- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Young Adult Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Negotiating hardships

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Two new young adult novels explore the complexities of family. While Maureen McCarthy’s Somebody’s Crying details a daughter’s painful loss of her mother, Alyssa Brugman’s Girl Next Door negotiates the hardships of teenage life while coming to terms with family bankruptcy.

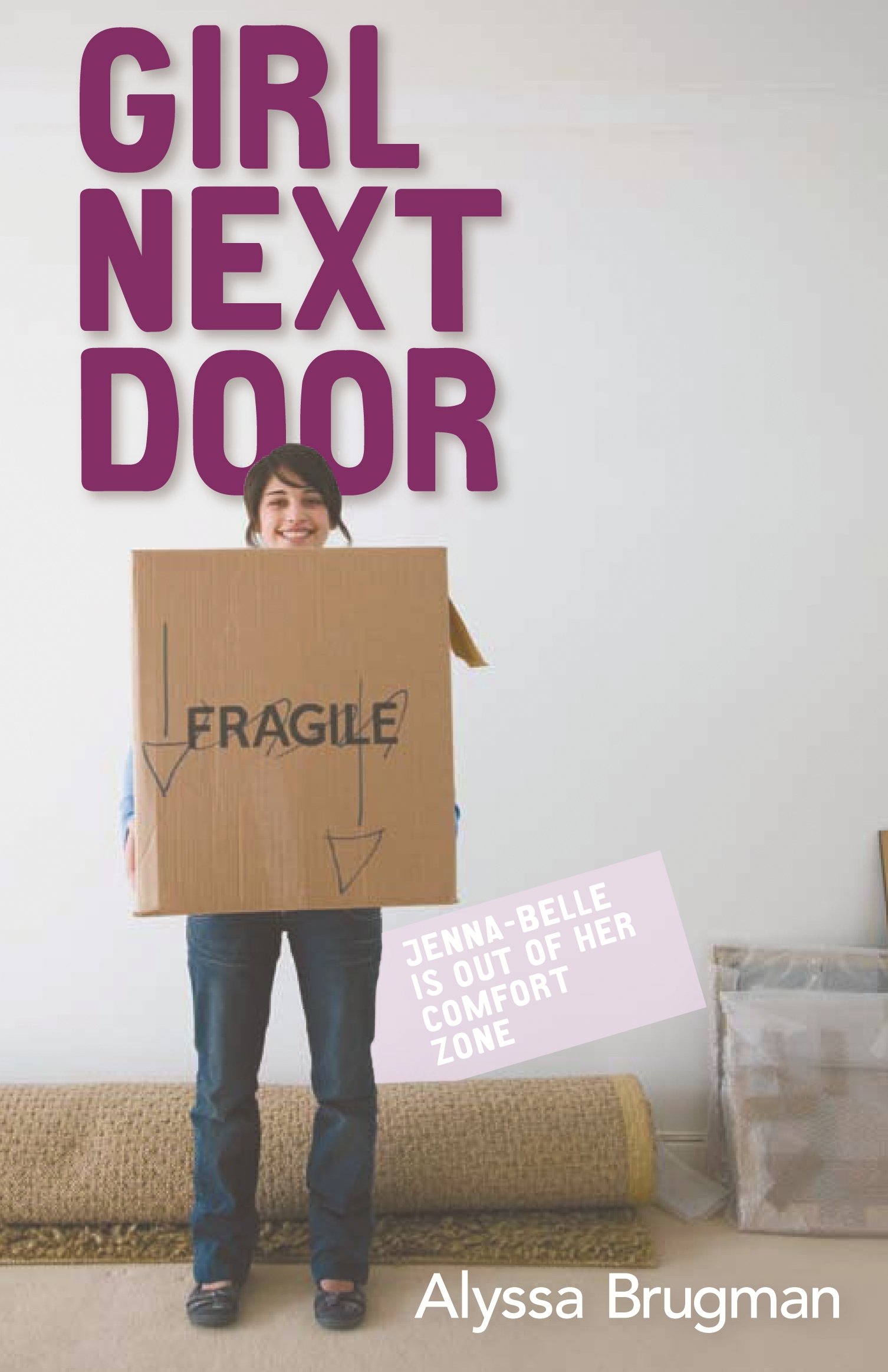

- Book 1 Title: Girl Next Door

- Book 1 Biblio: Random House, $19.95 pb, 274 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

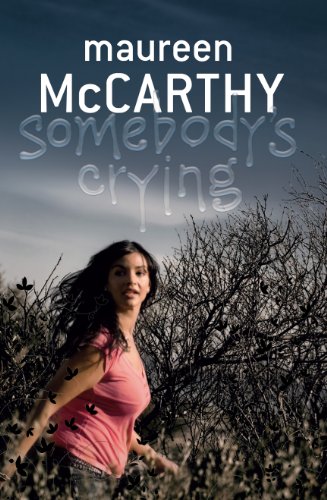

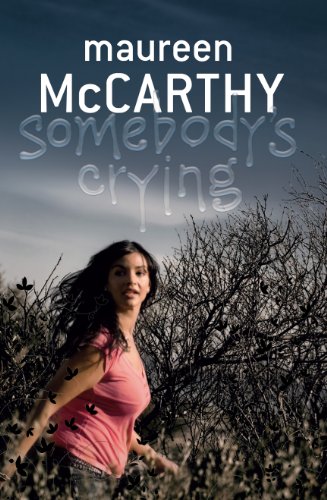

- Book 2 Title: Somebody’s Crying

- Book 2 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $22.95 pb, 371 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

The novel begins when Alice, Jonty and Tom return to Warrnambool, drawn together by their connection to the unsolved crime: Alice as the daughter searching for answers about the murder of her mother; Jonty as the accused; and Tom in his complex relationship with the deceased. Provocative and well-positioned flashbacks illuminate each of the character’s secrets as the mystery – deliberately paced – slowly unravels.

The minutiae of life in a small-town is exceptional: in the eccentric inhabitants and local gossip McCarthy captures Warrnambool. That said, the novel would have benefited from a more careful depiction of this vicious crime’s impact on an isolated community, rather than focusing exclusively on the three characters involved.

McCarthy is expert in portraying the fraught transition from adolescence to adulthood; Somebody’s Crying develops some intriguing characters – the multifaceted Jonty being a standout. Tom, the primary narrator, is prone to melancholia and dramatics – ‘Tom can’t shake the feeling that he’s lived most of his life already […] The main game has already been played and … he lost’ – which becomes tiresome. Minor characters are used to great effect, keeping this dark novel from becoming too morbid. Alice’s friend Eric, in all his absurdity, is a delight.

However, the novel is occasionally weighed down with clichés and such florid prose as:

Sadness flies in from nowhere on a volley of arrows, unexpected, sharp and precise […] There goes another one, straight to the heart, dropping its poison dart. The venom floods slowly outwards and upwards until her eyes sting with it...

McCarthy remains one of Australia’s most popular young adult novelists. While often dealing with contentious issues in her fiction, she is admired for her measured and objective storytelling – McCarthy never slips into the didactic. She always maintains authorial distance, leaving the characters to take shape and speak for themselves.

Alyssa Brugman’s eleventh novel, Girl Next Door, opens with teenage Jenna-Belle pondering the recent changes to her upper-middle class life. Her mother was recently promoted and her father left his executive job to start a new business (‘empire’). But things go awry when the business fails and Jenna-Belle’s mother falls pregnant. The family is soon bankrupt, having ‘borrowed as much as they could’, and, among other degradations, they are forced to rent out rooms in the family home.

With her father disappearing ‘to the country’ and her mother unable to afford the exorbitant school fees, Jenna-Belle is forcibly removed from the exclusive Finsbury School. With little else to do, she strikes up an unusual friendship with Bryce Cole, her newest housemate. This is one of the more charming relationships in the novel, as the fun but irresponsible Cole teaches her the ins and outs of horseracing. Brugman excels in these scenes, capturing the excitement of the racetrack and the punters. (Horses are often at the centre of Brugman’s novels, particularly her pony book series for younger readers, including the award-winning For Swap or Sale, 2005.) In fact, gambling metaphors propel Girl Next Door: Jenna-Belle, predictably, falls into the trap of believing, ‘If you’re not willing to lose it then you just wouldn’t bet it in the first place.’

Jenna-Belle is a provocative yet ultimately unlikable narrator. Her attitudes are rather hit-and-miss: occasionally humorous and astute, they are at other times mildly impolitic in their Dickensian class feel (almost all the poor characters are ugly or cruel). For all her quick wit, Jenna-Belle is prone to selfishness and outright ignorance – ‘The police might force me to go to a public school. I’ll probably get stabbed three times and be on crack by lunchtime’. While this is obviously Brugman’s intention, such posturing begins to grate, particularly when Jenna-Belle breaks into irritating teenage-talk, adding ‘Hello!’ to the end of sentences.

One tasteless scene includes a conversation between Jenna-Belle’s brother Willem and their neighbour, Declan. Willem explains why the boys never became friends: ‘I always thought Declan was, like a … you know […] Gay, or whatever. You know how gay guys always seem to have girl friends?’ Rather than repudiate this homophobic statement, Declan quickly clarifies that he is heterosexual. ‘Oh. Sorry, man,’ Willem replies. ‘But, you have to admit that you seem gay.’ This superfluous discussion adds nothing to the narrative – and, never mentioned again, raises all kinds of disconcerting questions as to why Brugman included it at all.

The novel’s ‘family values’ agenda is clear from the beginning: a family loses each other amongst its consumer-capitalist lifestyle, only to discover, finally – and unsurprisingly – what is really important. Despite its earnest message, Girl Next Door is let down by its unpleasant and vacuous characters, with whom it is almost impossible to empathise.

Comments powered by CComment