- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: All too obvious

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

On Valentine’s Day, the State Library of Victoria will host its third literary speed-dating dinner, an event that makes explicit something that has long been implicit in contemporary courtship chatter: you can judge a lover by their book. Participants in these events have about three minutes to impress each potential partner with the one book they brought along for show-and-tell. At the first such dinner, one man brought along The Story of O, which at least made it clear that he was there for a good time, if not a long one.

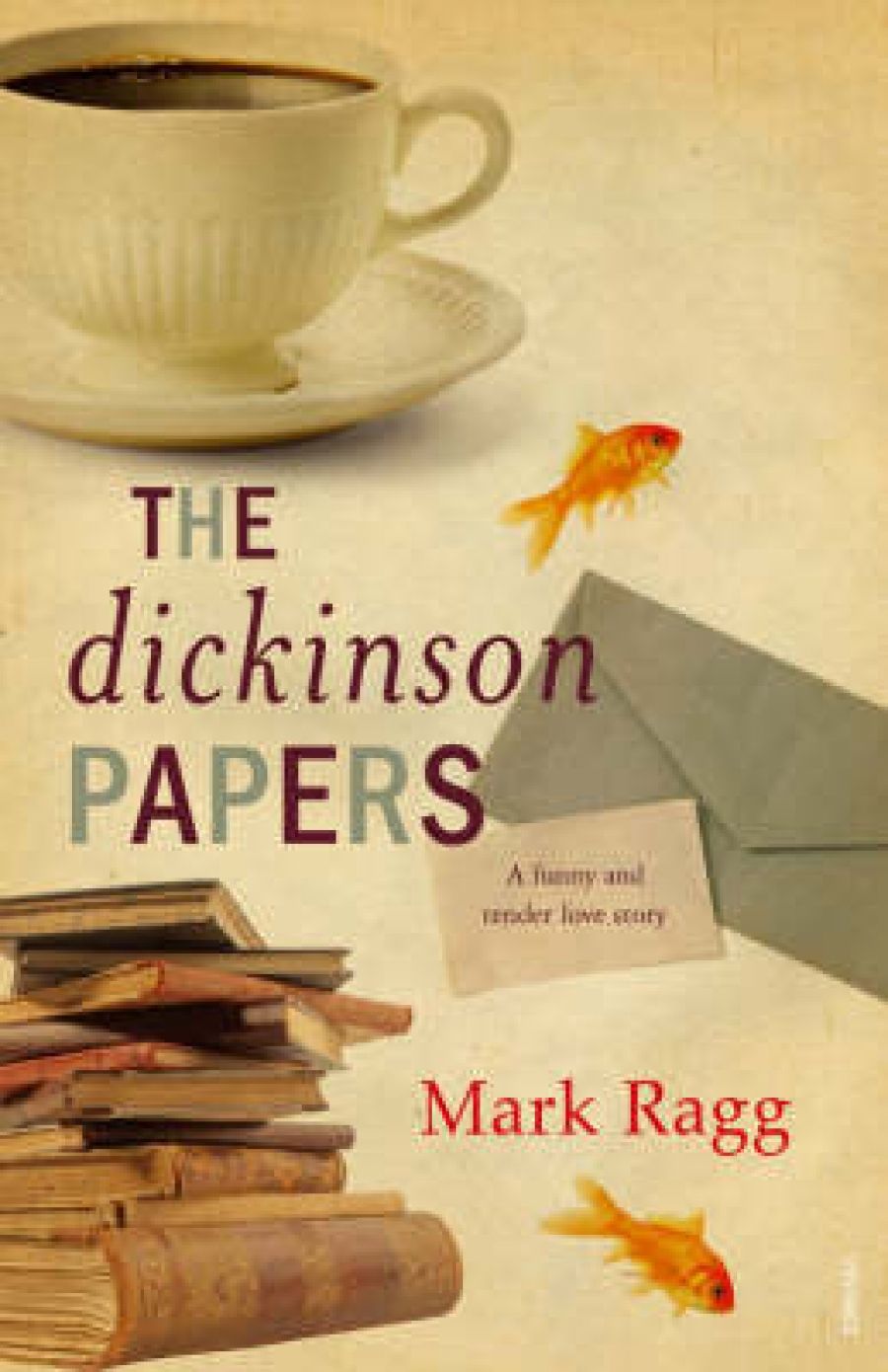

- Book 1 Title: The Dickinson Papers

- Book 1 Biblio: Vintage, $32.95 pb, 315 pp

But literate lovers have been courting each other with book lists for centuries. Even now, despite the distraction of DVDs and iPod, potential lovers will lend one another books. This can save a lot of time, especially if the object of your affection hauls out The Alchemist and starts reading aloud. You can quit before Coehlo starts to colonise your shelves. Conversely, you could both bond over Haruki Murakami, Hunter S. Thompson, or Tim Winton.

Now, what sort of lover would use as bait books about lovers who exchange books? It seems rather blatant to be so meta about the whole exercise, but it might work: there is A.S. Byatt’s Possession or Italo Calvino’s If on a Winter’s Night a Traveller.

Entering the fray is this determinedly quirky first novel, which hinges on a Sydney couple who ‘meet cute’, as they say in the sitcoms, because of their shared enthusiasm for Emily Dickinson. Jock Anderson is a single father, a chronic e-mailer and a mediocre poet. Lola Martine is curator of an exhibition of Dickinson’s papers at the Sydney Library. Or at least, she was, until all the papers disappeared. She writes a snippy letter to the local paper, chiding their ‘books writer’ Warwick de Capra for his sloppy grammar. He then writes to the paper, faulting Lola for using the anachronistic prefix Ms instead of Miss. Direct correspondence begins, and they meet. Together, they work to solve the mystery of the missing papers. If this set-up appeals, you may find this Sydney paper chase diverting. But frankly, just like Lola, this novel isn’t as clever as it likes to think it is, with its cute little footnotes, its bookshelf name-dropping and its plot updates courtesy of deliberately dire newspaper stories filed by the hapless de Capra.

I am not sure that Lola Martine is supposed to come across like a coddled schoolgirl, but she does. For a scholar, she has a giddy crush on her subject, calling her The Divine Ms M, preening over her knowledge of Dickinson’s quiet life and responding to her work with the emotional acuity of an adolescent. In a letter to Jock detailing all the reasons why she loves Dickinson, the actual work rates only a passing mention. Instead we get this:

Well, because she’s a fantastic poet. I love her quirks and rhythms and lack of rhythms and I love that sometimes, no matter how I try, I have absolutely no idea what she is on about. And she hits you hard – ‘I felt a Funeral, in my Brain’. That’s pretty hard to beat. I like a good opening. Jane Austen gave good opening. So did C.S. Lewis.

She then footnotes this reply with the requisite and obvious Austen and Lewis openings. She goes on to talk about Dickinson as a feminist icon with a mean father, but this doesn’t persuade me that Lola is truly cut out for the work of an academic. Yes, she is the novel’s unreliable narrator, but there’s nothing in the dénouement to indicate that she’s supposed to be a fraud who bluffed her way into her job. She has another, more irritating function too: to spoonfeed information about Dickinson to the reader. True, I did not know that the poet had won a prize in a baking competition, but I felt as if the novel had been hijacked by a PowerPoint presentation. The same goes for the many footnotes about Sydney, all aimed at an overseas audience unfamiliar with Harry Seidler, Mardi Gras or, indeed, John Howard.

The other protagonist, Jock, is both more bearable, despite his own poems, and more plausible. He has the standard cultural patina of a forty-something divorcé with a sensitive side. He admires Richard Ford’s The Sportswriter, watches David Mamet films and can quote freely from The Maltese Falcon. Instead of Lola’s pantomime relationship with her mother (a Kath Day avatar with inferior dialogue), we get Jock’s awkward but loving relationship with his three kids. In these chapters is the germ of a different novel, more Richard Ford than Jasper Fforde. But like Jock’s kids, we are not allowed to stay here. Instead, we are sent off on a caper that can only end somewhere all too obvious.

Comments powered by CComment