- Free Article: No

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Stephen Kelen’s new book is an ambitious, wide and free-ranging journey through past and present, war and peace, family life, travel and technology. It has all the hallmarks of Kelen’s previous books: a marvellous ear and restless eye, a gift for narrative that challenges as much as it reaffirms, and a willingness to tackle anything that takes his attention. These (mostly) narrative poems have a relaxed, conversational style, even when Kelen’s subject matter is bleak and charged with menace: ‘The gun going off / made us laugh till even our / humanity couldn’t give a shit // The police came and went / and we thought about that’ (‘Deadheads’). This relaxed, colloquial style is at the heart of much of the book, and the opening poem, ‘A City’, works as a short, lyrical template for what is to come: rural, urban, celestial, domestic, political, technological. Kelen works a spell and places them all into fourteen lines. It is a tight, promising beginning.

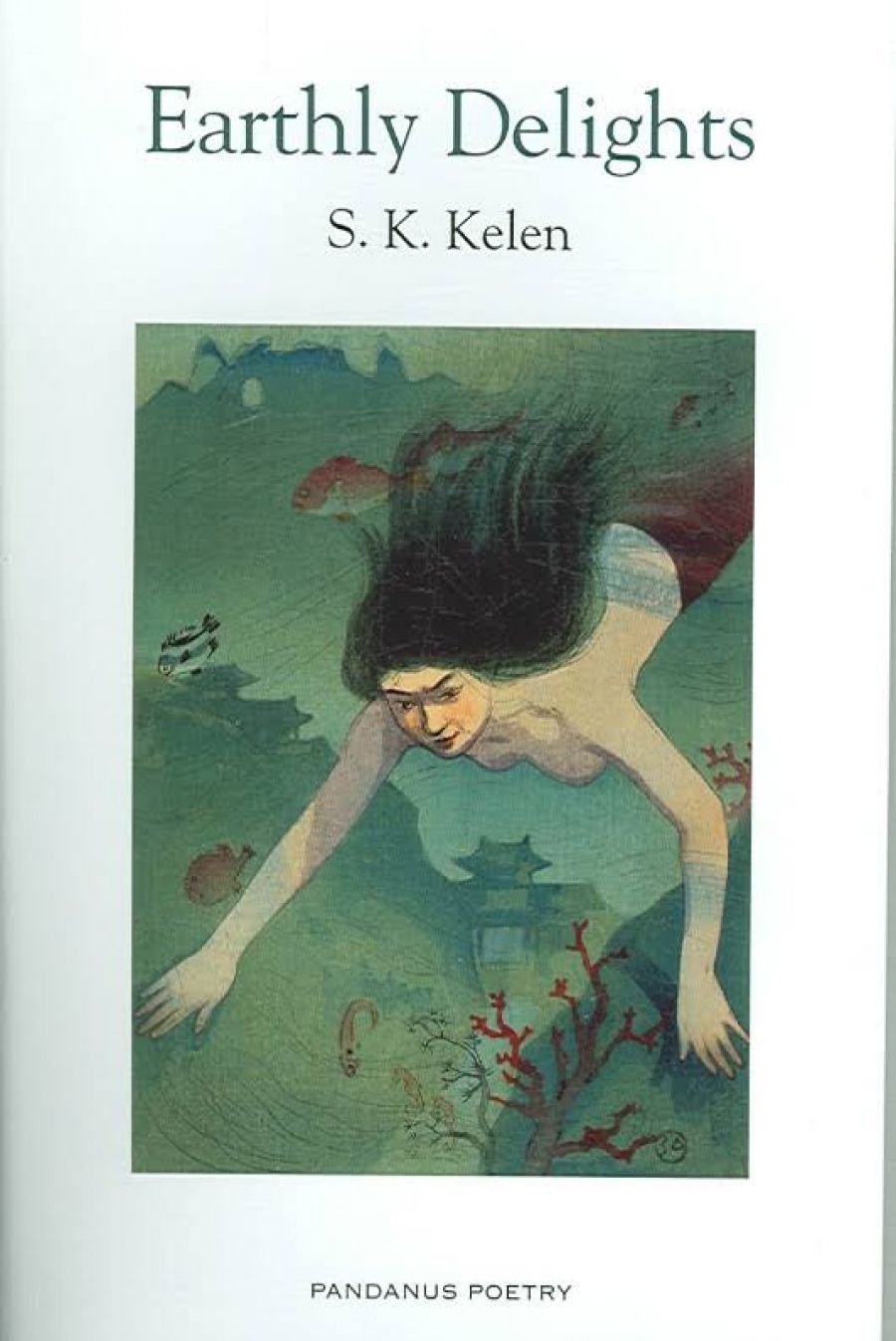

- Book 1 Title: Earthly Delights

- Book 1 Biblio: Pandanus, $19.80 pb, 108 pp

The second poem, ‘Bon Voyage’, is a moving farewell to his father. Kelen is a difficult poet to pin down, stylistically – constantly on the move, working to lay open whatever amazes or concerns him. From the rural/urban setting of an elegy, we head straight into an alignment of World War I machinery and hands-on death with Yeats’s pasture songs. ‘Slouching’, in two parts – ‘Early Twentieth Century’ and ‘End of That Century’ – brilliantly contrasts two worlds: one idyllic, against a background of personal brutality, the other unfolding on a computer screen, where ‘A pixellated harmony would bring peace at last. / Too late for the dead oceans and species expired / the children killed by smart or stupid bombs.’ It ends with ‘Yeats’ poems / are downloadable (with expert commentary)’.

‘Hanoi Girls’, one of my favourite poems, reveals Kelen’s understanding of how taking a peripheral stance to subject matter can mine its seam and offer the reader a shock of surprise and delight. The central image is of young, stylish women on motor scooters, riding and stopping to chat at the lights. As they weave in and out of the heavy traffic, Kelen weaves a short history of wealth, poverty, war and peace, in this ‘most sensible of cities’.

Kelen’s travels, and his ability to capture his observations in poetry that is deeply nuanced and conversational, have served him well. When he writes about roughing it in India, a Shanghai sweatshop, teenagers or cannabis, he can be captivating and profoundly moving. Michael Brennan has written that Kelen’s poetry ‘is first and foremost a communicative act’, and that ‘his lyricism is rich with allusion and dislocation’. Brennan is right: Kelen’s poetry often reads like the transcript of an intimate conversation, and his poems are rich with allusion and dislocation. For me, it is this aspect that I find most troubling. Poem after poem begins with so much promise, but more often than not they end without having moved on from a prescriptive show-and-tell exercise, where the subject matter is the central, identifying spark, and the poem’s full potential has not been reached. ‘Personality’ is a good example of this. The poem is about cars and the fact that they differ despite having rolled off the same production line. Kelen may have intended to draw an analogy with humankind, but if so it doesn’t work. There was so much potential for development here, for extensions of metaphor, for introducing conflicting, external ideas that can deepen and enrich a central theme. For me, the best poems work this way. A poem about cars can be a fine thing, but a poem about cars that takes risks and sets ideas against each other, while retaining a unifying thread, can be marvellous.

‘System Arrest’ is another poem that suffers from a concentrated, subject-driven narrative. The poem is about pollution in the Coral Sea and how it affects the marine life. So far, so good. Kelen’s list and commentary is to be celebrated, in that his descriptions and general detail paint a bleak environmental picture. But I wanted more. More of what? Some curious, subtextual development, something to, as Les Murray has said: ‘Make me stop and ask, “Now why did the poet do that?”.’ I wanted Kelen to use his abundant lyrical and narrative gifts to surprise me.

Despite these reservations, Earthly Delights is a fine book. Kelen’s imagination is never at rest, and I admire his passion and refusal to turn away from difficult material. Al most all these poems have something truly fine inside them. Kelen never attempts to make it easy for the reader, to give comfort in the face of political or domestic horror, but nor does he write gratuitously. Chaos breaks through, or can be seen hammering at the edges of many of these poems, and Kelen deals with it head-on. There is real humour here, too. ‘Life’s pleasingly shabby, charmingly Dickensian / with a genteel take on poverty, don’t let reality spoil / a good memory’ (‘When Past and Future Meet’). ‘Ode to Agent Eighty Six’ is the perfect vehicle in which to tackle the bumbling Maxwell Smart.

‘Firebirds’ is the most difficult, yet rewarding poem in this book. Kelen is at his finest here, moving in and out of frame, dovetailing reality with pure abstraction, and all the while offering us his unique, edgy take on a world that seems ready to unravel at any minute. It is the kind of poem that returns me to his work, where emphasis has been deflected from the intellectual to the mysterious and the sensual. The best of this book can be seen as a close-ordering of the senses, breaking open into a visual and aural feast.

Comments powered by CComment