- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Terrible longings

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

At the close of the twentieth century, in the tradition of countless Westerners before him, British travel writer Julian Evans travelled around the Pacific. At the Kwajalein atoll in the independent republic of the Marshall Islands, he found the resident US missile testing base to be efficient, clean and ‘tidy, quiet, ordinary: suburban trailer-park America at its best’. No Marshallese lived at Kwajalein, but 10,000 of them huddled on the small neighbouring island of Ebeye, whence they commuted to provide labour for the base. At Ebeye, nothing was ‘real nice’, as Evans described:

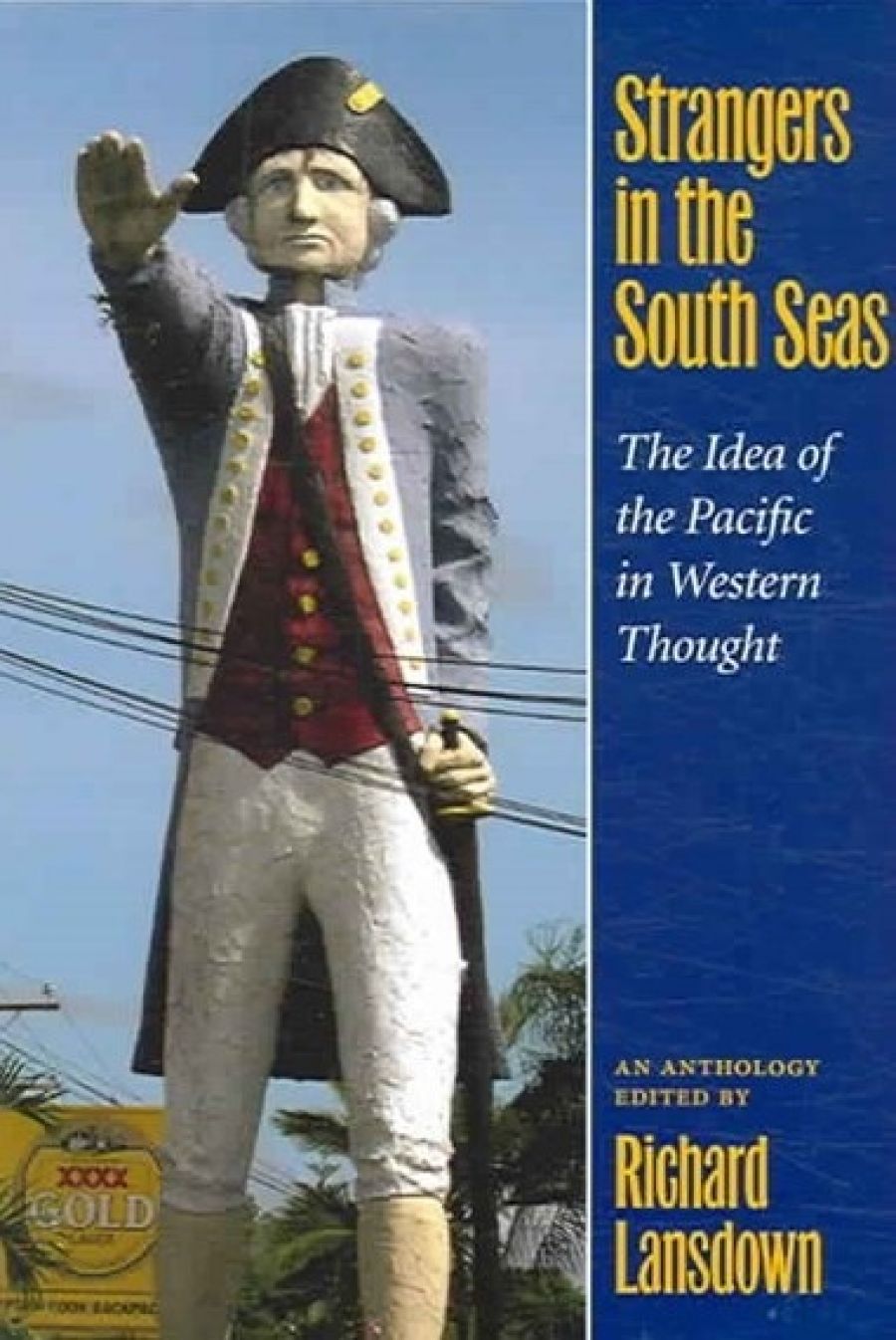

- Book 1 Title: Strangers in the South Seas

- Book 1 Subtitle: The idea of the Pacific in western thought

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Hawai'i Press, $58.95 pb, 447 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/vnrD2O

The shore: the density of garbage gave it the appearance of a clumsy land reclamation project. Everywhere there were oil-drums, old tricks, earth-movers, the carcasses of cars, freight containers, transmissions, tyres, split bags of house-hold waste, beer cans, disposable nappies. Among the bonanza of waste, the children crawled and played, grinning, their faces streaked with rust … I had stumbled upon another new Pacific myth, man-made like the thunderbolts the islanders watched overhead. Almost treeless, sanitationless, overrun by children under fourteen, it was no earthly island. It was the lost slum of Atlantis.

It is this mythological status of the Pacific – which, despite Evans’s contemporary disillusion, remains most powerfully etched on the Western imagination in the form of lush tropical islands inhabited by carefree peoples – that is the subject of Richard Lansdown’s comprehensive anthology. Lansdown has gathered a rich trove of writings to illustrate the ways in which the idea of the Pacific has been influential in the development of Western thought since Magellan crossed the Pacific Ocean in 1520. Since classical times, there had been conjecture that a great southern continent, surrounded by unknown seas, must exist as a means of balancing the northern hemisphere. But the West’s ‘discovery’ of the Pacific islands and Australia (with its eastern half rimmed by the Pacific Ocean) coincided with the great age of European voyages of exploration and conquest.

Successive European seafaring powers mapped and claimed the Pacific world: the Portuguese and the Spanish in the sixteenth century; the Dutch in the seventeenth; the British and French in the eighteenth. By the end of the nineteenth century, the Pacific had been parcelled out among the empires of Britain, France, Holland, Germany and the United States. After World War II, the United States emerged as the dominant Pacific power, with decolonisation and the troubled path towards Western forms of democratic rule and economic sustainability dominating the politics of Pacific nations.

Lansdown’s aim is less to trace these complex histories of imperialism, colonialism and indigenous self-determination than to establish how ‘the Pacific’ has served as a geographical, scientific and imaginative locale within broad Euro-American intellectual developments. His anthology’s primary texts have been written by the usual suspects when it comes to the Western historiography of the Pacific, with the occasional omission in the eyes of this reader (admittedly, anthologies are about personal choice) and some gems from lesser-known commentators. Included are lengthy extracts from the works of explorers (such as de Quirós, Cook, Bougainville), scientists (Banks, Darwin), philosophers (Diderot), anthropologists (Malinowski, Mead), artists (Gauguin) and numerous writers (Melville, Stevenson, London, Mailer), as well as those of a host of colonial administrators, missionaries, journalists and soldiers. All are strangers, in varying degrees, to Pacific cultures, with indigenous responses mediated entirely through Western observations.

The selections are arranged into nine thematic and loosely chronological chapters, each intro-duced by intelligent and often illuminating introductory sections. They span the South Sea Bubble to the H-bomb. In between, Lansdown examines the unique role of the Pacific Islands and Australia in the development of scientific theories of evolution; the struggles over religion; and the burgeoning colonial enterprise, with the Pacific the ‘backyard’ of the white settler societies of the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. Threading these topics together are shifting Western ideas about the diversity of human existence and the issues of race. Pacific encounters, as those with the other new worlds of the Americas, made it difficult for the West to ignore the differences between cultures, and raised questions about the relationships between nature and civilisation.

European engagement with the Pacific coincided with the philosophical underpinnings of the Enlightenment and its concerns with the historical and moral development of the human condition. Rousseau’s romantic belief in the innate morality of human societies and in the mythology of the ‘noble savage’ was to prove extraordinarily influential. The inhabitants of Tahiti, the quintessential island paradise, exemplified this ‘natural’ nobility.

Equally persistent in Western thought was the idea of the ‘fatal impact’ of European contact upon island societies. Doubts about the benefits of European goods and social mores were eloquently expressed by the explorers. ‘Our shame as civilised Christians,’ wrote James Cook, is ‘we debauch their [the Islanders’] morals … we introduce among them wants and perhaps disease … which serve to only to disturb that happy tranquillity which they and their forefathers enjoyed.’

As European attitudes changed during the nineteenth century, the indigenous peoples of the Pacific were no longer regarded as having fallen, swiftly and irreversibly, from a state of grace. Instead, they were most often characterised by the West in terms equated with ‘savagery’: crude, childish and racially inferior. The emerging fields of ethnology, with its systems of classification, and of anthropology, with its methods of fieldwork, recording and collecting, were to flourish in the Pacific. During its formative decades, anthropology was to find an intellectual home among the small communities of Melanesia. By the early twentieth century, the mass readership of Margaret Mead’s anthropological studies of Samoa and New Guinea, with her emphasis on sexual practices and how these ‘lessons’ could be applied more widely, reinforced existing Western preconceptions about the sensuality of traditional Pacific cultures.

Landsdown’s penultimate chapter introduces what he calls the ‘literature of the colonial interregnum’ – ‘a sentimental and moral era … falling between imperialism and the postcolonial period ushered in by the Second World War’. He identifies a common narrative structure across hundreds of memoirs of colonial service: the story of a sophisticated, idealistic bureaucrat sent to ‘do a job’ in the Pacific, in an administration of benign paternalism rather than of active colonial rule, and where the seductive fantasy of the South Seas is reworked to full effect.

But for combatants in the Pacific War (and Lansdown’s extracts are all from Americans), the islands were most frequently characterised as alien and isolated, places of hostile environments, fantastical only in their horror and desolation. In Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead (1948), men of an infantry platoon stationed behind enemy lines on a fictional island see a vision of paradise not around them but above, as the clouds of a tropic sunset formed

a sensual isle, a Biblical land of ruby wines and golden sands and indigo trees. The men stared and stared. The island hovered before them like an Oriental monarch’s conception of heaven and they responded to it with an acute and terrible longing … For a few minutes it dissolved the long dreary passage of the mute months in the jungle, without hope, without pride.

These bleak wartime writings are a prelude for a selection on the West’s postwar disillusion with a Pacific region seemingly spoiled by the effects of tourism and modern consumerism, as in the rubbish that Evans was to describe at Ebeye.

Strangers in the South Seas is a thoughtful and rewarding anthology, and includes some beautifully reproduced illustrations. Lansdown’s commentary is tightly argued, and many of the generous extracts require careful reading. This is essentially a scholarly collection intended for university courses rather than the sort of book that can be cursorily digested. For those with an interest in how the idea of the Pacific has functioned as a ‘distant mirror’ for the West’s intellectual preoccupations, it is highly recommended – even if it is not, like the Pacific itself, for the faint-hearted.

Comments powered by CComment