- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Alive and barking

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Seeing these two anthologies side by side in that obscure corner allocated to poetry by so many bookshops, a casual browser might note that both begin with Robert Adamson’s ‘A Visitation’ and conclude that uniformity rules and one volume will suffice. Not so: a full savouring of the past year’s poetic crop requires both. In fact, ‘A Visitation’ is the only poem common to both selections. Certainly, they share poets – and it is among these twenty that readers are likely to recognise ‘established’ names such as Alan Gould, Kate Llewellyn, Jan Owen, Peter Porter, Philip Salom (all in their egalitarian alphabetical order), but in each case the particular poem selected is different. Beyond that, there is substantial variation in the selection of poets: nineteen of Beveridge’s forty poets don’t appear among the eighty-two present in Porter’s more extensive volume.

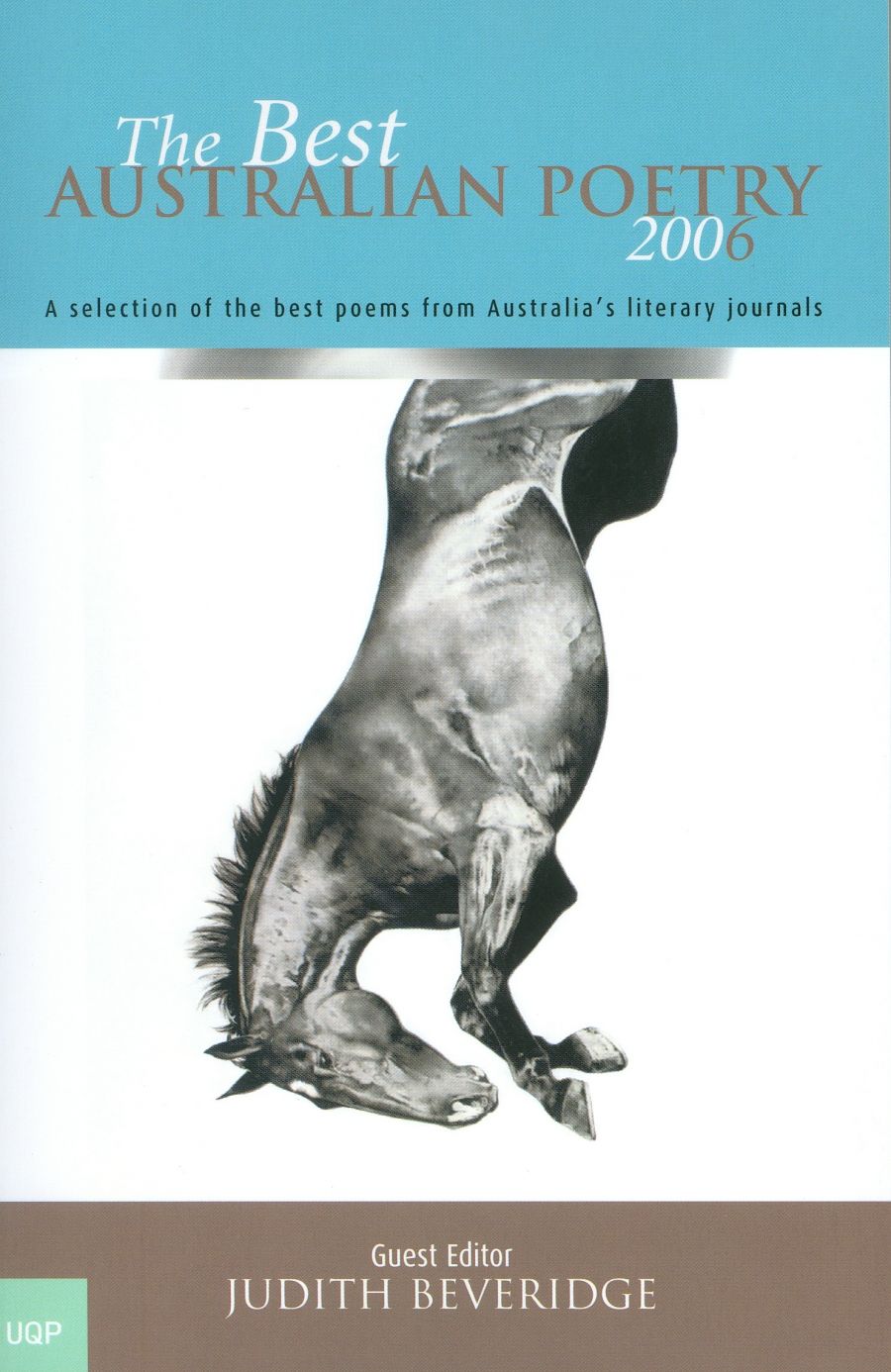

- Book 1 Title: The Best Australian Poetry 2006

- Book 1 Biblio: UQP, $24.95 pb, 143 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/KevjOA

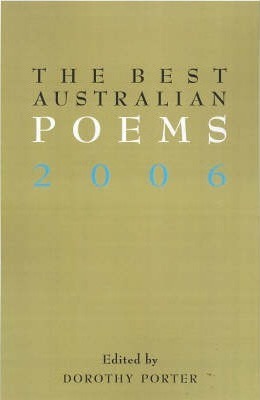

- Book 2 Title: The Best Australian Poems 2006

- Book 2 Biblio: Black Inc, $24.95 pb, 212 pp

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

Some differences of selection result from the different mandate given to each editor. Beveridge, according to the subtitle of her volume, was to draw only on ‘Australian literary journals’. The acknowledgments indicate that this extended to the literary pages of the Australian and the Age, but apparently excluded more ‘political’ journals such as Overland, Hecate or Arena, although these publish a considerable amount of poetry. This is perhaps an unfair quibble. It is not as if Beveridge excludes overtly political poems – vide Philip Harvey’s ‘Non-Core Promise’ or Gig Ryan’s ‘Kangaroo and Emu’ – but it is not accidental, I think, that both these poems attack the soft underbelly of politicians via parodic distortions of the language of politspeak: ‘How to turn the words into gestures, parsing / liperal sirface while it’s business as useyouall’ (Harvey); ‘“We have signed niiine memoranda’” the minister umpteenths out / ramping up his slush fund’s rumpled horn’ (Ryan). In this, they exemplify one aspect of Beveridge’s editorial principles: ‘I decided that my main criteria of selection would be for poems which showed that the poet had an engaged, vital, deep relationship with language; no easy or given one … I wanted poems that showed a thorough coming to terms with the difficulty of circumscribing a position within the dark maw of words.’

Porter had a less restrictive field of choice, drawing not only on anthologies and journals, but also on collections. In her preface, she makes a strong and cogent plea for the importance of the latter, all the more impressive in coming from an accomplished performer at the ‘poetry gigs’ she defines as not enough to sustain long-term poetic effort:

The real tragedy of Australian poetry is not how few good poets there are, but how few books of poetry are bought and read. It is wonderful to see the crowds hanging from the rafters at poetry gigs and to hear the roar as favourite poets perform their work … But poets do not live by applause alone. Our best books demand and deserve the same support by publishers, book-sellers and readers that the alpha list of fiction and non-fiction takes for granted.

Indeed, it would be sad to see the poetry annals totally without recognition of the importance and quality of recent collections from poets as diversely accomplished as Les Murray, Jennifer Maiden, John Tranter or Laurie Duggan. Maiden’s ‘Foxfall’ poems were for me a highlight of Porter’s anthology – such scalpel-sharp, almost perversely beautiful images of distaste for ‘the sugars of ambition’, ‘the syntax of Gump’, ‘the whole / bushy new millennium, its malice, / its killer smile and phantom techno-shares’. A mastery of shifting registers is even more pronounced in Les Murray’s ‘The Nostril Songs’, an exuberant, bravura performance to delight those who will always be grateful for the way that Murray opened up a whole new territory of poetic idiom, structure and sensibility in poems such as ‘The Broad Bean Sermon’, ‘Sprawl’ or ‘Walking to the Cattle Place’.

Some thirty collections are listed in Porter’s acknowledgments. The selection and publishing schedule for the anthology means that a number of these date from the later part of 2005, and thanks to the same deferral process, anyone wanting a taste of one of the most striking 2006 collections, Robert Adamson’s luminous The Goldfinches of Baghdad, will have to wait for the 2007 anthologies. The number of publishers involved is not extensive, and it is alarming to see that seven collections come from Five Islands Press, the continued existence of which is in doubt thanks to the semi-retirement of its founder, Ron Pretty. The list drives home the debt of gratitude that we owe for Pretty’s readiness to foster new talent by taking on the commercial risks of first collections. That gratitude must expand exponentially when we see how many poems in each anthology were first published in Blue Dog, the biennial publication of the Poetry Australia Foundation, established and driven by Pretty’s commitment. The Foundation and Blue Dog are at least sure of survival under the aegis of a newly formed Australian Poetry Centre, made possible by generous sponsorship from the Copyright Agency Limited. The best possible Vale that poetry readers can give Pretty is to ensure that his work continues by joining the Foundation or subscribing to Blue Dog. No excuses: you can learn all about it on www.poetryaustraliafoundation.org.au.

Despite her enthusiasm for the current collections, a great deal of Porter’s material is drawn from the journals that are the lifeline of local poetry. An initial impression that she had cast her net more widely over these did not survive a cross-check. The list of journals consulted is much the same for both volumes. It is rather that Porter has trawled for a wider catch. This is, of course, partly a function of the generous number of poems allowed by the publisher. There is space for small poems by relative unknowns to catch the eye and give quiet pleasure. Two such face each other on pages forty-four and forty-five: James Charlton’s ‘Letter to Walt Whitman re: Iraq’ speaks unspeakable horror through the imaginative framing device of its power to silence one of modernity’s most loquacious poets. Aidan Coleman’s imagistic ‘Blue-Tongue’ diverts as it spins nine lines from an initial comic image of that aggressive-looking lizard as ‘Fat like a full tube / of toothpaste’. Porter does seem, however, to have a more omnivorous poetic appetite than Beveridge. More taste, perhaps, for apparent disconnections such as the magical aphorisms of Kevin Brophy’s ‘Sentences’, which begins: ‘After being away from my son for a day his size frightens me. / Always I am surprised by the bitterness of coffee.’ More sympathy, too, for unbowed warriors of the avant-garde such as Ken Bolton and joanne burns, or experimental departures such as Jordie Albiston’s play with internal line dividers in ‘Amoroso’:

the next morning | look | even the

poem is masculine now : mouthing out

metaphors one by one | tongue in my

ear | hand on my thigh! Arms astretch

in muscular lines | I am not inclined ||

It is tempting to allot ‘control’ as Beveridge’s primary criterion, and ‘energy’ as Porter’s. After all, Porter speaks, in her briefer preface, of ‘knuckle-raw’ poems among the ‘embarrassment of riches’ available for selection. That is not a phrase one imagines Beveridge using admiringly. But it is not so simple: poetry works on both energy and control, and the ratios shift about. Consider, for instance, the representation of Judith Bishop, one of the newer poets appearing in both anthologies. ‘Still Life with Cockles and Shells’ (winner of the 2006 ABR Poetry Prize) has marked affinities with Rosemary Dobson’s poetry, not only thematically in being based on a work of art, but also in the finely detailed, elegant poise of its language and structure. It is selected by Porter, while Beveridge chooses ‘Rabbit’, much more visceral in its evocation of urgent movement, the technical control of its long lines essential but inconspicuous:

Rabbit, winding up your stride, in your alignment, recalling full stretch,

a god’s arrow-head, shaft, lengthening from nose to tail, aching to occupy

the whole damn bubble of the moment of each movement …

Bishop, like West Australian Kevin Gillam, is that new breed of Australian poet: a graduate of a Creative Writing course (in Bishop’s case, from Washington University in St Louis). They are witnesses to the fact that such courses, if they cannot create natural talent, can give an intelligent awareness of ‘the craft so long to learn’ and an assurance that must otherwise be acquired, or destroyed, through the trial and error of haphazard publication. Still, they must depend in the end on publication to find their audience, and this is most likely to start with journals and anthologies such as these. I for one will now be watching for the forth coming first collection mentioned in Beveridge’s notes on contributors.

But it is not only ‘new’ poets who can come to our attention through such anthologies. Gillam’s name reminds us that anthologies can bridge those gaps of distance that feed the regionalism of much poetry publishing, in particular making some West Australian poets virtually unknown on the east coast, and vice versa. Judith Wright once argued that regionalism was needed to break up the nationalist/provincial dichotomy souring the pursuit of an ‘Australian’ poetic identity. In context, she had a point. Now, however, despite all the cant about the triumph of individualism, a pressure towards cultural centralism risks dismissing the outer regions of both place and ideas as provincial at best and ‘un-Australian’ at worst. We need to hear (and listen to) all the voices. Years ago, John Crowe Ransome wrote in ‘Philomela’ of the split consciousness making the romance of the nightingale’s song inaudible to ‘a bantering breed, sophistical and swarthy’. The irony was that his poem evoked both states, bringing them back into their endlessly uneasy yet complementary relationship, offering more than a truncated, amputated life. One reason why poetry matters is that it is supremely the art of holding contrarieties in a tensed whole; it is also the art of letting us see those contrarieties in their purest, most challenging, most playful, most melancholy selves.

Beveridge and Porter may be different kinds of poets, but they understand the commonweal of poetry, and their respective books serve it well. Each has attractions over and above the poems themselves. Those who like to have their poets placed in context will value Beveridge’s notes on contributors; others will be grateful for the different kind of context given by Porter’s opening section, honouring five poets lost to death in recent years. It is an ecumenical group: Bruce Beaver, Shelton Lea, Richard Deutch, Vera Newsome, Lisa Bellear. One possible downside of Porter’s eclecticism is that readers may reject some of her choices. While I would not wish away one of Beveridge’s poems, there are a couple of Porter’s I actively dislike – something in their rhetoric or attitude makes them, in Porter’s phrase, ‘deeply uncongenial’. I name no names. It is bad enough editing an anthology, knowing that necessary exclusions will give offence, or worse, deep hurt; a reviewer is even more constrained. With so many good poems not explicitly recognised, why waste space on rejections that, after all, bear the ‘stamp of my own sensibility and thoughts about certain approaches to writing’ (Beveridge). I would rather plead gratitude for the many unmentioned poems that made me laugh, sigh, reflect – and agree with the editors that Australian poetry is in mettle some condition.

Comments powered by CComment