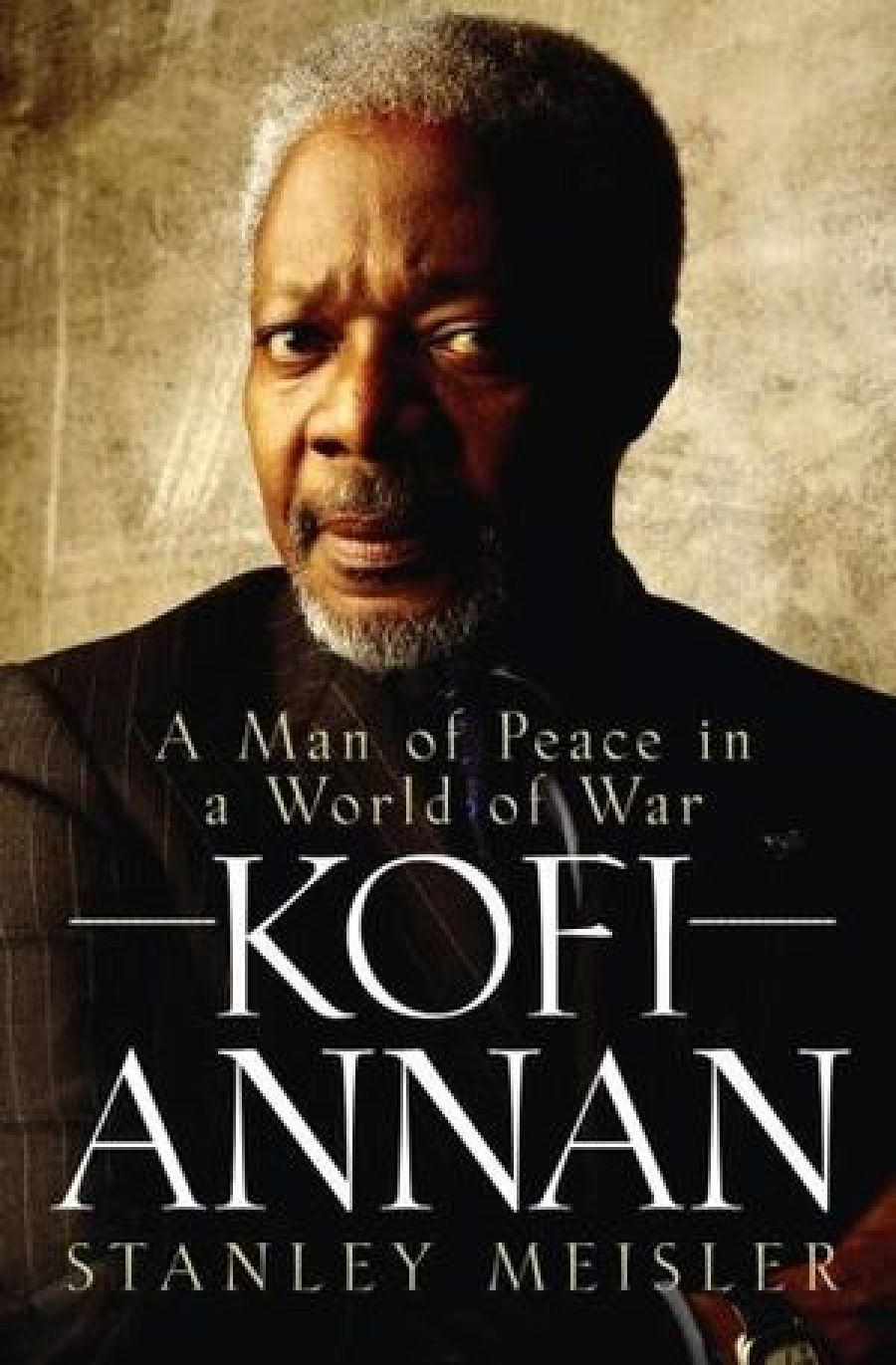

- Book 1 Title: Kofi Annan

- Book 1 Subtitle: A man of peace in a world of war

- Book 1 Biblio: Wiley, $44.95 hb, 372 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/5OqrD

Kofi Annan was unusual as a secretary-general in having neither expected nor sought the job. A Ghanaian who was educated in the United Kingdom and the United States, he worked his way up through the UN Secretariat. He was chosen in 1996 when a black African was needed to replace the Egyptian Boutros Boutros-Ghali, who had fallen out with the United States. Stanley Meisler, in this biography, depicts Annan as personally unusual too: modest but dignified, diplomatic but determined, non-intellectual but intelligent, pragmatic but highly principled. Droppin’ his gs in English, he was a man of the people; being a French speaker and married to a Swede, he was cosmopolitan; and he had a reputation for steadiness. Under Annan, the kingmakers were sure, the UN would not cause trouble.

He inherited trouble: peacekeeping in Somalia, Rwanda and Bosnia; AIDS; the Palestinian question; and the perennial UN problems of poverty, refugees and human rights. But as under-secretary for peacekeeping between 1992 and 1994, he had set up nineteen new operations. For their progress in particular, Annan and the UN won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2001. The media loved him.

Then came Iraq, and trouble. Annan fell from American grace for saying what was true: that invading Iraq unilaterally was not ‘in conformity with the Charter’; in other words, illegal. From then on, they punished him. In his Nobel speech, the full text of which is appended by Meisler, Annan said: ‘When states undermine the rule of law and violate the rights of their individual citizens, they become a menace not only to their own people, but also to their neighbours, and indeed the world.’ Diplomatically, he left it to his listeners to work out which states he had in mind.

Colin Powell misled the Security Council in February 2003 about Iraq’s weapons. George W. Bush, Tony Blair, and John Howard preferred their doctored intelligence to the findings of the new weapons inspector Hans Blix. They defied and insulted the Security Council, the UN and the secretary-general. Then, after bombing Iraq for three years and plunging it into civil war, they expected the UN – more than twenty of whose staff in Baghdad were killed in August 2003 – to come back and rebuild it.

Future historians looking at this era, says Meisler, will see and write about little else but Iraq. He gives Richard Butler, chief weapons inspector before Blix, low marks. The Australian’s views ‘were similar to those of the Bush White House’. Butler refused to discuss with Annan the weapons he was adamant Saddam Hussein had. ‘Despite a lack of evidence, he never had doubts,’ Meisler writes. Butler was ‘an aggressive and undiplomatic diplomat’, whom Annan saw as a bull who rampaged through Iraq ‘without any regard for Iraqi feelings and then exaggerated what he found’.

Apart from his uncomplimentary references to Butler, and three pages touching on Australia’s role in East Timor, that is it from Meisler about Australia. His subject, of course, is Annan. Gareth Evans’s work on changes to the Security Council and recommendations for humanitarian intervention are not mentioned. Nor are Australia’s contribution in Cambodia, the East Asian economic crisis or the Indian Ocean tsunami.

There are some advantages in being small and easily disregarded. Meisler makes no mention of Australia’s participation in Afghanistan or Iraq, nor of our decade-long recalcitrance on the Kyoto protocol, human rights and development goals, and our uncritical support of American policy on most things, including Israel. More surprising is his omission of Australia’s sins under the Oil for Food programme. Governments were obliged to certify to the UN the contracts their nationals had with Saddam Hussein’s régime for buying oil and selling humanitarian supplies. Australia certified accounts from AWB for sales of wheat that were inflated by as much as $300 million, which was billed to the UN – the largest kickbacks paid for food.

Meisler presents Kofi Annan as more sinned against than sinning in Oil for Food, and as erring only in trusting people more than they deserved. He represents Kojo Annan – the son of Kofi’s first marriage – as an uncontrollable young man who misused his father’s influence without his knowledge, much like Mark Thatcher, perhaps. But Oil for Food was intended by the Republicans to punish the secretary-general for Iraq, and it did: Kofi Annan’s reputation was on the line, and he became so depressed that he had to be dissuaded from resigning.

The irony is that the amounts involved in Oil for Food shrank in comparison to Enron, or to the funds for which the Coalition Provisional Authority could not account after the Iraq invasion. As always, the secretary-general could only invite sovereign member states to supervise their own companies properly, and if they didn’t, he was powerless to punish them. That is why Howard, Alexander Downer and Mark Vaile sailed through the Cole inquiry last year, and then let AWB claim its bribes to Saddam Hussein as tax deductions.

Annan sometimes spoke of his ‘sacred duty’ to defend the Charter, and he used phrases of its inspiring language as epigraphs in his speeches. He knew, however, that the UN provides the world with two essential services for which, in spite of their disillusionment with it, member states keep paying. One is providing a spotlit stage on which the leader of every vote-wielding member state can declaim to the world once a year, and on which several Latin Americans and Middle Easterners have recently paraded to great effect. The other service is to be the world’s scapegoat, which member states can blame for their failures and whose successes they can claim as their own. The Internet on the UN reveals the global dichotomy. One set of messages is about UN days celebrated in many developing countries, mock General Assemblies held, elections supervised, projects realised, funds raised. Another set, mainly from the United States, is about the UN as an alien in Manhattan, the hated ‘chatterbox’, as neo-conservative Richard Perle called it when in 2003 he prematurely thanked God for its death. Saddam Hussein, Perle predicted, would go down, but not alone: he would take the UN down with him. An American source likened Kofi Annan to the devil incarnate; another author claimed that he headed a global conspiracy to overthrow the United States, and Ambassador John Bolton said there should be only one veto, held by the United States.

Stanley Meisler says that of all the secretaries-general only one is remembered as great. Lie and Thant were ineffectual, Waldheim was corrupt and concealed his Nazi past. Perez de Cuellar, it was said, wouldn’t make waves if he fell out of a boat; and it’s not yet clear whether Ban will make an impression on a soft cushion. But if Annan had been able to head off Iraq and its consequences, he could have got his reforms through, and he would have rivalled Dag Hammarskjöld. Or he too might have died in a mysterious plane crash.

Comments powered by CComment