- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Non-fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Missing iconotypes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

At the centre of this book is the story of the attack on the World Trade Center towers in New York on 9/11. Terry Smith’s focus is architectural: what does it mean for buildings that are supposed to shelter and sustain our lives so spectacularly to collapse? The WTC’s destruction raises this question so singularly, not only for those who immediately suffered – traumatised by the obliteration of family members or their own escape from death – but for contemporary Everyman and Everywoman, who encountered the WTC not first-hand but as an image, what Smith calls an ‘iconotype’ in an ‘iconomy’ of architectural images.

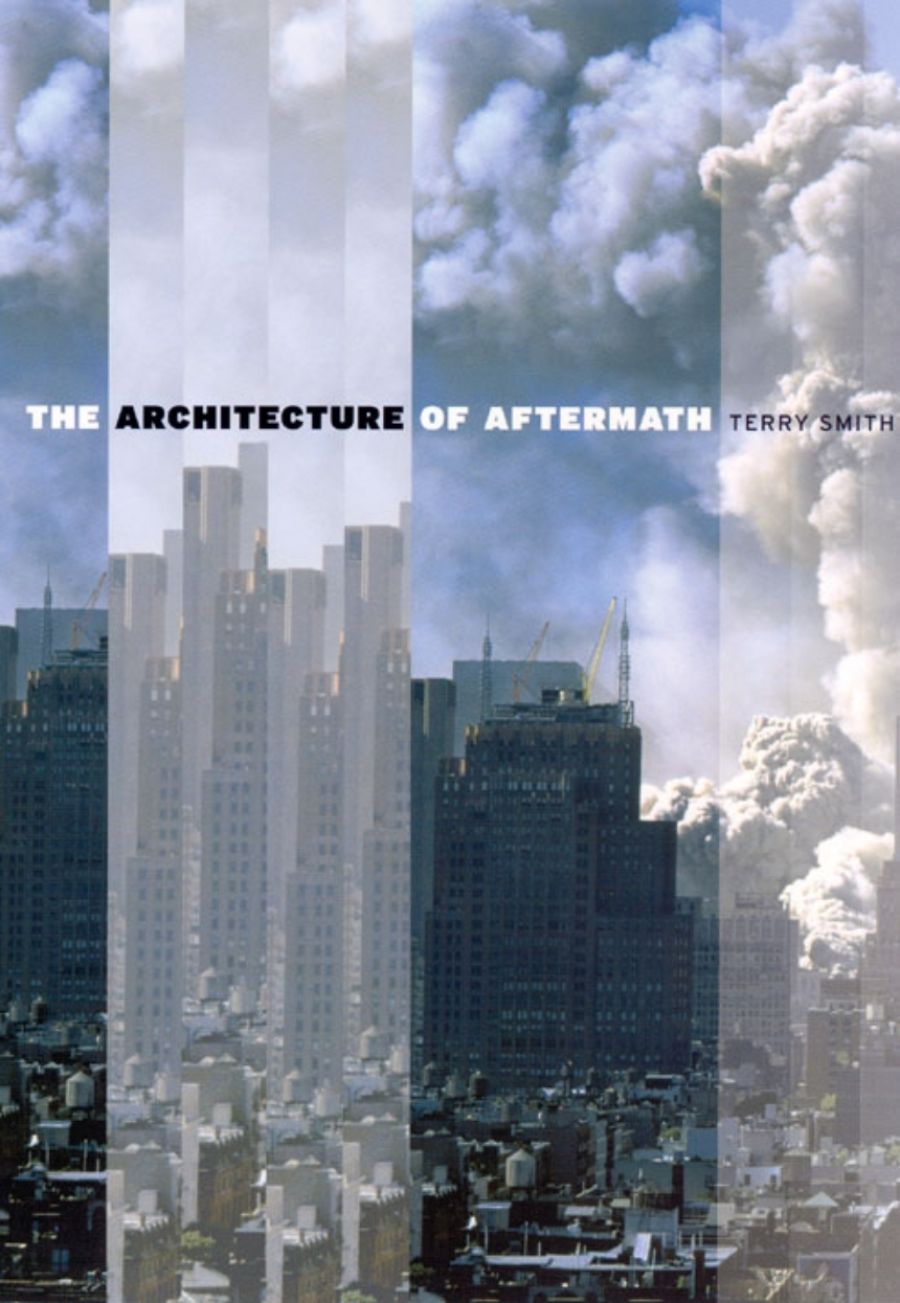

- Book 1 Title: The Architecture of Aftermath

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Chicago Press, $54.95 pb, 259 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/Gj3JaE

The question of the WTC as an image is a complicated one. Disavowed by architectural historians during its life, the WTC was also little loved by the New York public, which never embraced it as it did older giants such as the Empire State or the Chrysler. Minoru Yamasaki, the architect of the WTC, naïvely wished that his building would be a symbol of international harmony. Although by the time it was destroyed the centre was tenanted mostly by large operators in the New York financial sector, it had been originally intended to accommodate international companies undertaking trade into the United States. But the WTC’s realisation required the destruction of sixteen acres of lively urban fabric already inhabited by immigrant traders and apparently called the Syrian Quarter. The WTC’s construction was an urban renewal project already outdated by the time it was completed in 1974, a decade after Jane Jacob’s withering attack on such large-scale reconstruction in The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961). The inhumanity of its imposition on the urban continuum was matched by the WTC’s meagre aesthetic: huge square plan, narrow windows, 110 featureless storeys – not once but twice. Those who worked in it particularly despised it: its structural design allowed endless floor-plates with all the charm of an accounting spreadsheet.

But despite the public and professional distaste, the destruction of the WTC led to widespread mourning not just for those who died in the building but for the building itself. There were immediate, emotive demands that it should be rebuilt. Even after a period of many months of sober reflection, the designs proposed to the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation (LMDC) by seven consortia of reputable architects remained marked by the aloof giantism of the Yamasaki design, and in most cases by the doubled towers. Why the mourning? Of what was the WTC an image? It was an exaggerated image of the compromised socio-economic régime within which our lives, the lives of Westerners at the beginning of the twentieth-first century, have been made; perhaps akin to a family photograph or one of a school class. The aftermath, then, referred to in the title of this book is certainly the aftermath of 9/11, but it is also the aftermath of modernity, of the world that made us.

Smith’s WTC analysis is compelling. His account of what has been entailed for architectural culture in the building of the WTC, its destruction and the proposals for rebuilding on its site shows that these phases of the place’s history cannot be separated. His assessment of the merits and problems of the design by Daniel Libeskind, selected by the LMDC, is acute. Particularly important is Smith’s insistence in his conclusion that future construction on Ground Zero will only succeed to the degree that it is open to reconciliation in the tradition of societies built on immigration. Lest this sound vague, Smith is specific and audacious: the attackers of 9/11 should be remembered on the site along with the victims; a mosque should be incorporated in the new Ground Zero facilities.

Smith’s analysis of the WTC is preceded by four essays on other architectural icons: the Guggenheim Bilbao; the Sydney Opera House; the Getty Center in Los Angeles; and the Jewish Museum in Berlin. These enable Smith to establish what he sees as the key architectural trajectories between the fall of the Berlin Wall and 9/11: ‘open-form spectacle, past-modern quotation, engineering featurism, and grounding the contradictions.’ The architects who are specifically connected to each of these are in turn Frank Gehry, Richard Meier, Santiago Calatrava and Daniel Libeskind. Each of the essays that led to this schema is a fine thing, well balanced and acutely observed. For example, while the Gehry designed Guggenheim Bilbao has been cited frequently before in connection with the economic revival of the Basque regional capital, Smith draws our attention to the simultaneous depression in explicitly local arts initiatives, and queries how long Gehry’s building and the museum it houses will attract tourists; how long its surfaces will look shiny. He nevertheless clearly loves the bravura of Gehry’s architecture.

The picture that Smith paints of the architectural scene in the 1990s through these essays could readily be challenged. Gehry, Meier, Calatrava, Libeskind by all means, but there were other important architectural lines: the material minimalism exemplified by Tadao Ando; the explorations of programmatic density in the work of Rem Koolhaas, OMA and connected Dutch groups; the manipulated, often figurative surfaces of Herzog and De Meuron. Smith mentions each of these architects only in passing, and while there is no reason for him to be encyclopedic, I think wider discussion of work by such architects would offer a great deal in relation to the issue ostensibly at the heart of The Architecture of Aftermath: how is architecture an image?

This is a shortcoming of the book. To think of architecture as an image requires us to think of the conditions, contexts and even technologies of the image’s reception. This is something Smith barely does. Is there any monument he knows only from the photographs, like the rest of us? From his text, I don’t think so. Rather, he always retains the critical stance of the ideally engaged art critic, necessarily encountering his quarry as directly and perceptively as possible. But the conditions of architecture’s reception range from something akin to this – the critic’s first-hand encounter undertaken with full knowledge of the architect’s oeuvre and the project’s history – to that of the distracted Australian television viewer barely apprehending a passing shot of the WTC, a cipher of New Yorkness in an old American cop show. Reception is mostly distracted, weak: even a building’s occupants or those who glance at a famous monument may only be fitfully aware of what they see. Writing on this in his famous essay ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’ (1936), Walter Benjamin argued that it was the collective nature of this distracted experience that made architecture a truly political art. We need to think more about this condition if we want, as Smith does, to make the study of visual culture pertinent to current political circumstances.

Comments powered by CComment