- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The missing Rumpole

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

To become associated, even identified, with a role or a certain kind of role may ward off the financial uncertainties of an actor’s career, but it undoubtedly also brings its limitations. Remember how ineffably lady-like Greer Garson appeared in her MGM heyday: I recall watching her narrow her eyes in Mrs Miniver and thinking that she could play Lady Macbeth if someone gave her the chance. No one ever did. Leo McKern wasn’t quite so effectively imprisoned by his ‘Rumpole’ persona, but it is at least on the cards that he will be remembered with such tenacity for nothing else.

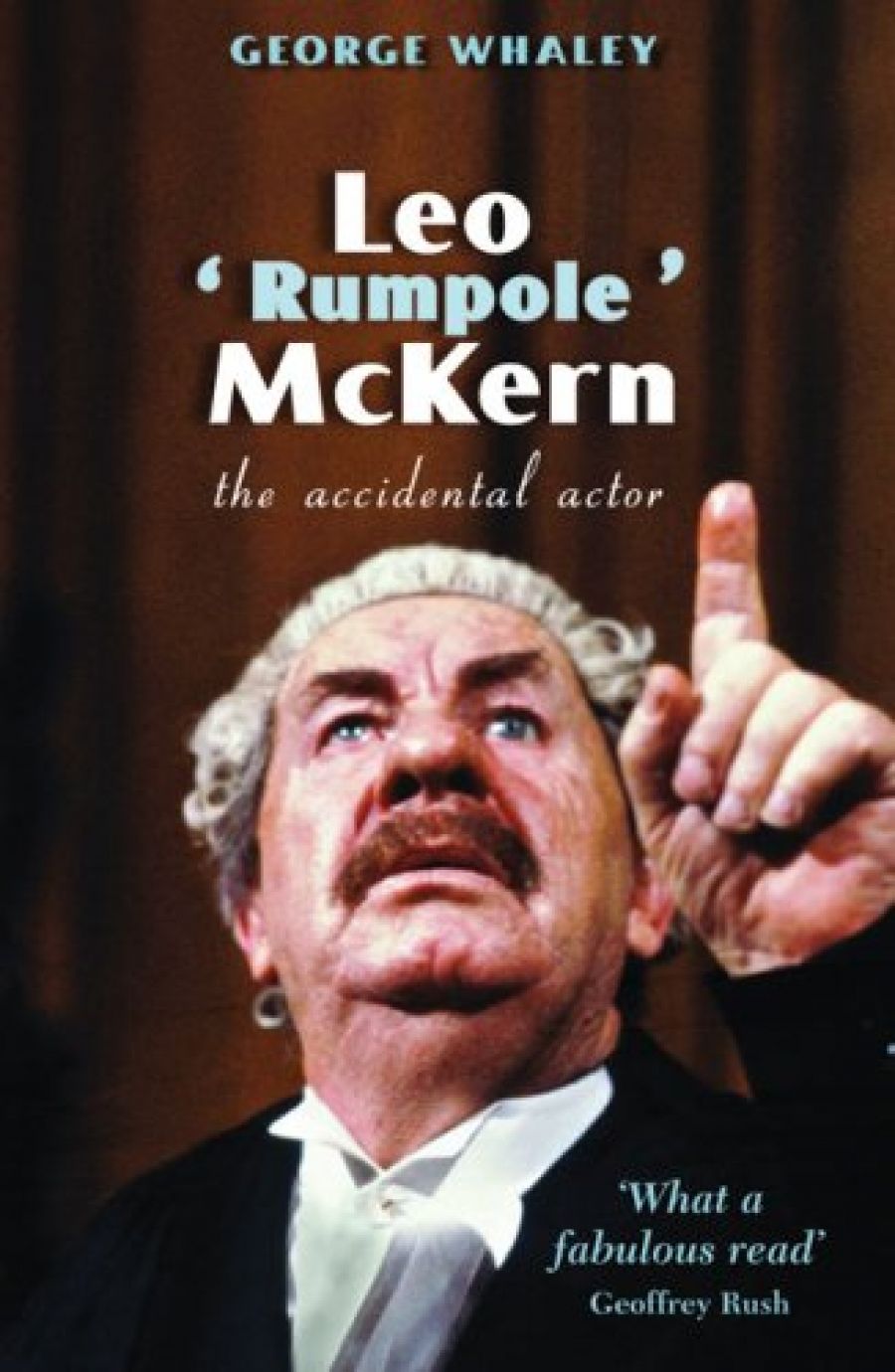

- Book 1 Title: Leo ‘Rumpole’ McKern

- Book 1 Subtitle: The accidental actor

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $39.95 pb, 297 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

From working-class Sydney origins – his father was a skilled tradesman whose family thought he had married beneath him – McKern was skimpily educated and always regretted this. He lost an eye when working in a refrigeration company in his mid-teens, and more or less stumbled into acting, war service and an unsuccessful first marriage, before heading off for England in pursuit of actress Jane Holland, who would become his wife for the next fifty-odd years. The diaspora of Australian acting talent in the years following World War II has now been well recorded, but in McKern’s case it was essentially Holland he was pursuing, and she seems to have coped with giving up her own career to assume the roles of wife and mother without apparent bitterness.

Short, pudgy-featured, plump and later, frankly, fat, McKern was an unlikely starter as conventional leading man, but there was – in life, we gather, as well as on stage or screen – a beguiling quality, a shrewdness and a raconteur’s style that made him attractive company. Not given to making close friends, he seems nevertheless to have been liked and respected as a working colleague. After limited stage experience in Sydney, he found work in England surprisingly quickly and, as Whaley reports, people, including the queen, either forgot or never knew he was Australian.

Whaley is right about the sparseness of work on offer in postwar Australian theatre, and there was virtually none in film, but he may be unduly severe about what is now available. McKern found work in all the British acting media, and like most actors he almost never turned anything down, setting the pattern for the rest of his fifty-year career. There was some notable stage work, in everything from Shakespeare to Brecht, and he appeared in four dozen films; but Rumpole will probably dwarf them all in the collective memory, though the stage was his first allegiance.

His Iago in Othello was much praised, but one doesn’t get much sense of what it was like. In a very different mode, he made something memorable of the Common Man in Robert Bolt’s A Man for All Seasons, and thirty-odd years later as the tippling photographer in a charming revival of J.B. Priestley’s When We Are Married. It is difficult to evoke a theatrical performance, but, as Jonathan Croall’s superb biography of John Gielgud (2001) shows, it can be done. Too often here – I presume Whaley has not seen these performances – it is a matter of no more than a brief outline of the play’s plot, a list of other cast members and a selection of reviews. Plays vanish into the annals and into people’s memories, unlike film and (much) television, which have a longer life as a species of ‘text’: that is, they exist in replicable forms that we can watch again.

My point is that Whaley does not seem to have availed himself of this possibility. I can almost forgive him for the bland account of so many theatrical occasions of which the recollections are bound to be evanescent, but why has he not looked more carefully at the ‘evidence’ of the filmed performances? If there is some excuse for the scrappiness of the writing about McKern’s theatrical career, there is less for a similarly meagre account of his film role-call. Again and again I found myself wondering, has he actually seen this film? For instance, of the Dirk Bogarde spy-spoof, Hot Enough for June (1964), his only critical comment is, ‘By all reports, the casting was better than the script’. Why is he relying on ‘all reports’? Why has he not looked at the film, readily available as it is? Too often, with films, he has been satisfied with second-hand opinions when primary research would not have been difficult.

Irritatingly, there is no chronology of performances, and the plays (and films and television roles) are listed in the index under ‘A’ or ‘The’, if that is their first word, and, if not, under the title’s first letter. This is the least user-friendly approach to cataloguing an acting career I have ever found. An appendix giving dates and key credits for theatre, and a filmography for cinema and television appearances, would have obviated the need for much of the recital of titles and names which clogs the narrative, and more space could have been made for analysis of why this or that performance was significant in McKern’s career. Further, Whaley adopts the conventional view that film acting is never as rewarding to actors as the stage is. This may be so, but he needs to give more sense of why. Do stage actors take on films merely for the money?

The author makes claims for, but does not really demonstrate, McKern’s ‘complexity’ as a man. He suggests that his subject was self-effacing but prone to irritability, that he lived modestly but loved the luxury of multi-car-owning, that he was wary of friends but that people were fond of him, that he loved acting but refused to talk about it, and so on. Too often these insights remain at the level of immiscible assertions, when they might have been the basis for a more demanding assessment of the man. How did the actor, the husband, the father and the professional colleague add up to some kind of whole? Perhaps they didn’t. I wanted the author to work harder at assembling what he had learnt about the actor he would ultimately direct in Dad and Dave – On Our Selection (1995), opposite Joan Sutherland in her only film role. I would have valued this over the undigested slabs of text about, say, World War II, angry young men, and the origin of ‘thespian’.

Stylistically, the book is hearteningly free from errors (though someone should have told him about Howard Hawks, not ‘Hawkes’); and the clichés (audiences ‘stayed away in droves’ and ‘comfort zones’) are probably outnumbered by the felicities (‘an actor with an unreliable memory is in the professionally terminal condition of a sprinter with gout’). Overall, though, the book is breezily undistinguished; it is an easy read (rather than a ‘fabulous’ one, as Geoffrey Rush hyperbolises on the cover), but one keeps thinking there is more to Rumpole than has met Whaley’s eye.

Comments powered by CComment