- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Candour and ferocity

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

There is certainly a refreshing candour in My Story and a good deal of pleasant anecdote and humour, but, on the whole, not a lot of ferocity. Cosgrove is most at ease and most readable when he can be convincingly diffident, mocking his own pretensions or, more often, the embarrassing lack of them, as in his account of his arrival at Duntroon Military College. Just short of eighteen, with a ‘lot of growing up to do, both physically and emotionally’, coming off a modest performance in his second try at the Leaving Certificate, with a school track record of larrikin insouciance, the young Peter Cosgrove had every reason to feel nervous as he boarded the bus outside the Canberra station for the short trip to Duntroon. Finding he is sitting next to ‘a fellow who seemed about my age (although years more mature)’, Cosgrove decides to ‘break the ice’. As a result, he discovers that this young man is a product of one of Sydney’s most prestigious private schools, that he had been school captain, a senior cadet, captained the School XV and had been selected for the combined GPS rugby team. Despondently, Cosgrove asks about cricket, assessing himself as ‘no world beater [but] better [at cricket] than at rugby’. His delight in hearing that his companion never played the game is quickly snuffed out when the young man explains that, as stroke of the school eight when his school won the Head of the River, he had no time for cricket. ‘We sat in silence for a moment and then he turned to me and said, “What about you?” I said morosely, “I’m on the wrong bus!”’

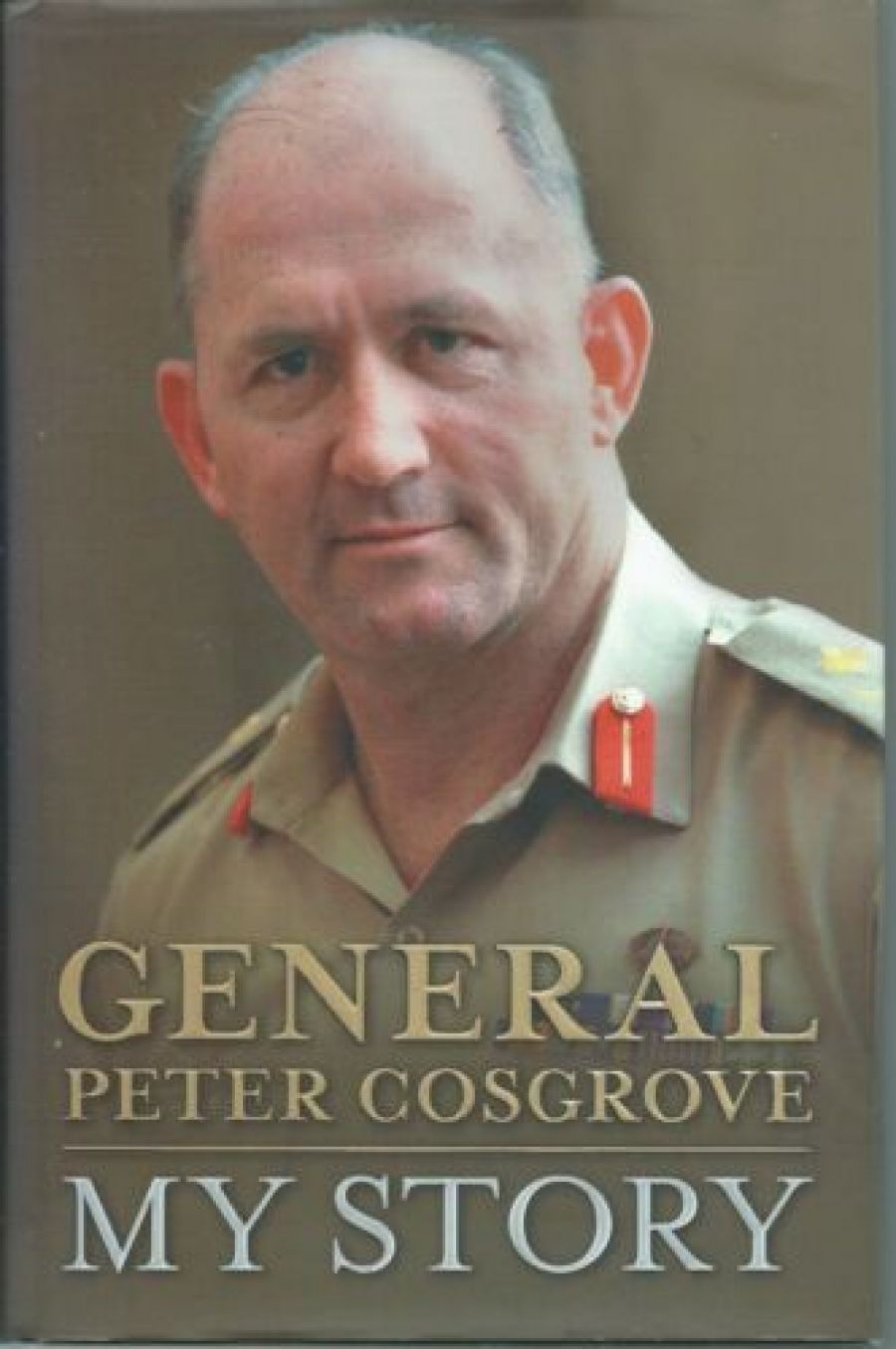

- Book 1 Title: General Peter Cosgrove

- Book 1 Subtitle: My Story

- Book 1 Biblio: HarperCollins, $49.95 hb, 468 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/x9jkrd

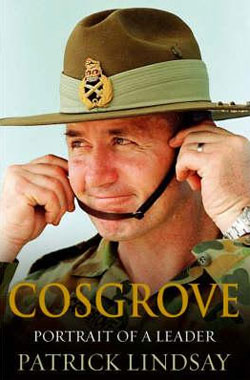

- Book 2 Title: Cosgrove

- Book 2 Subtitle: Portrait of a Leader

- Book 2 Biblio: Random House, $34.95 pb, 301 pp

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

There are many anecdotes like this one, nicely paced, engaging and sometimes with a resonance beyond the mere humour of the moment. In this case, Cosgrove had a number of reasons for worrying that he might indeed be on the wrong life bus, not up to Duntroon and its challenges, let alone those of the army itself, waiting for him beyond the college walls. That he did succeed – and brilliantly – becomes in his memoirs a narrative of apparent good luck, a few canny decisions and a considerable amount of personal fortitude and mental toughness. In other words, while never descending to false modesty, Cosgrove favours a species of Aussie and especially army understatement which is sometimes frustrating for a reader, making you feel that there is more to be said and that it might be more trenchantly said. There are other occasions when the account seems under such constraints of diplomatic obliquity that Cosgrove’s innate tendency to openness and a no-nonsense frankness has been stifled. It is at such points that Lindsay’s Cosgrove: Portrait of a Leader often provides an interesting counterpoint. To take one example: the so-called Collins affair.

In My Story, Cosgrove devotes a little over two pages to this ‘interesting aspect’ of his mission in East Timor, ‘the “switching off” of intelligence support to INTERFET for about twenty-four hours in December 1999’.

Lieutenant Colonel Lance Collins, Cosgrove’s senior intelligence officer, was hard-working, dedicated and efficient, but he had what Cosgrove saw as ‘a significant bee in his bonnet about the Defence Intelligence Organisation, Australia’s senior military intelligence agency in Canberra, and what he perceived to be their strong pro-Indonesian bias’. When one of the intelligence links to Australia was shut down without warning, Collins was convinced it was deliberate. Cosgrove enquired and accepted the explanation that it had been an unauthorised link, vulnerable to interception. As far as he was concerned, ‘that was the end of that apart from a request from the head of the Defence Intelligence Organisation (DIO) that our intelligence staff confine themselves to the immediate operating environment for INTERFET’. He takes this rebuke to be explicable as ‘a routine reminder of turf ownership’.

Lindsay devotes a nineteen-page chapter to the ‘curious story of what became known as the Collins affair [which] shadowed Cos during the last five years of his service’. A carefully researched treatment reveals the familiar story of failures of ‘recollection’ – an amnesiac affliction from which many government figures would suffer a catastrophic relapse during the AWB scandal – massive and inexplicable delays, such as the report of the Inspector-General of Intelligence and Security, Bill Blick, which took three years to complete and amounted to eleven pages, and the attempts by the Prime Minister’s Department and the Defence Department to solve their dilemma by ‘playing the man’. Lindsay refers to the ‘cynical methods that have characterised the Government’s approach to the entire affair’, and concludes:

Neither Cos nor Ric Smith [then Secretary of the Department of Defence] has ever corrected or retracted their earlier incorrect assertion that Collins was wrong and there was ‘no basis’ for his claim that the loss of access [to intelligence data via the link in question] was deliberate. Lance Collins is still waiting for a proper resolution of the affair. He and Martin Toohey [a Naval Lawyer and author of the major report on the matter], two respected and honourable men, have had their careers irreparably damaged and suffered overt and covert attempts at character assassination.

It is hard to reconcile this analysis with Cosgrove’s ‘impression of the whole issue … [as] somewhat low-key because in the end, during the operation in real terms, it caused barely a ripple’.

On the ‘children overboard’ affair, Cosgrove is more pointed. The initial report about adults holding children over the side was ‘incorrect’, and it ‘was obvious at lower levels of the chain of command that this particular act had not taken place’. He goes on to emphasise that ‘during the election campaign the initial erroneous report was never corrected’ and that the matter resolved itself into two key questions: first, had the navy acted unprofessionally, to which he answers, no. And second, problems with the chain of command, how information passed up and down the levels of responsibility, and what happened to it at the upper echelons. Choosing not to comment on the political dimension, he proposes and explains why ‘it wasn’t the ADF’s finest hour at more senior levels’, a reference in particular to the dogged intransigence of Admiral Chris Barrie in supporting the original lie.

Again, Lindsay’s account is tougher, more detailed and, it has to be said, more interesting: ‘Barrie did the honourable thing and owned up in the end. The government didn’t and hasn’t. For Cos it was a timely warning of the mine-fields ahead.’

But this is where an intuitive liking for, and trust in, Cosgrove kicks in. I don’t for one minute think he’s trying to mislead or cover up. He is an army man through and through, and for a good deal of his career a senior and important one. It will take a great deal to convince Cosgrove that members of the defence forces are not the fine and responsible people he expects them to be, regardless of the dangers inherent in institutional rigidity of the kind espoused by the military. Respect for institutionalism, for highly ranked professional and political superiors, is as much ingrained as is the unquestioning attitude to orders. Nothing in the military would work otherwise, especially in emergencies. Where an order ceases to be an order and becomes the basis for discussion – as, for example, in academe – the name of action is lost, ‘sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought’. Likewise, where rank and position become open to question and not the focus of unqualified respect, chaos ensues.

These attitudes and acceptances are hard-wired, as they say, in Cosgrove’s personal and professional self, yet the institutional man does not blur the human being. Cosgrove has good things to say about people and tempers his criticisms when he has to make them, because he is a decent bloke – the kind you take to in that Orwellian manner. It is obvious, for example, that his wife, Lynne, is a splendid woman, but you wish he’d report just once that she threw a tantrum, or that the place was a shambles when he arrived home from overseas. This natural inclination to be positive is understandable in references to his wife, but it gives a slightly unreal tinge now and then to his descriptions of his comrades in arms and of some politicians. But upbeat straight forwardness is his strength and his mode and, while he could have done with more stringent editorial help, the story is in general competently managed.

Nevertheless, General Peter Cosgrove: My story actually needs to be complemented by the less easily impressed, forensic instincts of Patrick Lindsay who, while a wholehearted admirer of ‘Cos’ and succumbing in his turn to the blandness that threatens the narrative of such a decent man, offsets Cosgrove’s diffidence with revealing detail and shakes up the army man’s ordained view of the world with the rough subversion of biographical enquiry, creative scepticism and an unequivocal quality of research.

Comments powered by CComment