- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Custom Article Title: Peter Menkhorst reviews 'Starvation in a Land of Plenty' by Michael Cathcart

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Three pale strangers

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The white explorers who first penetrated the interior of this continent were exceptional men. White Australians of the time considered them heroes, performing an essential role in identifying opportunities for exploitation, settlement, and commerce. Mostly, the explorers were heroic – determined, tough, single-minded, and stoic in the face of enormous hardship. They also needed bushcraft, that elusive ability to ‘read’ the landscape, the weather, vegetation communities, and animal behaviour, so as to improve the quality of the daily judgements needed for survival. Success under these conditions requires a clear vision and a strong, intelligent, and organised leader. John McDouall Stuart and Augustus Gregory come to mind as examples; Robert O’Hara Burke does not.

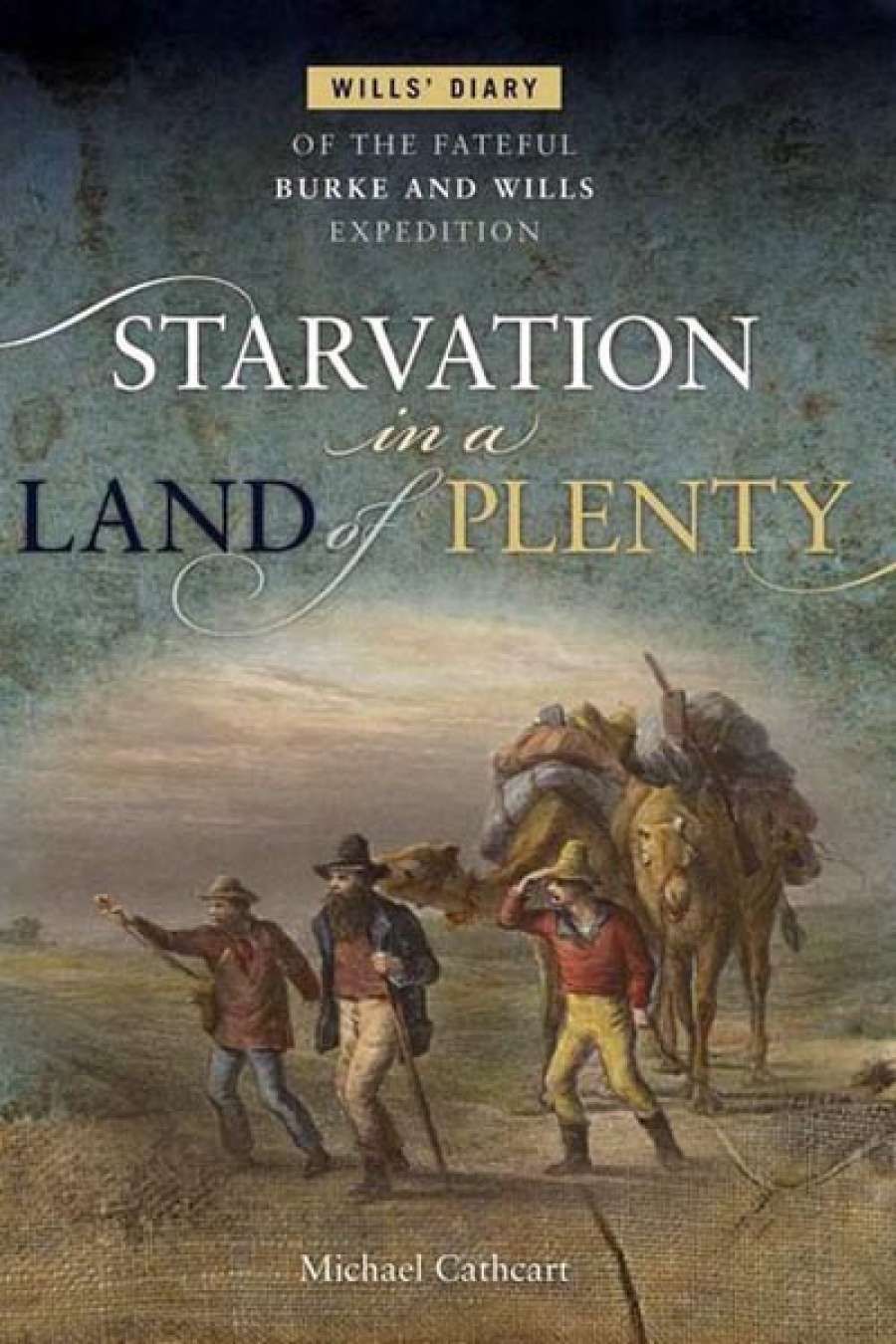

- Book 1 Title: Starvation in a Land of Plenty

- Book 1 Subtitle: Wills’ diary of the fateful Burke and Wills expedition

- Book 1 Biblio: National Library of Australia, $39.99 pb, 213 pp

For all that has been written about the demise of the Victorian Exploring Expedition, there is actually little firsthand evidence of what took place. Burke kept no journal. Thankfully, the expedition’s surveyor and second in command, William Wills, was an exemplary scientist and team member. He carried out his duties diligently, despite terrible deprivations. His detailed records and charts showing his navigational computations have survived and have allowed the precise route and the location of the expedition’s campsites to be recently determined.

However, it is the diary kept by Wills for the final eleven weeks of his life that provides the personal and intimate detail unavailable elsewhere. Now held in the National Library of Australia, Wills’s diary is a lucid account of the tragedy that unfolded between April and June 1861 after the remnants of the expedition had returned, in a pitiful state, to what should have been their safe haven beside Cooper’s Creek, near present-day Innamincka. It includes a trove of insights into Wills’s thoughts as the dreadful realisation dawns that he will probably die at this lonely water-hole hundreds of kilometres from the nearest Europeans. It is these insights that Cathcart mines so successfully in this book, including Wills’s evolving attitudes towards the local Aboriginal people, the Yandruwandha, his relationships with Burke and King, and his resolutely scientific view of the world, including his rejection of religion. Wills shows himself to be a man of the Enlightenment, dedicated to careful field observation of natural phenomena, in contrast to Burke, who seems to have been most interested in personal glory. It reinforces the central role of Wills in the expedition’s success – they did after all cross the huge blank space on the map. Wills is the real hero in this story.

Arrival of Burke, Wills and King at the deserted camp at Cooper’s Creek, Sunday evening, 21st April 1861 (1907) by John Longstaff (National Gallery of Victoria)

Arrival of Burke, Wills and King at the deserted camp at Cooper’s Creek, Sunday evening, 21st April 1861 (1907) by John Longstaff (National Gallery of Victoria)

Michael Cathcart joins a growing list of historians to have examined and interpreted Wills’s diary. The first was Wills’s grieving father, who published edited extracts of his son’s diaries and letters, with commentary, in 1863. Frank Clune published Dig: A Drama of Central Australia in 1937, Alan Moorehead marked the centenary of the expedition with Cooper’s Creek (1963), and, more recently, Tim Bonyhady (Burke and Wills: From Melbourne to Myth, 1991) and Sarah Murgatroyd (The Dig Tree, 2002) have produced acclaimed accounts of the expedition and its place in Australian history. These were joined by a fictional account by Alan Attwood, who focused on the survivor, John King (Burke’s Soldier, 2003). The sesquicentenary of the expedition in 2011 prompted a scholarly examination of the previously ignored scientific output (Joyce and McCann, Burke & Wills: The Scientific Legacy of the Victorian Exploring Expedition, 2011). Among numerous other findings, this analysis convincingly scotched the notion that Wills was a poor navigator, and demonstrated the contribution of the forgotten members of the expedition, notably the scientists Ludwig Becker and Hermann Beckler. Given this level of literary attention, do we need another book about Burke and Wills?

Robert O'Hara Burke by William Strutt (1825-1915)

Robert O'Hara Burke by William Strutt (1825-1915)

Cathcart’s approach of concentrating on the persona of Wills, as reflected in his diary, sets this work apart. So do the numerous, carefully selected illustrations, which convey the social and ecological settings. We receive a sympathetic view of Wills as a loyal lieutenant to the end, despite Burke’s record of poor decisions. Only in the last days does Wills make some pointed comments in his diary that could be taken as criticism. Cathcart also highlights Wills’s matter-of-fact, indeed scientific, attitude to his impending death, including Wills’s strangely compelling descriptions of his failing health and the symptoms of slow starvation.

Photographic reproductions of key sections from Wills’s diary highlight his neat handwriting and confident prose, even as he is dying, indicative of his unfailing strength of mind.

One theme, laboured in the title, with which I do not concur, is that Burke, Wills, and King ought to have been able to survive their eleven-week ordeal at Cooper’s Creek because the area was a ‘land of plenty’. It is easy to underestimate the skill and knowledge required to live off the land in such country, especially when the three were in a deplorable state of health to begin with. Their prolonged exposure to a nutritionally inadequate diet and insufficient hydration on their trek to the Gulf and back deprived them of any hope of quickly regaining rude health. King, the sole survivor, never regained good health and died a little over ten years later at the age of thirty-one. The local Yandruwandha people lived reasonably comfortably, but they were experts, backed by thousands of years of experience, and were locally nomadic, their movements likely driven by food availability. The three pale strangers in their midst were in no state to travel with them, or even to survive on their diet.

Comments powered by CComment