- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Essay Collection

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Obdurate guilt

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

This is a book about a very specific past, that of the Third Reich, and the way in which it produced guilt in the next generation, but its lessons can be generalised. Bernhard Schlink shows how that guilt has withstood the institutional strategies of history, law and politics to erase it. Schlink, born in 1944, belongs to the generation burdened with the moral repercussions of the war and the Holocaust. Many of the parents, teachers, judicial officers, bureaucrats and professors who rebuilt Germany were implicated in Nazism, and many young Germans – Schlink among them – found themselves guilty by entanglement. This theme runs centrally through Schlink’s fiction – notably The Reader (1997) and Homecoming (2008) – and now through these six essays, given originally as lectures at St Anne’s College, Oxford.

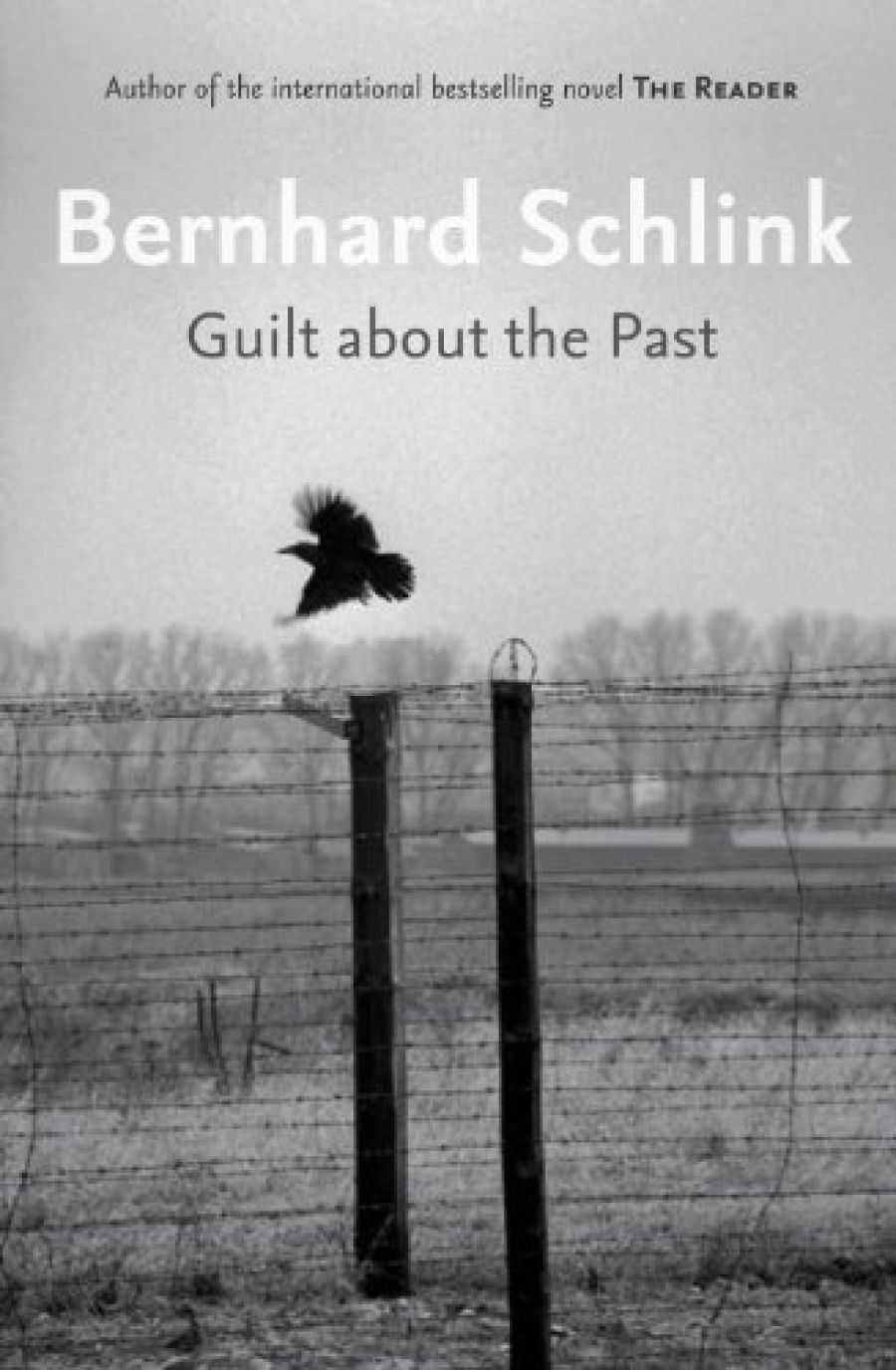

- Book 1 Title: Guilt About the Past

- Book 1 Biblio: UQP, $26.95 pb, 141 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

These lectures stand by themselves, but Schlink acknowledges that they belong to his abiding concerns. The Reader is a kind of parable for the condition that Schlink describes for his generation. To discover, over and over again, that the significant people in one’s life had, by their very significance, enmeshed one in their guilt, that their nurturing, concern and sacrifices concealed a terrible truth, is horrifying. Schlink depicts this horror creatively in his fiction, and discursively here. In The Reader, Michael’s loss of innocence to the older Hanna, who is morally as well as functionally illiterate, is a parable of this condition. His story of intergenerational taint is an allegory for his generation’s predicament in disengaging from guilt.

Schlink’s community of guilt is constituted in the first generation by perpetrators of Nazi crimes, but also by those who did nothing to stop them. The latter category seems odd: as Schlink acknowledges in his second essay, under brutal régimes ‘there comes a point when the ethics of opposition survive only in quixotic heroic gestures’. Quite, but this acknowledgment does not undo Schlink’s point, which is amplified in his fifth essay, ‘Prudence and Corruption’. This is an extended discussion of an incident in Schlink’s career as a lawyer in which members of a legal society stay silent in the face of manifest untruth. They are guilty of hypocrisy, of political accommodation when courage was not only called for but would also have done some good – when it would have been neither heroic nor quixotic. Schlink, however, wants to draw the complex picture, so he looks at the good intentions, the prudence behind the silence, the wish not to cause a fuss, to contain damage to the profession and its respectability. Well, if you intend the end you intend the means, and wicked means do indeed corrupt the well-intentioned.

One example of misplaced good intentions is the use of cultural rituals to accomplish the task of dealing with historical evil. Schlink dismisses legal remedies and political gestures as inappropriate to this. He rejects reconciliation by proxy. Only the perpetrators can ask for forgiveness; only the victims can forgive. While he does not mention the recent spate of official apologies, his position can be inferred from his discussion. Similarly, he dismisses culturally safe conventions as ways of dealing with intergenerational guilt. He has been accused of giving Nazi brutality a human face in his depiction of Hanna, but Schlink insists that this is not because he wishes his readers to identify with or to have sympathy for her. Quite the opposite is true. He had to make her character legible, because for him understanding her failure would not be possible if she were a stereotypical brute. Moreover, reconciliation without understanding would not be possible either, so Schlink must go beyond the simple types that constitute our sustaining myths. The truth in fiction is not captured in simplifying conventions. Indeed, as Schlink points out in his second essay, memorialising horrors, such as the Holocaust, in conventionalised ways can reduce them to banality – the very thing Hannah Arendt observed about evil.

There is little comfort in these essays, but much to think about. Schlink explicitly declines to comment on other examples of historical guilt, but his reflections offer insights into the now quite widespread urge to take refuge from the shame of the past in conventional rituals, legal measures and cultural practices. This collection also shows the obduracy of intergenerational guilt in resisting such measures.

Comments powered by CComment