- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Maud's murk

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Britain’s Prospect magazine recently canvassed a number of leading thinkers on the question of what, in coming decades, would replace the great twentieth-century schism between left and right. In an overwhelmingly pessimistic field, the contribution of Pakistani scientist Pervez Hoodbhoy stood out in its cold-blooded concision. ‘Global and national politics will turn simple and Hobbesian,’ he predicted. ‘In the interim, energy hunger will drive the US and European countries to squeeze out, and steal, the last drops of oil from under Muslim sands. As bridges between Islam and the west collapse, expect global civil war and triumphant neo-Talibanic movements circling the globe.’

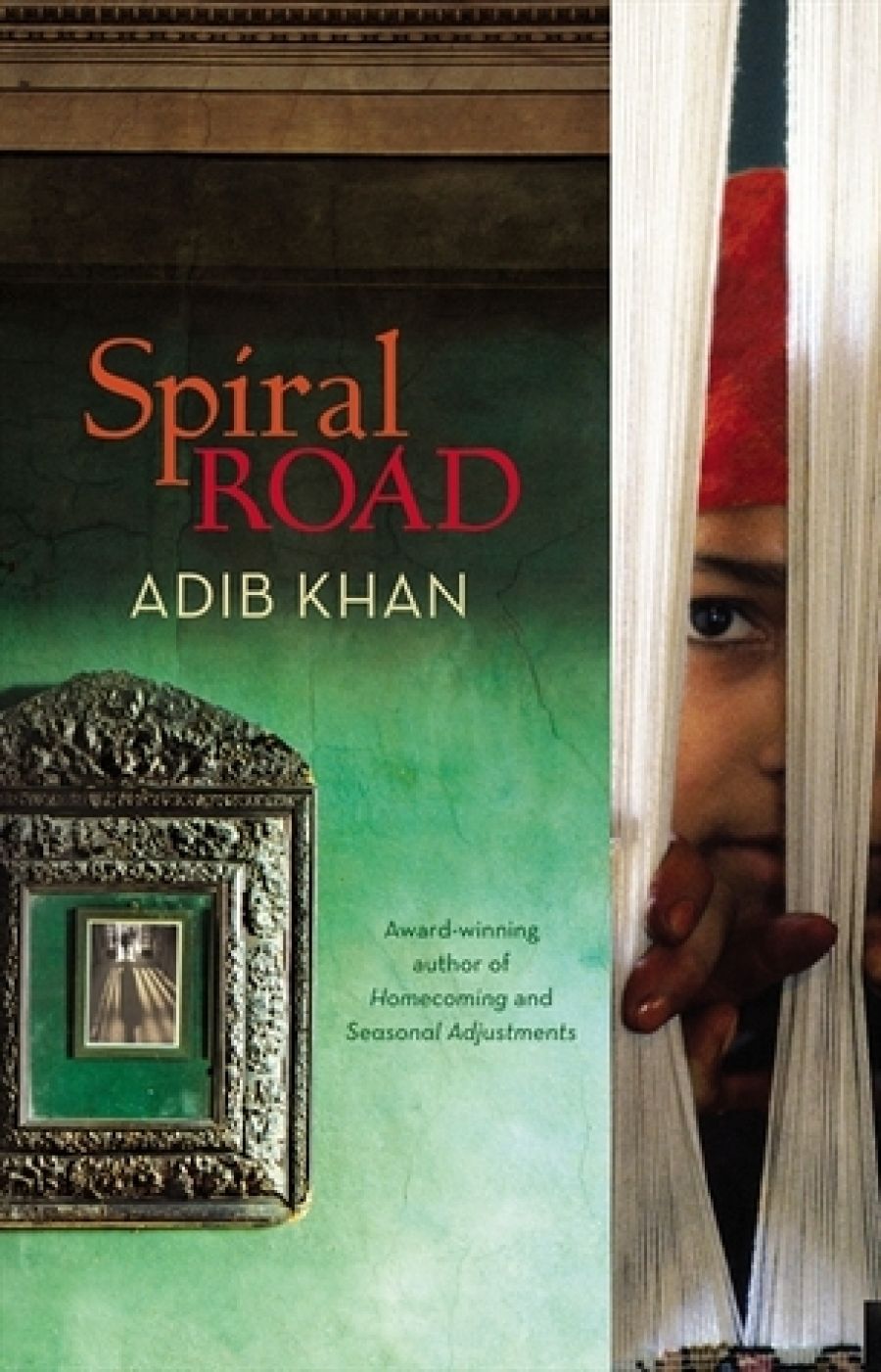

- Book 1 Title: Spiral Road

- Book 1 Biblio: Fourth Estate, $27.95 pb, 362 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/2r9zOD

Spiral Road, Adib Khan’s fifth work of fiction, is a worthy attempt at humanising this Manichean abstraction: a novel tracing the experience of a man standing in the middle of one such bridge as it begins to crumble. That it fails is less an indictment of Khan’s gifts as a writer – although there are weaknesses here – than an acknowledgment of the difficulty of describing the pure cerebral white-out of the fundamentalist worldview. The novel is an open, messy, quarrelsome form; but the terrorist mind is a closed perfection. Our narrator, Masud Alam, is a man haunted by his own insubstantial self. As a young student in what is now Bangladesh, he was a leftist, a university agitator and, eventually, a freedom fighter. His experience during the struggle for independence shook him out of certainty, however: no political or religious programme was worth the death of innocents. He fled to Australia, abandoning his beliefs and his large, rather grand family, and hunkered down.

Years later, we meet him leading a placid half-life in suburban Melbourne, eking out his days as a librarian and basking in a fragile contentment largely based on self-imposed amnesia. But the man who considers himself an Australian citizen, a rationalist, a non-believer and an educated member of the Universal Civilisation of the West cannot ignore the daily reminders of his difference. The 9/11 attacks only etch these in sharper relief. The news that his father, Abba, has been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, is the twitch on the thread that draws Masud home, to a country and a family at once familiar and alien. Indeed, Abba’s condition stands in for the one afflicting modern-day Bangladesh – the old colonial coherence breaking down – as well as Masud’s own threatened sense of identity. The Alam family’s wealth and social standing have diminished with the intervening years, and yet certain expectations and patterns of behaviour are still enforced. Masud’s wastrel uncle is cut off from his family for contemplating a socially unsuitable fourth marriage. His mother, querulous at the decline of a more certain world, clings to traditional domesticity. A divorced sister lives a shrunken life of public disgrace.

But as he makes an uneasy re-entry into family life, Masud comes to realise that others have changed in more disturbing ways. His brother Zia, a successful, Americaneducated professional – the family anchor – has become more radical in his politics: he is providing clandestine shipments of medical supplies to the Pakistan–Afghanistan border. And yet he has only dipped a toe compared with his son, Omar, who also went to the United States, suffered interrogation at the hands of American security services, and returned to Bangladesh, determined to create a domestic terror cell.

Omar provides the red meat of the narrative. Knowing of his uncle’s past, he seeks to draw Masud into the jihadist orbit. Masud is repelled, but also admires his nephew’s clarity of purpose. The drama of the novel lies here, in the question of which path Masud will take. When it arrives, the resolution feels cheap – aesthetically gimcrack in a way that retrospectively illuminates the novel’s flaws. Masud’s voice is kindly, intelligent in a melancholy way, and sometimes elegant; but more often it is stunned by its own confusions. And yet confusion is just another item in the novelist’s rhetorical toolbox. Even the depiction of Masud’s mental disorder must be carefully shaped. Instead, when he flails around for some moral purchase, we sense the author is, too. It is unfortunate that Spiral Road should address subjects already broached with such grim authority by V.S. Naipaul. His last novel, Magic Seeds (2004), also describes the experience of an individual’s reluctant involvement with a terrorist group. Naipaul captures perfectly the sense of panic felt by a man who, torn between East and West, makes a decision based on a flabby and suspect idealism, and ends up indentured to murderers. In its pages, we are offered a portrait of confusion controlled by a merciless intelligence and literary craft. A better version of Khan’s book would explore in greater detail Masud’s own time in such a group. It would also use character and plot to drive the novel forward, instead of shunting it along by resort to bare explication. In Naipaul, the confusion is part of a larger insight into mass political movements. In Spiral Road, we only stumble, blindly, within Masud’s personal murk.

Comments powered by CComment